Abstract

The main aim of this study was to assess the overseas travel motivations and market segmentation for the elderly. The study focused on the tourism sector of Thailand. The study explored various factors that motivated elderly tourists to travel, in line with the main objective. The study explored elaborately the various forms of economic impact analysis with regard to inbound tourism. The study relied on primary data using structured questions to explain the main objective and the data was analyzed using statistical tools like SPSS, and ANOVA analysis.

The study found out that the top three travel motivation factors for the elderly tourists were: rest and relaxation; visits to new places; and learning and experiencing new things. This is indicated by the values of their means as 4.13, 3.97, and 3.96 respectively. In addition, the study found out that the bottom three travel motivation factors that least motivated the elderly tourists were: seeking intellectual enrichment (mean = 3.48); exercise physically (mean = 3.10); and visit family and friends (mean = 2.98).

The results further indicate that the most satisfying travel requirement that was considered by the elderly tourists was the safety of the destination (mean = 4.10). Location of accommodation and natural attraction followed in that order with means of 4.09 and 4.05 respectively. Consequently, the results further indicate that the least important travel requirements that were considered by the elderly tourists were: hotel accessibility and disability features (mean = 3.69); special events and festivals (mean = 3.68); and leisure activities (mean = 3.52).

The findings of this study are very relevant to elderly tourists, tourist planners, and tourist marketers. It is also adequate for the country to improve and protect the physical appearance of tourist destination sites to enable her to be in a competitive position as compared to the other countries. Moreover, the ease of accessibility to the tourist destination sites should be improved to give an easy time for the elderly tourists to move around. Accommodation facilities and other social amenities should be upgraded so that they can be up to standard and fit the specifications and the requirements of the elderly tourists.

Introduction

Overview

This chapter covers the background to the study, problem statement, research objectives and hypotheses and the significance of the study.

Background to the study

The population of the elderly people in the world has grown rapidly as a result of positive changes in the health sector and improvement of life expectancy age. 11% of the total population in the world was aged at least 60 years at the beginning of the 21st century; it is postulated that the percentage will rise to 20% by the year 2050 (Hall, 2006, p. 15).

In less than 20 years, it is estimated that one third of both Japan’s population and Germany’s population will be at least 60 years of age. In the same way, at least a quarter of France’s population, the UK’s population, and Korea’s population will be at least 60 years of age (Dann, 2001, p. 239).

The tourism industry all over the world has developed a keen interest on the growing elderly population as a result of its large size, high purchasing power and more time to commit to travel because they have retired. The elderly people normally have accumulated income or a good pension, thus, they can comfortably pay up the expenses involved in travelling (You & O’Leary, 1999, p. 23; Bai et al., 2001, p. 152).

The elderly population is highly motivated to take part in leisure activities (for instance, long distance travels) due to the fact that many of them are well educated, have a good income and a good health status (Sellick & Muller, 2004, p. 170).

In addition, the elderly tourists have a lot of free time after retirement, thus, making them to be more captivating to the business of tourism that has a varied demand every season (Jang & Wu, 2006, p. 310). Many scholars have pointed out that the elderly market is very important to tourism industry as they are one of the highest consumers (Shoemaker, 2000, p. 15; Bai et al., 2001, p. 148; Horneman et al., 2002, p. 24; Jang & Wu, 2006, p. 308).

Motivation refers to the category of a need or a plight that urges a person to engage in a certain action that is expected to offer him/her satisfaction (Moutinho, 2000, p. 13). In other instances, motivation has been taken to mean the drive that exists within a person that compels him/her to do a certain thing so as to meet a psychological need or a biological need (Fridgen, 1996, p. 46). Travel motivation is the kind of motivation that is connected to the reason why people decide to travel (Hsu & Huang, 2008, p. 52).

The motivation that is connected to the tourists’ travel encompasses a wide spectrum of the tourists’ behaviors and their previous travel experiences. Examples of motivations that lead people to travel include: the desire to relax, the urge to gain excitement, the need to interact with friends socially, the spirit of adventure, the urge to interact with families, the drive to improve personal status, and the urge to get away from the daily routines or stress.

Motivation is a procedure concerning preferences made by individuals or subordinate organisms among substitute forms of deliberate activity (Britton, et al., 1999, p.27). Barcelo (2000) suggested that “the present and immediate influence on the vigor, direction and persistence of action can be termed as motivation” (p. 24).

Kinni (1994) found out that “business managers are striving to establish and maintain an atmosphere that is more favorable for the satisfaction of tourists, who are striving together in groups towards attaining of pre-determined goals” (p. 14). In the same way, Robson (2002) insinuated that “motivation can be offered to workers as per the following methodologies: the customary or traditional approach; implicit bargaining; human relations approach; internalized motivation; and competition” (p. 62).

Statement of the problem

Thailand is one of the leading tourist destinations in South East Asia because it has a diverse nature, rich and diverse culture, and also friendly people. The tourism industry for Thailand has grown over the years in spite of a minor decline in 2009 as a result of various internal and external shocks.

International tourism arrivals grew by 2% in the year 2011 as their number reached 17.3 million; in addition, in the same year (2011) Thailand received more than $15.5 million from tourism (Hall, 2006, p. 15). The income from tourism contributed to more than 14.1% of Thailand’s GDP. Moreover, Thailand’s tourism industry has created more than 3.9 million jobs (Hall, 2006, p. 15).

Many elderly tourists are motivated to travel due to the fact that they have retired from their jobs and have much time to commit to travelling around. In addition, they have an accumulation of lifetime income savings and pension, which increases their purchasing power. Elderly tourists always pay attention to some important factors before they make their travel. They have to make sure that the travel destination will guarantee them their security or safety. More so, they also check on the accommodation facilities and other social amenities to make sure that their comfort is guaranteed.

Objectives of the study

The general objective of this study was to determine the oversea travel motivation and market segmentation for the elderly. In line with the general objective, the study examined the following specific objectives:

- To determine the effectiveness of rest and relaxation on travel motivations for the elderly;

- To determine the influence of the desire to visit new places on travel motivations for the elderly;

- To determine the influence of the urge to learn and experience new things on travel motivations for the elderly;

- To investigate the influence of the urge to get away from stress on travel motivations for the elderly;

- To investigate the influence of the desire to escape from the day-to-day activities on travel motivations for the elderly;

- To determine the relevance of safety of the destination on travel motivations for the elderly;

- To determine the relevance of location of accommodation on travel motivations for the elderly;

- To determine the influence of natural attractions on travel motivations for the elderly;

- To determine the influence of availability of medical facilities on travel motivations for the elderly;

- To determine the influence of historical attractions on travel motivations for the elderly;

- To determine the influence of cultural attractions on travel motivations for the elderly.

Hypotheses of the study

In order to meet the above objectives, the following hypotheses were tested:

- Ho1: The desire for rest and relaxation motivate the elderly tourists to travel;

- Ho2: The desire to visit new places motivate the elderly tourists to travel;

- Ho3: The urge to learn and experience new things motivate the elderly tourists to travel;

- Ho4: The urge to get away from stress motivate the elderly tourists to travel;

- Ho5: The desire to escape from day-to-day activities motivate the elderly tourists to travel;

- Ho6: Safety of the destination motivate the elderly tourists to travel;

- Ho7: Location of accommodation motivate the elderly tourists to travel;

- Ho8: Natural attractions motivate the elderly tourists to travel;

- Ho9: Availability of medical facilities motivate the elderly tourists to travel;

- Ho10: Historical attractions motivate the elderly tourists to travel;

- Ho11: Cultural attractions motivate the elderly tourists to travel.

Justification of the Study

The findings of this study are of great value to policy makers and regulatory authorities. It provides the policy makers with a wide exposure with regard to the assessment of travel motivations and market segmentation for the elderly, thus enabling them to adopt the relevant strategies in line with the situation. The findings of this study also add to the body of knowledge of related studies about the assessment of oversea travel motivations and market segmentation for the elderly.

Scope of the Study

The scope of this study was in line with the general objective, which was to explore on the oversea travel motivations and market segmentation for the elderly. Using primary data and applying statistical techniques, the study explained the variables to meet the research objectives. The study used a cross-sectional research design to meet the objectives. The data of the survey were analyzed using statistical techniques such as SPSS and ANOVA analysis.

Literature Review

Introduction

This chapter reviews the theories both empirical and theoretical that are closely linked to the oversea travel motivations and market segmentation for the elderly.

Seniors’ travel motivations

Motivation refers to the category of a need or a plight that urges a person to engage in a certain action that is expected to offer him/her satisfaction (Moutinho, 2000, p. 13). In other instances, motivation has been taken to mean the drive that exists within a person that compels him/her to do a certain thing so as to meet a psychological need or a biological need (Fridgen, 1996, p. 46). Travel motivation is the kind of motivation that is connected to the reason why people decide to travel (Hsu & Huang, 2008, p. 52).

The motivation that is connected to the tourists’ travel encompasses a wide spectrum of the tourists’ behaviors and their previous travel experiences. Examples of motivations that lead people to travel include: the desire to relax, the urge to gain excitement, the need to interact with friends socially, the spirit of adventure, the urge to interact with families, the drive to improve personal status, and the urge to get away from the daily routines or stress.

Pearce (1982) connected tourists’ motivation and behavior to the Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs; he was of the opinion that “the main reason that made the tourists to be attracted to the destined place of visit was their desire to attain self actualization, the feeling of love or belongingness, and also to attain the physiological needs” (p. 42).

There exist various available literatures that explain the various factors that motivate tourists to travel. In their study, Cleaver et al. (1999) revealed that “the market for the elderly is not uniform, and they pointed out seven segments that relate to the motivation for the elderly tourists.

The segments include: thinkers, nostalgic, physicals, learners, status seekers, friendly and escapists” (p. 8). In addition, Backman et al. (1999) pointed out the similarities and contrasts that exist between the younger elders (55 to 64 years) and the older elders (65 years and above). In their study, they revealed that “the main motivation factors that drove the younger elders to travel was the need to relax or to engage in leisure activities; on the other hand, the older elders were mainly motivated to travel by educational attractions and national attractions” (p. 17).

Moreover, Fleischer and Pizam (2002) did a review of the past studies regarding travel motion and made an inference that “the older elders were generally motivated to travel by the desire to relax, interact, learn, and to gain excitement” (p. 108). In the same manner, Horneman et al. (2002) in his study revealed that “the motivation for the elderly was moving towards the desire to rest or relax, the desire for physical exercise or fitness, and the desire for education” (p. 34).

The most recent study done by Huang and Tsai (2003) did a review of the previous studies concerning travel motivation and found out that “the motivation to travel can be categorized into various groups, for instance, rest and relaxation, education, adventure, socializing, and escape from daily patterns of life” (p. 565). In the same way, Jang and Wu (2006) concluded that “the significant push and pull motivations of the tourists were: the desire to seek knowledge, and the urge to be safe” (p. 308).

Elderly tourist profiles and requirements

An exploration of the past studies concerning travel motivation factors mainly focused on senior or elderly travelers by checking on their profiles, tastes and needs. A study conducted by Anderson and Langmeyer (1982) to assess the profiles of the senior travelers mainly concentrated on two elderly groups (over 50 years and below 50 years).

The study found out that “both the two groups were motivated to travel by the desire to fulfill their pleasure, the desire to rest or relax, and the desire to meet families or friends; however, the group which was above 50 years of age had a higher probability of touring historical sites” (p. 22).

In addition, a study conducted by Javalgi et al. (1992) confirmed that “younger tourists are more educated as compared to the elderly tourists, thus, they always carry out an information search before they proceed with their visit” (p. 16). In addition, the study also found out that “the elderly tourists had adopted a culture of purchasing trip packages that covered the costs of both transportation and accommodation” (p. 17).

Zimmer et al. (1995) conducted a study that mainly dwelt on the attributes of the elderly travelers; the study found out that “the most crucial discriminating variables that existed between those who travel and those who do not travel were: mobility problems, age, and level of education” (p. 8). A study conducted by Koss (1994) found out that “the elderly tourists preferred tourism packages that offered them excitements and added value to their lives” (p. 37).

In a related study, Bai et al. (2001) conducted a study that focused on elderly tourists from Britain, Germany and Japan. They found out that “the elderly tourists preferred to have packaged tours; this was evident by the significant number of the tourists in travel parties” (p. 152). When the elderly tourists travel, they always choose credible tour operators who have a good reputation. They also make sure that their health will not be at any risk, and that their trip will give them the desired satisfaction (Hsu, 2001, p. 64).

The decision of the elderly tourists to prefer motor coach tours is influenced by their demographic characteristics, psychological characteristics and psychographic characteristics (Shoemaker, 2000, p. 18). Consequently, Lindqvist and Bjork (2000) found out that: “before the elderly tourists make a decision to travel, they always check on whether their safety is safeguarded; the desire for safety increases as the tourists grow older” (p. 153).

Behavioral patterns of the elderly tourists

Several studies have been carried out to check on the patterns of behavior of the elderly tourists. In his study, Shoemaker (1989) concentrated on elderly tourists from Pennsylvania by exploring their travel behaviors and their motivations to travel. He further “segmented the market for the elderly tourists into three groups, for instance, tourists travelling as a family, tourists who rested actively, and the older set of tourists” (p. 18).

Romsa and Blenman (1989) conducted a study that focused on the patterns of vacation for elderly German tourists by concentrating on their travel modes, travel destination, length of stay, type of accommodation chosen, and vacation memories. The found out that “all the above listed factors were instrumental in influencing the tourists to travel” (p. 182).

Another study conducted by Huang and Tsai (2003) on the elderly tourists from Taiwan revealed that “the elderly tourists were reluctant to sign up for an all-inclusive tour package” (p. 565). Instead, the elderly tourists preferred to have elegant tours which had a high quality in terms of provision of services. Littrell (2004) conducted a study that sought to explore on the tourism activities of the elderly tourists and their behavior when it comes to shopping.

The tourists’ travel activities that were explored in this study included sports tourism, cultural tourism, outdoor tourism and entertainment tourism. The study found out that “the profiles of the tourists were diverse with regard to their probability to shop at retail outlets, their choice of shopping malls, and their sources of information concerning the available shopping activities” (p. 351).

Motivation is regarded as a shape of the state of needs that influences a person to engage in a certain action or activity that has a higher probability of granting him/her a certain level of desired satisfaction (Moutinho, 2000, p. 13). Motivation is a procedure concerning preferences made by individuals or subordinate organisms among substitute forms of deliberate activity (Britton, et al., 1999, p.27). Barcelo (2000) suggested that “the present and immediate influence on the vigor, direction and persistence of action can be termed as motivation” (p. 24).

Kinni (1994) found out that “business managers are striving to establish and maintain an atmosphere that is more favorable for the satisfaction of tourists, who are striving together in groups towards attaining of pre-determined goals” (p. 14). In the same way, Robson (2002) insinuated that “motivation can be offered to workers as per the following methodologies: the customary or traditional approach; implicit bargaining; human relations approach; internalized motivation; and competition” (p. 62).

Travel motivation can be explained as the magnitude of commitment, vigor, and originality in the part of the tourist. For many tour managers, amidst of ever gradually increasing more aggressive business atmosphere of the recent years, finding out, means to motivate the clients. In reality, a variety of varied hypotheses and means of tourist motivation have appeared, extending from increased involvement to monetary incentives and employee empowerment.

For small tourist enterprises, motivation can occasionally be predominantly challenging where the promoters have frequently worked for many years for establishing a company that he may be reluctant to delegate significant authorities to others. But the business owners should be aware of such drawbacks. Some of the issues connected to unmotivated travelers include deteriorating morale, less contentment, and widespread dissuasion. If permitted to prolong, these issues can lessen earnings, competitiveness, and productivity especially for small business (Crouch & Jordan, 2004, p. 120; Crompton & Ankomah, 1993, p. 466).

The motivation theories can be linked to the psychological factors like: wants, desires and goals, as the theories provide a description of the psychological factors (Fodness, 1994, p. 563). The psychological factors of needs, desires or goals induce an urgent urge in the person’s mind which leads him/her to purchase goods or services; thus, motivation directly influences the feelings of the individuals (Gartner, 1993, p. 200; Dann, 1996, p. 43; Baloglu, 1997, p. 226). Consumers who have divergent motives may assess a tourist destination in the same manner especially if they are of the opinion that the destination provides them with the maximum utility.

The important motivational elements that have been pointed out by different scholars in their studies include: the urge to get away from the daily programs or work; and the urge to seek for alternative enjoyable experiences (McCabe, 2000, p. 1050). The push-pull model was generated by Crompton (1979).

The model postulates that “tourism is driven by two main forces; the first force, known as push, pushes the tourist out of his/her home driven by the desire to travel to an unspecified destination” (p. 410). In this context, the motivation of the push force depend on the satisfaction anticipated by the consumer, the urge to adventure, prestige, knowledge, and the desire to make new friendships. The second force, known as pull, provides the consumer with the direction regarding the choice of the destination (Uysal, Mclellan & Syrakaya, 1996, p. 62).

The motives of the pull force influence the consumer’s choice of the place to visit; the forces are connected to the features of the destination and the infrastructures that define tourism. The features of the destination enable the consumer to make judgments as to whether their desires will be fully satisfied (Mohsin & Ryan, 2003, p. 117; Beerli & Martin, 2004, p. 670; Uysal, Mclellan & Syrakaya, 1996, p. 62; Fodness, 1994, p. 563). When the consumer has already pointed out the need, he/she proceeds to identify the destination that grants him/her the maximum satisfaction.

It is very beneficial for the elderly consumers to learn about the travel destination before making up their minds to travel. A study conducted by Guy, Curtis and Crotts (1990) confirm that the consumers’ learning about a destination is determined by their previous experiences or by the kind of information that they receive either directly or indirectly concerning the destination. Consumers who are uncertain normally rely on information from travel agencies so that they can be equipped with the necessary information concerning the destination site (Money & Crotts, 2003, p. 195).

The search for information relating to the destined visit site by the consumers is motivated by the various contingencies in the market place and the nature of the visits (Fodness & Murray, 1997, p. 506). Consumers who travel on a regular basis have a more affinity to receive information that relate to the travel product or the travel destination; with this regard they are more enthusiastic to spread the information to other interested travelers (Jamrozy, Backman & Backman, 1996, p. 912).

The elderly tourists have different perceptions concerning the kind of travel destination that they wish to have. Perception refers to the way in which the travel consumers regard the value of the product (Sheth, Newman & Gross, 1991, p. 163; Correia & Crouch, 2004; Correia, Valle & Moço, 2005).

The concept of perception stems from the cognitive point of view or from the behavioral point of view. Thus, it should be noted that perception occurs as a result of the process of consumer learning together with their motivations. Previous researches concerning tourist motivation reveal that the consumers’ selection and assessment of travel products are influenced majorly by affective factors (Fodness, 1994, p. 558).

Every tourist is driven by his/her personal motivational factors to travel; these motivational factors are both internal and external and they define the tourists’ insights regarding the destination (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999, p. 870; Gartner, 1993, p. 193; Correia, Valle & Moço, 2005). The internal motivational factors stem from the push motives while the external motivational factors stem from the pull motives. Perception is a dynamic process due to the fact that the consumers have the ability to select, to organize and to spell out the various stimuli into a useful and clear manner.

The perception of the consumer, therefore, varies from the real characteristics of a product to the manner in which the consumer grasps and analyzes information (Dann, 1981, p. 190; Pearce, 1982, p. 153). Perception can occur selectively if the consumer decides to be selective in his/her exposure, attention, perceptual blockage and perceptual defense. It is a common practice of the consumers to select only things they need and block out the things that they regard as unnecessary or unfavorable to them.

There are two concepts of perception that stem from the tourists’ learning process. One of the concepts is the cognitive perception, while the other one is the emotional perception. When the elderly tourist assesses the features of the desired destination, cognitive perception is achieved; on the other hand, emotional perception relies on the thoughts of the consumer with regard to the desired destination (Gnoth, 1997, p. 292). Both the two perceptions (cognitive and emotional) are essential for formulating models of perception of the tourists’ travel products.

Every tourist has a great desire to satisfy his/her motivation when they decide to travel. Each tourist has a different interpretation of the concept of satisfaction, thus, its definition is divergent among the various consumers. Many scholars in their research articles have linked the definition of satisfaction to the distinction between expectation and experience (Woodside, Frey & Daly, 1989, p. 12).

Bultena and Klessig (1969) gave a definition of satisfactory experience as “a part of the level of the correspondence between the consumers’ desires and the experiences that they undergo” (p. 349). Satisfaction does not entirely stem from the pleasures that the tourists derive from the travelling experience, but rather it is the analysis that checks out whether the experience satisfied the consumer as it was expected to (Hunt, 1977, p. 49). Various researches have revealed that satisfaction and the brand’s attitude mean one and the same thing (LaTour & Peat, 1979, p. 433).

Affective reactions have a major influence on the experiences of the consumers’ consumption process with regard to their judgments on post-purchase satisfaction (Madrgal, 1995, p. 212; Spreng, MacKenzie & Olshavsky, 1996, p. 17; Barsky, 1992, p. 54; Oliver, 1993, p. 422). In this case, it is assumed that the satisfaction of the tourists is dependent on the performance of the product, the perceptions of the consumer in relation to the product, and the motivations that the consumers have.

The ratio between the performance and the perception rises as the level of the tourist’s satisfaction also rises (Barsky, 1992, p. 54); the ratio depends on the nature of the experiences that the consumers have in relation to the experience they had envisaged or desired. Dissatisfaction of the consumers come about when there is a major disparity between what the consumers had expected and what they actually experience in terms of the performance of the products.

Various scholars have expressed their criticisms concerning the conceptualization of satisfaction with regard to the expectations that the consumers have. Satisfaction is perceived to have a connection with surprise (Arnould & Price, 1993, p. 26). In addition, Miller (1977) concluded that tourist satisfaction can occur in various forms; for instance, desirable satisfaction, ideal satisfaction, and tolerable satisfaction.

When tourists go for holidays, their satisfaction levels are highly connected to their level of motivation. When the travel destination is attractive, the needs and the motivation of the tourists are highly satisfied (Truong, 2005, p. 229). The perception of the destination encompasses a variety of factors and various attraction sites that the consumer believes to have the capacity to satisfy his/her desires or expectations.

Therefore, when the post-purchase behavior analysis is undertaken, it is expected to make out whether the travel consumers have been satisfied by the tourist products or whether they have been dissatisfied by the same. The analyses of the post-purchase consumer behavior are related to the concept of push and pull satisfaction. When the concept of push and pull satisfaction is likened to motivation, both the tangible and intangible components of the post-purchase analysis can be measured (Truong, 2005, p. 229).

The intention by the tourist to make a purchase depends on their motives relating to both the behavioral and social norms. The motives of the consumers depend on the level of expectations that they have concerning the probability of assuming a certain behavior and the assessment of how they regard it (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1980).

Lam and Hsu (2006) in their study used the theory of reasoned action to show that the intention of the tourists to choose a destination site depends on the recognized behavior and the past behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1980). The image that the travelling tourist portrays depends on the quality of the destination site, the anticipated satisfaction, the eagerness of the tourists to return and their enthusiasm to propose the destination to their friends.

When the destination site is of a high quality, the tourists will be persuaded to return to the site because of the high level of satisfaction he/she experiences; the level of satisfaction will further influence whether the consumers will recommend the destination site to their friends. Further, studies show that the more a tourist visits a site, the more he/she is motivated to return, especially with regard to mature destinations (Kozak, 2001, p. 792).

Decision making process of the elderly tourists

There are three fundamental stages that are involved in the process of decision making by the tourists; the stages include: the pre-decision, the decision and the post-purchase assessment (Crompton & Ankomah, 1993, p. 466; Bentler & Speckart, 1979, p. 457; Um & Crompton, 1990, p. 438; Ryan, 1994).

Before the tourist proceeds to make the purchase, the pre-decision stage normally precedes. This stage normally entails serious decision making by the tourist as he/she has to make the best choice out of the many alternatives. The kind of choices that the tourists have in this stage include: the travel destination, the activities to engage in during the travel and the level of expenditure that the tourist expects to commit. Very many tourists are motivated to travel because of the various activities that they intend to engage in or carry out (Crouch & Jordan, 2004, p. 120; Crompton & Ankomah, 1993, p. 466).

The pre-decision stage gives way for the decision stage. At this point the tourists make decisions paying attention to the time they have available for the travel and the amount of income that they want to commit on the travel. The decision stage is majorly concerned with the purchase of products.

The post-purchase stage stems from the factors that determine the process of making choices and checks whether the tourist has been satisfied with the decisions or the choices that he/she had opted for. This stage, therefore, plays an important role in assessing the likelihood of making the purchase again and also in recommending or opposing the choice or the decision (Abelson & Levi, 1985; Barros & Proença, 2005, p. 300).

Three sets of models have emerged as a result of the interdisciplinary status of the elderly tourists’ behavior. The models include: microeconomic models, structural models and processional models. For the case of microeconomic models, elderly tourists normally have the motive to increase their utilities to the maximum subject to a combination of constraints such as: time, income and the level of technology (Morley, 1992).

For the case of structural models, the connection between the input and output is scrutinized. Consequently, for the case of processional models, the tourist’s judgments are put to examination (Abelson & Levi, 1985).

The classical economic theory is the main basis of the microeconomic model that analyses the behavior of the tourists. When taking into consideration the demand for manageable goods or services, classical economic theory is very instrumental. In addition, the classical economic theory brings into focus the limitations that relate to tourism analysis. Samuelson (1991) asserts that the notion that the tourists strive to maximize the utility that they derive from tourism contributes to the process of tourism analysis.

Moreover, the destination sites for tourists are not considered as objects that can directly be used, but rather products that have characteristics that facilitate the derivation of utility (Lancaster, 1966, p. 140); this utility is subject to various constraints. Morley (1992) brings into focus the utilization of microeconomic theory to the field of tourism. Microeconomic analysis creates a platform that is beneficial for the analysis of the behavior of elderly tourists (Paraskevopoulos, 1977; O’Hagan & Harrison, 1984, p. 922; Song & Witt, 2000).

The whole decision making process of the elderly tourists is analyzed by processional models. The models pay much attention to the underlying factors that influence the decision making process of the travel consumers. In simple terms, processional models give out information that relate to the behavior of the consumers in their decision making process.

There are various factors that influence the decision making process of the tourists; the main outstanding factor is actually the decision process. Tourism products, just like other normal products have several attributes which play the role of distinguishing them from the possible substitute products (Song & Witt, 2000; Lancaster, 1966, p. 140).

Scholarly studies that relate to the analysis of travel motivation are founded on the basis of various models that are considered to be outstanding. These models stem from the perspective of the processional models. The first model is the Nicosia model (1966) which concentrates on the correspondence that occurs between the tourist and the firm, and how the firm convinces the consumer to acquire her products.

Another model dubbed Howard and Sheth’s model (1969) integrated the input notion that describe the behavior of the tourists; in addition, the model states the ways by which the tourists incorporate these inputs in their decision making process. Howard and Sheth’s model has continued to be regarded as the most important model for analyzing the travel motivations of the elderly tourists.

Travel motivation of the elderly tourists can be assessed by paying regard to the analytic analysis of desire, anticipations, conception and satisfaction. Gallarza, Saura and Garcia (2002, p. 63) emphasized on the use of statistical tools (such as multivariate analysis that depend on other analyses like correlation matrix, sampling techniques and regression analyses) on tourism.

Qualitative choice models are very efficient in assessing the behavior of the elderly tourists; such models entirely depend on multinomial logit (Stynes & Peterson, 1984, p. 310; Barros & Proença, 2005, p. 302; Fleischer & Pizam, 2002, p. 118). In the recent past, many academic scholars have applied structural models on researches that relate to the assessment of the travel motivation of the elderly tourists (Baker & Compton, 1998, p. 800).

Research Methodology

Introduction

Methodology is the process of instructing the ways to do the research. It is, therefore, convenient for conducting the research and for analyzing the research questions. The process of methodology insists that much care should be given to the kinds and nature of procedures to be adhered to in accomplishing a given set of procedures or an objective. This section contains the research design, study population and the sampling techniques that will be used to collect data for the study. It also details the data analysis methods, ethical considerations, validity and reliability of data and the limitation of the study.

Research philosophy

For this part, choosing a philosophy of research design is the choice between the positivist and the social constructionist (Easterby, Thorp & Lowe, 2008, p. 67). The positivist view shows that social worlds exist externally, and its properties are supposed to be measured objectively, rather than being inferred subjectively through feelings, intuition, or reflection. The basic beliefs for positivist view are that the observer is independent, and science is free of value. The researchers should always concentrate on facts, look for causality and basic laws, reduce phenomenon to simplest elements, and form hypotheses and test them.

Preferred methods for positivism consist of making concepts operational and taking large samples. The view of the social constructionists is that reality is a one-sided phenomenon and can be constructed socially in order to gain a new significance to the people. The researchers should concentrate on meaning, look for understanding for what really happened and develop ideas with regard to the data.

Preferred methods for the social constructionists include using different approaches to establish different views of phenomenon and small samples evaluated in depth or over time (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2009, p. 87). For the case of analyzing the travel motivations and market segmentation for the elderly, the philosophy of the social constructionists was used for carrying out the research. Because it tends to produce qualitative data, and the data are subjective since the gathering process would also be subjective due to the involvement of the researcher.

Sample selection

Population refers to the total elements that are under investigation from which the researcher draws conclusion (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2009, p. 90). A sample is a subset of the population, i.e. it is a representation of the total population (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2009, p. 90). This study mainly used a non-probability design of sampling. In this design, not every participant in the study has an equal chance of being chosen.

Non-probability sampling design does not utilize much cost and time, hence it is widely preferred. When smaller samples are used, a non-probability research design is susceptible to errors, thus, normally a larger sample size is selected. In addition, it was preferred for the number of observations to be more than the number of variables as a regression analysis was to be conducted.

This study mainly targeted a sample of at least 400 elderly tourists who were aged over 55 years and were travelling to Thailand. Data collection was done by administering questionnaires at the leading tourist destination sites, for instance, Bangkok, Phuket, Chiangmai, and Pattaya. 600 questionnaires were issued out to the respondents, but only 467 questionnaires were collected; 37 questionnaires were spoilt as a result of the respondents’ mistakes, thus, 430 questionnaires were utilized in analyzing the data.

Research design

In line with the main objective of this study which is to analyze the overseas travel motivations and market segmentation for the elderly in the tourism industry, this study employed a cross-sectional research design. Under this design 600 respondents were targeted. They were issued with questionnaires to assist with data collection. The respondents were assured of the confidentiality of their participation.

Statistical method

Descriptive statistics and inferential statistics were both applied in the study in order to test the hypotheses.

Descriptive statics

Descriptive statistics is mostly applicable for analyzing numerical data. It uses distribution frequencies, distribution of variables and measures of central tendencies (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2009, p. 93). The characteristics of the sample chosen will be used to compute frequencies and percentages with regard to the questionnaires.

Inferential statics

Inferential statistics gives the researcher the chance to convert the data into statistical format so that important patterns or trends are captured and analyzed accordingly (Easterby, Thorp & Lowe, 2008, p. 72). Regression analysis is utilized in inferential statistics. Regression analysis is employed to check on the relationship between a dependent variable and independent variable. It allows for the researcher to predict and forecast the expected changes to a dependent variable when one independent variable changes (Easterby, Thorp & Lowe, 2008, p. 72).

Data Collection and Instrumentation

Questionnaires were used to collect the data. The questionnaires were issued to 600 respondents who were mainly elderly tourists. The questionnaire was composed of five parts. Part one purposed to obtain information regarding the personal attributes of the respondents. Part two purposed to obtain information relating to the travel behavior of the tourists and the characteristics of the trip. Part three purposed to obtain information regarding the opinions of the elderly tourists concerning their travel motivations.

A five-point Likert scale (1 – strongly disagree to 5 – strongly agree) was utilized to measure the tourists’ opinions regarding their travel motivation. Part four purposed to capture information relating to 17 characteristics of the travel requirements. The elderly tourists were asked to give a rating concerning the relevance of each characteristic of travel, paying attention to their desired destination.

A five-point Likert scale (1 – strongly disagree to 5 – strongly agree) was utilized to measure the importance variable. Part five purposed to obtain information concerning satisfaction that the elderly tourists derived from the 17 characteristics of travel requirements that were touched on by part four. After collecting the data, the validity of the questionnaires was analyzed by two tourist professionals and two qualified lecturers from a tourism business school.

A pre-test or a pilot test of the questionnaires was conducted and it involved a sample of 150 elderly tourists. The pre-test of the questionnaires was very beneficial in enhancing the validity and the reliability of the questionnaires. The questionnaires’ reliability was evaluated by estimating the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which was found to be 0.9354, suggesting that the questionnaires were very reliable to be used as the preferred instrument for collecting data. There were; however, minor corrections that were done after the pre-test so as to prevent future errors.

Data Analysis Methods

The main objective of the study was to explore on the travel motivations and market segmentation for the elderly. The study utilized structural econometric models to assess the models that comprise the relevant variables that describe the data (Yoon & Uysal, 2005, p. 52). The structural econometric models also allow the researcher to estimate the connections that exist among the variables (Yoon & Uysal, 2005, p. 52). Data from the survey were entered into the Excel spreadsheet program and was analyzed using SPSS and ANOVA analysis.

The statistical tools that were put to use during the analysis of the descriptive data were; measures of central tendency, standard deviation and frequency. On the other hand, the statistical tools that were used to analyze the inferential statistics of the data were: F-test, T-test and level of significance. In addition, Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) was carried out.

IPA is basically a realistic method that is used for elaborating on two perspectives of the tourist attributes, for instance, the level of performance of the tourists, and the perceived importance. IPA was first introduced by Martilla and James (1977), and since then, many researchers have found it useful as an important tool for carrying out research, especially in the field of tourism, hospitality, or business (Farnun & Hall, 2007, p. 70; Jang et al., 2009, p. 65; Koh et al., 2009, p. 722).

Limitation of data collection methods

There have been a lot of concerns on additional budgetary expenses for collection of the data, regardless of whether the gathered data is really genuine or not and whether there may be an explicit conclusion when interpreting and analyzing the data. In addition, some tourists were reluctant to offer some information they deemed confidential and unsafe in the hands of their competitors. This posed a great challenge to the research as the researcher had to take a longer time to find other tourists who were willing to give out adequate information.

Validity and reliability

Validity of the data represents the data integrity and it connotes that the data is accurate and much consistent. Validity has been explained as a descriptive evaluation of the association between actions and interpretations and empirical evidence deduced from the data. More precaution was taken especially when a comparison was made between the tourists’ commitment and attitude. The tourists’ motivation may differ from business to business and may not be identical in an industry.

Reliability of the data is the outcome of a series of actions which commences with the proper explanation of the issues to be resolved. This may push on to a clear recognition of the yardsticks concerned. It contains the target samples to be chosen, the proper sampling strategy and the sampling methods to be employed.

Findings, Data Analysis and Interpretation

Introduction

This section covers the analysis of the data, presentation and interpretation. The results were analyzed using SPPS, ANOVA, regression and correlation analysis.

Descriptive statistics

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

Table 4.1 shows the summary of the demographic characteristics of the respondents who successfully completed the questionnaires.

Table 4.1 Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Table 4.2 Socio-economic and other factors.

The results summarized in the table reveal that out of the 430 respondents who successfully filled out the questionnaires, 65.12% were male and 34.88% were female. Almost half of the respondents (46.05%) were in the age group between 55 and 59 years; 28.14% of the respondents were in the age group between 60 and 64 years; in addition, 25.81% were aged above 65 years. 143 respondents (33.26%) had a bachelor’s degree; 26.28% (n = 113) had a high school level of education.

Moreover, 291 respondents (67.67%) were married, while only 38 respondents (8.84%) were divorced. 173 respondents (40.23%) had an excellent health status; only 8 respondents (1.86%) had a poor health status. The study also found out that 40.23% (n = 173) of the respondents worked on a full-time basis; 14.89% (n = 64) of the respondents worked on a part-time basis; while only 3.72% (n = 16) of the respondents were unemployed. 47.91% of the respondents perceived their economic status as enough.

Consequently, out of the 430 respondents who successfully completed the questionnaires, 27.67% were British tourists, 17.21% had a Dutch origin, 13.72% came from Germany and the rest (41.40%) came from other European countries.

Summary of travel motivation

Table 4.2 shows the summary of travel motivation of the respondents who successfully completed the questionnaires.

Table 4.2 Travel motivation of the respondents (N = 430).

The table above gives the summary of travel motivations of the respondents who had completed their questionnaires successfully. The study found out that the top three travel motivation factors for the elderly tourists were: rest and relaxation; visit to new places; and learning and experiencing new things. This is indicated by the values of their means as 4.13, 3.97, and 3.96 respectively. In addition, the study found out that the bottom three travel motivation factors that least motivated the elderly tourists were: seeking intellectual enrichment (mean = 3.48); exercise physically (mean = 3.10); and visit family and friends (mean = 2.98).

With regard to the analysis of the travel behavior of the elderly tourists, the study found out that 41.40% of the respondents had visited Thailand only once; 31.86% of the respondents had toured Thailand at least four times. In addition, at least half of all the respondents (58.37%) were planning to stay in Thailand for at least 15 days.

The study further found out that 54.42% of the respondents travelled together with their spouses. The main motivating factor that influenced the elderly tourists to visit Thailand was the fact that the tourists regarded the nationals of Thailand as friendly (72.79%). Of all the activities that the tourists desired to engage in, leisure and sight seeing was the leading activity as it was preferred by 72.56% of the respondents.

Moreover, 47.67% of the respondents opted to stay in 4-star hotels; at the same time, 41.86% of the respondents preferred to rent a car to travel around, and their leading source of information was from family and friends (46.74%). 41.86% of the respondents had a daily expenditure of below $100, while 23.25% of the respondents had their daily expenditures ranging between $100 and $120. 33.49% of the respondents confirmed that they liked touring Thailand in January, while 88.60% of the respondents agreed that they will make another visit to Thailand.

Summary of the relevance of tourism attributes of travel requirements

Table 4.3 shows the summary of the relevance of tourism attributes of travel requirements of the respondents who successfully completed the questionnaires.

Table 4.3 The relevance of tourism attributes of travel requirements (N = 430).

430 elderly tourists gave out their ratings with regard to the relevance or importance of the 17 characteristics of travel requirements listed in Table 4.3 above. The results indicate that the most important travel requirement that was considered by the elderly tourists was safety of the destination (mean = 4.19). Location of accommodation and natural attraction followed in that order with means of 4.02 and 4.01 respectively. Consequently, the results further indicate that the least important travel requirements that were considered by the elderly tourists were: hotel accessibility and disability features (mean = 3.41); special events and festivals (mean = 3.40); and leisure activities (mean = 3.15).

Table 4.4 The satisfaction of tourism attributes of travel requirements (N = 430).

430 elderly tourists gave out their ratings with regard to their satisfaction of the 17 characteristics of travel requirements listed in Table 4.4 above. The results indicate that the most satisfying travel requirement that was considered by the elderly tourists was safety of the destination (mean = 4.10). Location of accommodation and natural attraction followed in that order with means of 4.09 and 4.05 respectively. Consequently, the results further indicate that the least important travel requirements that were considered by the elderly tourists were: hotel accessibility and disability features (mean = 3.69); special events and festivals (mean = 3.68); and leisure activities (mean = 3.52).

The F-test and T-test that was carried out during the analysis of the data revealed that the wide disparity that was evident on the age of respondents, their gender, level of education, employment status and health status were considered to be significant factors in deciding the travel requirements.

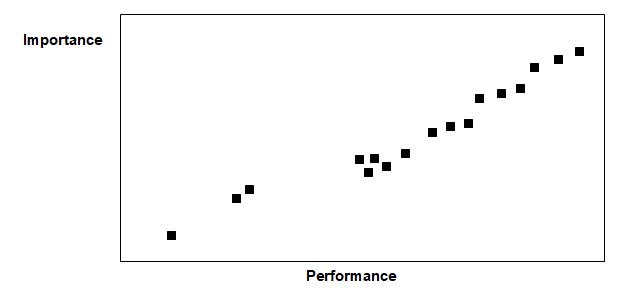

Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA)

IPA was utilized in this study in order to capture both the importance and the level of satisfaction of the 17 attributes that have been explored above. IPA in the context of this study is determined by plotting the ratings of the elderly tourists regarding the importance of the 17 attributes against the level of performance of the attributes.

The importance-performance (IP) space is segmented into four parts, as indicated in Figure 4.1 below. The first quadrant which is at the top left of the IP space shows the factors which are very important but with low levels of satisfaction to the tourists; no factor was found to fall in this category. The second quadrant which is at the top right of the IP space shows the important factors that provide the tourists with a high satisfaction level.

A total of nine factors fell in this category; the factors include: accommodation cost of the trip, types of food or beverages, accessibility, transport, natural, historical and cultural attractions, and security or safety. The third quadrant which is at the bottom left of the IP space shows all the less important factors that provided low satisfaction to the tourists.

A total of eight factors fell in this category; the factors include: hotel’s features of accessibility and disability, comfortable immigration procedures, special festivals, quality of service, leisure activities, medical care and infrastructure. The fourth quadrant which is at the bottom right shows the less important factors that provided high satisfaction levels to the tourists. No factors were found to fall in this category.

NOTE: The squares represent the 17 attributes discussed above.

Table 4.9 ANOVA Analysis results.

Discussion Conclusion and Recommendations

Introduction

This chapter presents the summary of the findings and discussion of the results in accordance to the objectives of this study. Finally, the chapter contains the conclusions and recommendations.

Discussion

Relative studies concerning the travel motivations or behaviors of the elderly tourists have mostly been done in America and Europe. Some of these studies paid much attention to the Taiwanese elderly travelers; just a few studies have dwelt on European elderly tourists who visit Thailand. Even though the Thailand government has taken the initiative to promote the tourism sector, there has been no major increase in the number of European tourists who visit Thailand.

With regard to the results concerning the travel behavior of the elderly tourists, 41.4% of the respondents who successfully filled out the questionnaires confirmed that it was their first time to visit Thailand; 31.86% of the respondents had originated from the western countries and had visited Thailand more than once. This indicates that at least one-third of the respondents were frequent visitors because of the friendly nature of the people in Thailand. The tourists who had visited for the first time got information from their friends or relatives who had previously visited the place and recommended it to them.

From the research findings, it can be pointed out that the main factors that motivated the elderly tourists to travel were: the desire to rest or relax (mean = 4.13), the urge to visit new places (mean = 3.97), and the desire to learn and experience new things (mean = 3.96). These findings are in conformity with the previous studies conducted by Anderson and Langmeyer (1982), Fleischer and Pizam (2002) and Horneman et al. (2002). It is very evident that many elderly travelers in today’s world have more desire to discover new things and ideas than the generation of elderly tourists in the past.

Many respondents cared so much about the safety of their travel destination; this is in agreement with the previous studies done by Hsu (2008), and Lindqvist and Bjork (2000). It is a common practice for many European countries to beef up the security and safety standards of the elderly tourists. With this regard, the tourists who visit Thailand from Europe expect to a similar level of security measures while travelling.

The need for adequate safety and security increase as the tourists grow older. In addition, the study found out that, the other important factor that motivated the elderly tourists was the natural attractions; the elderly tourists are much attracted to feel the sun-and-sea experience and they also enjoy feeling the natural beauty of mountains and forest experience.

Conclusion

Motivation refers to the category of a need or a plight that urges a person to engage in a certain action that is expected to offer him/her. In other instances, motivation has been taken to mean the drive that exists within a person that compels him/her to do a certain thing so as to meet a psychological need or a biological need. Travel motivation is the kind of motivation that is connected to the reason why people decide to travel.

The motivation that is connected to the tourists’ travel encompasses a wide spectrum of the tourists’ behaviors and their previous travel experiences. Examples of motivations that lead people to travel include: the desire to relax, the urge to gain excitement, the need to interact with friends socially, the spirit of adventure, the urge to interact with families, the drive to improve personal status, and the urge to get away from the daily routines or stress.

Every tourist has a great desire to satisfy his/her motivation when they decide to travel. Each tourist has a different interpretation of the concept of satisfaction, thus, its definition is divergent among the various consumers. Many scholars in their research articles have linked the definition of satisfaction to the distinction between expectation and experience.

Bultena and Klessig (1969) gave a definition of satisfactory experience as “a part of the level of the correspondence between the consumers’ desires and the experiences that they undergo” (p. 349). Satisfaction does not entirely stem from the pleasures that the tourists derive from the travelling experience, but rather it is the analysis that checks out whether the experience satisfied the consumer as it was expected to. Various researches have revealed that satisfaction and the brand’s attitude mean one and the same thing.

Travel motivation can be explained as the magnitude of commitment, vigor, and originality in the part of the tourist. For many tour managers, amidst of ever gradually increasing more aggressive business atmosphere of the recent years, finding out, means to motivate the clients. In reality, a variety of varied hypotheses and means of tourist motivation have appeared, extending from increased involvement to monetary incentives and employee empowerment.

For small tourist enterprises, motivation can occasionally be predominantly challenging where the promoters have frequently worked for many years for establishing a company that he may be reluctant to delegate significant authorities to others. But the business owners should be aware of such drawbacks. Some of the issues connected with unmotivated travelers include deteriorating morale, less contentment, and widespread dissuasion. These concerns can reduce incomes, aggressiveness, and efficiency with regard to small scale businesses when they are allowed to exist.

The study found out that the top three travel motivation factors for the elderly tourists were: rest and relaxation; visit to new places; and learning and experiencing new things. This is indicated by the values of their means as 4.13, 3.97, and 3.96 respectively. In addition, the study found out that the bottom three travel motivation factors that least motivated the elderly tourists were: seeking intellectual enrichment (mean = 3.48); exercise physically (mean = 3.10); and visit family and friends (mean = 2.98).

The results further indicate that the most satisfying travel requirement that was considered by the elderly tourists was safety of the destination (mean = 4.10). Location of accommodation and natural attraction followed in that order with means of 4.09 and 4.05 respectively. Consequently, the results further indicate that the least important travel requirements that were considered by the elderly tourists were: hotel accessibility and disability features (mean = 3.69); special events and festivals (mean = 3.68); and leisure activities (mean = 3.52).

Recommendations

The findings of this study are very relevant to the elderly tourists, tourist planners and tourist marketers. It is a good idea for Thailand to implement relevant policies and strategies both in the private sector and in the public sector. One of the relevant policies to be implemented is to carry out a promotional campaign to popularize the country’s tourism sector in order to capture the European market by reaching out the elderly tourists. In addition, Thailand government should beef up the security measures for the visiting elderly tourists.

It is also adequate for the country to improve and protect the physical appearance of tourist destination sites to enable her to be in a competitive position as compared to the other countries. Moreover, the ease of accessibility to the tourist destination sites should be improved so as to give an easy time for the elderly tourists to move around. Accommodation facilities and other social amenities should be upgraded so that they can be up to standard and fit the specifications and the requirements of the elderly tourists.

Statement of contribution

Summary

The main aim of this study was to assess the oversea travel motivations and market segmentation for the elderly. The study explored various factors that motivated the elderly tourists to travel, in line with main objective. The study explored elaborately on the various forms of economic impact analysis with regard to inbound tourism. The study relied on primary data using structured questions to explain the main objective and the data was analyzed using statistical tools like SPSS, and ANOVA analysis.

The study found out that the top three travel motivation factors for the elderly tourists were: rest and relaxation; visit to new places; and learning and experiencing new things. This is indicated by the values of their means as 4.13, 3.97, and 3.96 respectively. In addition, the study found out that the bottom three travel motivation factors that least motivated the elderly tourists were: seeking intellectual enrichment (mean = 3.48); exercise physically (mean = 3.10); and visit family and friends (mean = 2.98).

The results further indicate that the most satisfying travel requirement that was considered by the elderly tourists was safety of the destination (mean = 4.10). Location of accommodation and natural attraction followed in that order with means of 4.09 and 4.05 respectively. Consequently, the results further indicate that the least important travel requirements that were considered by the elderly tourists were: hotel accessibility and disability features (mean = 3.69); special events and festivals (mean = 3.68); and leisure activities (mean = 3.52).

The findings of this study are very relevant to the elderly tourists, tourist planners and tourist marketers. It is also adequate for the country to improve and protect the physical appearance of tourist destination sites to enable her to be in a competitive position as compared to the other countries.

Moreover, the ease of accessibility to the tourist destination sites should be improved so as to give an easy time for the elderly tourists to move around. Accommodation facilities and other social amenities should be upgraded so that they can be up to standard and fit the specifications and the requirements of the elderly tourists.

Contributions and impacts

This study helps to give a clarification on the travel motivations of the elderly tourists. This study is very relevant in today’s world as the number of the elderly tourists is ever increasing and their needs are ever changing. The population of the elderly people in the world has grown rapidly as a result of positive changes in the health sector and improvement of life expectancy age.

11% of the total population in the world was aged at least 60 years at the beginning of the 21st century; it is postulated that the percentage will rise to 20% by the year 2050. In less than 20 years, it is estimated that one third of both Japan’s population and Germany’s population will be at least 60 years of age. In the same way, at least a quarter of France’s population, the UK’s population, and Korea’s population will be at least 60 years of age.

The tourism industry all over the world has developed a keen interest on the growing elderly population as a result of its large size, high purchasing power and more time to commit to travel because they have retired. The elderly people normally have accumulated income or a good pension, thus, they can comfortably pay up the expenses involved in travelling.

The elderly population is highly motivated to take part in leisure activities (for instance, long distance travels) due to the fact that many of them are well educated, have a good income and a good health status. In addition, the elderly tourists have a lot of free time after retirement, thus, making them to be more captivating to the business of tourism that has a varied demand every season. Many scholars have pointed out that the elderly market is very important to tourism industry as they are one of the highest consumers.

This study provides information that is adequate for the country to improve and protect the physical appearance of tourist destination sites to enable her to be in a competitive position as compared to the other countries. Moreover, the ease of accessibility to the tourist destination sites should be improved so as to give an easy time for the elderly tourists to move around. Accommodation facilities and other social amenities should be upgraded so that they can be up to standard and fit the specifications and the requirements of the elderly tourists.

References

Abelson, R. & Levi, A. (1985). Decision Making and Decision Theory. In G.Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 11-32). New York: Random House.

Anderson, B. & Langmeyer, L. (1982). The under-50 and over-50 traveler: A profile of similarities and differences. Journal of Travel Research, 20(4), 20-24.

Arnould, E. & Price, L. (1993). River magic: extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 24-45.

Backman, K., Backman, S. & Silverberg, K. (1999). An investigation into the psychographics of senior nature-based travelers. Tourism Recreation Research, 14(1), 13-22.

Bai, B.X., Jang, S., Cai, L.A. & O’Leary, J.T. (2001). Determinants of travel mode choice of senior travelers to the United States. Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing, 8(3/4), 147-168.

Baker, D. & Crompton, J. (1998). Exploring the Relationship between Quality, Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intentions in the Context of a Festival. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(3), 785-804.

Baloglu, S. & McCleary, K. (1999). A Model of Destination Image Formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(4), 868-897.

Baloglu, S. (1997). The relationship between destination images and socio-demographic and trip characteristics of international travelers. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 3(1), 221-233.

Barcelo, D. (2000). Sample Handling and Trace Analysis of Pollutants: Techniques and Applications. New York: Elsevier.

Barros, C. & Proença, I. (2005). Mixed logit estimation of radical Islamic terrorism in Europe and North America. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49(2), 298-314.

Barsky, J. (1992). Costumer satisfaction in the hotel industry: meaning and meaning and measurement. Hospitality Research Journal, 16(1), 51-73.

Beerli, A. & Martín, J. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31, 657-681.

Bentler, P. & Speckart, G. (1979). Models of attitude behavior relations. Psychological Review, 86(5), 452-464.

Britton, P. B., Samantha J. C. & Terry, W. (1999). Rewards of Work. Ivey Business Journal, 15(2), 20-27.

Bultena, C. & Klessig, L. (1969). Satisfaction in camping: A conceptualization and guide tosocial research. Journal of Leisure Research, 348-364.

Cleaver, M., Muller, T., Ruys, H. & Wei, S. (1999). Tourism product development for the senior market, based on travel-motive research. Tourism Recreation Research, 24(1), 5-11.

Correia, A. & Crouch, G. (2004). A Study of Tourist Decision Processes: Algarve, Portugal. In G. Crouch, R. Perdue, H. Timmermans & M. Uysal (Eds.), Consumer Psychology of Tourism, Hospitality and Leisure (pp. 45-73). Oxon, UK: CABI Publishing.

Correia, A., Valle, P. & Moço, C. (2005). Why People Travel to Exotic Places? Journal of Life, Leisure, and Tourism Research, 13(2), 34-40.

Crompton, J. & Ankomah, P. (1993). Choice set propositions in destination decisions. Annals of Tourism Research, 20, 461-476.

Crompton, J. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacations. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4),408-424.

Crouch, G. & Jordan, L. (2004). The determinants of convention site selection: A logistic choice model from experimental data. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 118-130.

Dann, G. (1981). Tourist motivation – an appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research, 8(2), 187-219.

Dann, G. (1996). Tourists’ images of a destination – an alternative analysis. Recent Advances and Tourism Marketing Research, 1(1), 41-55.

Dann, G.M.S. (2001). Senior Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(1), 238-240.

Easterby, M., Thorp, R. & Lowe, A. (2008). Management Research (3rd ed.). New York: Sage.

Farnun, J. & Hall, T. (2007). Exploring the utility of importance performance analysis using confidence interval and market segmentation strategies. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration, 25(2), 64-83

Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. (1980). Predicting and Understanding Consumer Behavior: Attitude Behavior Correspondence. New York: Prentice Hall.

Fleischer, A. & Pizam, A. (2002). Tourism constraints among Israeli seniors. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 106-123.

Fodness, D. & Murray, B. (1997). Tourist information search. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(3), 503–523.

Fodness, D. (1994). Measuring tourist motivation. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(3), 555-581.

Fridgen, J.D. (1996). Dimensions of Tourism. MI: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Gallarza, M. Saura, I. & Garcia, H. (2002). Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 56-78.

Gartner, W. (1993). Image formation process. In M. Uysal & D. Fesenmaier (Eds.), Communication and Channel Systems in Tourism Marketing (pp. 191-215). New York: Haworth Press.

Gnoth, J. (1997). Tourism motivation and expectation formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 283-304.

Guy, B., Curtis, W. & Crotts, J. (1990). Environmental learning of first-time travellers. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(3), 419-431.

Hall, C. M. (2006). Demography. In D. Buhalis & C. Costa (Eds.), Tourism Management Dynamics: Trends Management and Tools (pp. 9-18). Burlington: Elsevier Butterworth.

Horneman, L., Carter, R., Wei, S. & Ruys, A. (2002). Profiling the senior traveler: an Australian perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 41(1), 23-38.

Howard, J. & Sheth, J. (1969). The Theory of Buyer Behavior. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Hsu, C.H.C. & Huang, S. (2008). Travel motivation: a critical review of the concept’s development. In A.G. Woodside & D. Martin (Eds.), Tourism Management: Analysis, Behavior and Strategy (pp. 50-65). Cambridge: CAB International.

Hsu, C.H.C. (2001). Importance and dimensionality of senior motor coach traveler choice attributes. Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing, 8(3/4), 51-70.

Huang, L. & Tsai, H.T. (2003). The study of senior traveler behavior in Taiwan. Tourism Management, 24(1), 561-574.

Hunt, H. (1977). CS/D – overview and future directions. In H. Hunt (Ed.), Conceptualization and measurement of consumer satisfaction and dissatisfaction (pp. 47-61). Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute.

Jamrozy, U., Backman, S. & Backman, K. (1996). Involvement and opinion leadership in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(4), 908-924.

Jang, S., Ha, S. & Silkes, C.A. (2009). Perceived attributes of Asian foods: from the perspective of the American customer. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(1), 63-70.

Jang, S.C. & Wu, C.M.E. (2006). Senior travel motivation and the influential factors: an examination of Taiwanese seniors. Tourism Management, 27(1), 306-316.

Javalgi, R.G., Thomas, E.G. & Rao, S.R. (1992). Consumer behavior in the US, pleasure travel marketplace: an analysis of senior and non-senior travelers. Journal of Travel Research, 31(2), 14-20.

Kinni, T. B. (1994). The Empowered Workforce. Industry Week, 10(2), 9-14.

Koh, S., Jung-Eun, J. & Boger, C.A. (2009). Importance-performance analysis with benefit segmentation of spa goers. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(5), 718-735.

Koss, L. (1994). Hotel developing special packages to attract senior travelers. Hotel and Motel Management, 209(3), 30-37.

Kozak, M. (2001). Repeaters’ behaviour at two distinct destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3), 784-807.

Lam, T. & Hsu, C. (2006). Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination.Tourism Management, 27(4), 589-599.

Lancaster, K. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74(2), 132-157.

LaTour, S. & Peat, N. (1979). Conceptual and methodological issues in consumer satisfaction research. Advances in Consumer Research, 6(1), 431-437.

Lindqvist, L.J. & Bjork, P. (2000). Perceived safety as an important quality among senior tourists. Tourism Economics, 6(2), 151-158.

Littrell, M.A. (2004). Senior travelers: tourism activities and shopping behaviors. Journal of Vacation and Marketing, 10(4), 348-362.

Madrigal, R. (1995). Cognitive and effective determinants of fan satisfaction with sporing event attendance. Journal of Leisure Research, 27(3), 205-227.

Martilla, J.A. & James, J.C. (1977). Importance-performance analysis. Journal of Marketing, 41(1), 77-79.

McCabe, A. (2000). Tourism motivation process. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(4), 1049-1052.

Miller, J. (1977). Studying satisfaction, modifying models, eliciting expectations, posing problems, and making meaningful measurements. In J. Hunt (Ed.), Conceptualization arul measurement of consumer satisfaction and dissatisfaction (pp. 36-51). Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute.

Mohsin, A. & Ryan, C. (2003). Backpackers in the northern territory of Australia. The International Journal of Tourism Research, 5(2), 113-121.

Money, R. & Crotts, J. (2003). The effect of uncertainty avoidance on information search, planning and purchases of international travel vacations. Tourism Management, 24(1), 191–202.

Morley, C. (1992). A microeconomic theory of international tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(1), 250-267.

Moutinho, L. (2000). Strategic Management in Tourism. New York: CABI Publishing.

Nicosia, F. (1966). Consumer Decision Process. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

OHagan, J. & Harrison, M. (1984). Market shares of U. S. tourist expenditures in Europe: An econometric analysis. Applied Economics, 16(6), 919-931.

Oliver, R. (1993). Cognitive, affective, and attributes base of the satisfaction response. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 418-430.

Paraskevopoulos, G. (1977). An econometric analysis of international tourism. Athens: Centre of Planning & Economic Research.

Pearce, P. (1982). Perceived changes in holiday destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(2), 145-164.

Pearce, P. (1982). The Social Psychology of Tourist Behavior. Oxford: Pergamon.

Robson, C. (2002). Real World Research (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

Romsa, G. & Blenman, N. (1989). Vacation patterns for the elderly German. Annals of Tourism Research, 16(1), 178-188.

Ryan, C. (1994). Leisure and tourism – The application of leisure concepts to tourist behaviour- a proposed model. In A. Seaton (Ed.), Tourism the State of the Art (pp. 36-57). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Samuelson, P. (1981). Economia (11th ed.). Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, R. (2009). Research Methods for Business Students (5th ed.). New York: Prentice Hall.

Sellick, M.C. & Muller, T.E. (2004). Tourism for the young-old. In T.V. Singh (Ed.), New Horizons in Tourism: Strange Experiences and Stranger Practices (pp. 163-180). Cambridge: CABI Publishing.

Sheth, J., Newman, B. & Gross, B. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: a theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 22, 159-170.

Shoemaker, S. (1989). Segmentation of the senior pleasure travel market. Journal of travel research, 27(3), 14-22.

Shoemaker, S. (2000). Segmentation of the market: 10 years later. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 11-26.

Song, H. & Witt, S. (2000). Tourism Demand Modelling and Forecasting: Modern Econometric Approaches. Oxford: Pergamon.

Spreng, R., Mackenzie, S. & Olshavsky, B. (1996). A re-examination of the determinants of consumer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 60(3), 15-22.

Stynes, D. & Peterson, G. (1984). A review of logit models with implications for modelling recreational choices. Journal of Leisure Research, 16(1), 295-310.

Truong, T. (2005). Assessing holiday satisfaction of Australian travellers in Vietnam: An application of the HOLSAT model. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 10(3), 227-246.

Um, S. & Crompton, J. (1990). Attitude determinants in tourism destination choice. Annals of Tourism Research, 17, 432-448.

Uysal, M., Mclellan, R. & Syrakaya, E. (1996). Modelling vacation destination decisions: a behavioural approach. Recent Advances in Tourism Marketing Research, 57-75.