Background and Analysis of the Problem

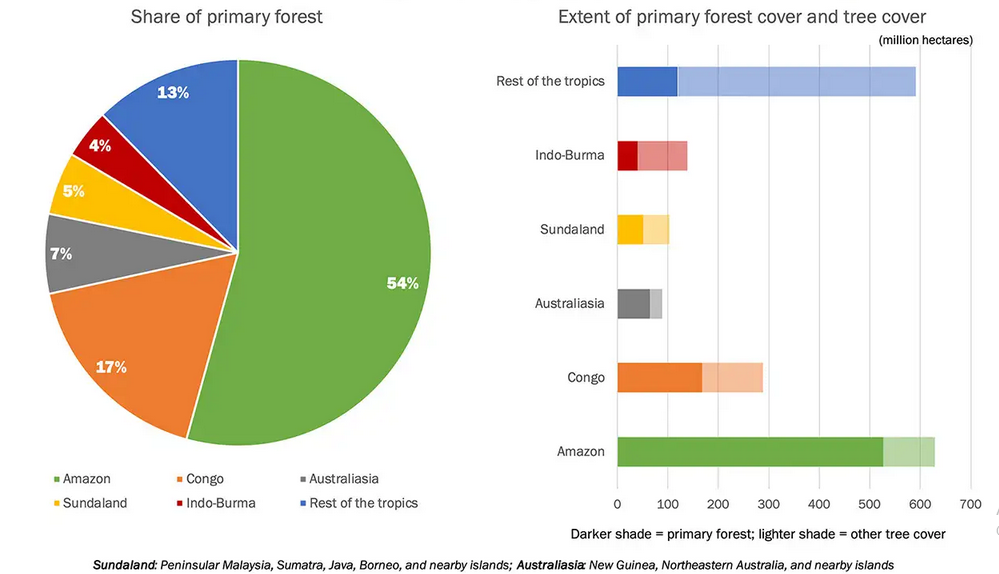

The Amazon Rainforest is found in South America and covers a large landmass spanning several countries, including Brazil, Bolivia, Peru (Nepstad et al., 2009). Compared to the overall size of the South American continent, the geographical cover of the natural ecosystem is equivalent to 40% of its landmass (Butler, 2020). The Amazon Rainforest is one of the world’s most important ecosystems because of its role in regulating oxygen and carbon cycles in the atmosphere (Bruner et al., 2020). It is also home to one of the world’s most complex and sophisticated natural ecosystems that includes rivers, streams, seasonal forests, and natural habitats for various species of plants and animals. According to figure 1 below, Amazon emerges as one of the world’s largest rainforests based on its forest and tree coverage.

As highlighted in figure 1 above, Amazon rainforest is among the world’s most important ecosystems because of its vast geographical coverage, which stretches more than 600 million hectares (Butler, 2020). Other important ecosystems are found in the Congo, Australasia, Sunderland, Indo-Burma, and the rest of the Tropics (Butler, 2020). Due to its vastness, the Amazon rainforest is made up of various ecosystems and types of vegetation, including savannahs, seasonal rainforests, and flooded forests (Butler, 2020). In this regard, the Amazon rainforest is rich in natural ecosystems, some of which are only exclusively found on the wooded area.

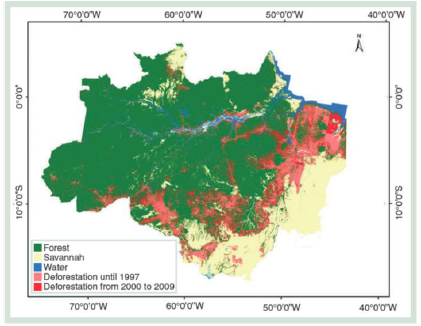

The richness and importance of the Amazon Rainforest depends on the protection and conservation of the above-mentioned natural ecosystems. However, recently, there has been a rapid increase of deforestation in the protected area, thereby threatening its sustainability (Araujo et al., 2019; WWF, 2020). Reports indicate that Amazon’s landmass is depreciating at an alarming rate, with recent statistics suggesting that the forest loses a tree cover that is equivalent to the land size of 30 football fields every minute (World Bank, 2020). Additional statistics from the World Bank (2020) give extra details of the destruction by indicating that up to 600,000 square kilometers of tree cover has been lost due to deforestation. Figure 2 below shows the pattern of destruction in the forest, with the red colored zones, signifying the most affected regions of the wooded area, while the green covered sections showing areas that there is still abundant forest cover.

The rapid rate of deforestation represented by the red colored zones in figure 2 above can be traced to the 1980s period when Brazil and neighboring countries were experiencing a rapid rate of industrial growth, which created an increase in resource demand that thereafter led to a surge in deforestation (Ometto et al., 2011). It is estimated that about 80% of the lost forestland in the red zone above started at this time (World Bank, 2020). If this rate of deforestation is allowed to continue, the integrity of the Amazon Rainforest may be negatively affected, including communities that depend on the forest for their sustenance.

The importance of protecting the forest naturally makes one curious to know of the causes of deforestation and reasons for the ineffectiveness of existing policies in containing the ongoing destruction of the forest. Stemming from this curiosity, scholars highlight several reasons for the current situation. They say the main driver is unplanned farming, which has seen large swathes of forested land cleared to pave way for agricultural activities (Ometto et al., 2011). Large-scale agriculture was also mostly responsible for the degradation of the forest with most accounts of deforestation programs completed in the 2000s, suggesting that cattle ranching were responsible for three-quarters of the reasons govern to cut down trees in the forest. Agriculture-driven deforestation activities have been witnessed throughout much of the history that communities living in the Amazon have practiced subsistence farming by cutting down trees to create arable agricultural land. This reason has been highlighted as a primary catalyst of deforestation in the rainforest (World Bank, 2020). However, in the latter part of the 20th century, researchers have opined that the main driver of deforestation in the Amazon has changed from agriculture-driven destruction to commercially-driven logging activities happening in countries and communities that border the rainforest (Butler, 2020; Ometto et al. 2011). Stated differently, people are now venturing into the forest to get natural resources that they would use as raw materials for various economic activities.

The exploitation of the Amazon Rainforest for commercial reasons has been aided by several factors. Notably, the development of roads in the forest has facilitated the depletion of forest cover in the woodland by giving farmers an opportunity to access protected areas and cut tress or participate in logging activities, while using the same network to transport their loot to factories and towns (Butler, 2020; Ometto et al. 2011). Opportunistic land speculators have also used the developing road networks to clear large tracts of land and sell them for a profit. Collectively, these factors have contributed to the deforestation of the Amazon and some of them are yet to be fully addressed.

Despite the worrying rate of destruction in the Amazon, the rainforest is still home to many indigenous communities, who are among a wider group of stakeholders engaged in activities aimed at protecting or exploiting the forest. Relative to this assertion, Rausch and Gibbs (2021) say that about 30 million people live in the Amazon rainforest and agriculture is their main economic activity. Other local community members engage in traditional medicine, while some of them are involved in the textile industry (Butler, 2020; Ometto et al. 2011). Most of these communities use rivers within the Amazon rainforest as a mode of transport for their goods, while wood, cut form trees, supports a vast number of logging industries in cities and towns located within the forest.

Other stakeholders in the Amazon rainforest are big and small businesses that operate in the area and the government. The task of protecting Amazon’s forestland has been reserved for government authorities who understand the unique needs of each zone of the forest’s landmass (Pfaff et al., 2015; Moutinho et al., 2016). However, they have failed to achieve their intended goal, which is to reduce or minimize the rate of ecological destruction in the forest. This outcome is partly caused by the failure to account for all factors influencing ecological sustainability when developing policy proposals. In other words, at the core of their design is an “extraction mentality” that is premised on resource exploitation, as opposed to environmental conservation (Evangelista-Vale et al., 2021). In this regard, current policies support efforts to build more roads and expand large-scale livestock rearing at the expense of existing ecological considerations.

The Amazon Rainforest is important to Brazil’s socioeconomic sustenance because most of its ecological systems are dependent on the forest (Viana, 2008). For example, most of the rainwater supporting agricultural activities in the country and, by extension, its economy, comes from atmospheric vapors that originate from the Amazon (Viana, 2008). Additionally, the rainwater used to support life in most of Brazil’s major cities comes from the same source. Particularly, the health of the country’s water pipeline systems, agricultural industry, and power plants that generate energy using hydroelectric means, are dependent on water sources from the Amazon (Viana, 2008). Therefore, conservation efforts in the rainforest are important to the sustenance of Brazil’s infrastructure and economy.

It is also essential to analyze Brazil’s policy regime of environmental protection to mitigate the effects of deforestation. This analysis may have policy implications on Brazil’s agricultural policies and land-use regime, with spillover effects being noted in logging and timber industries that benefit directly or indirectly from deforestation in the Amazon (Assuncao et al., 2015; Stabile, 2020; Yanai et al., 2020). This policy analysis report is domiciled in the evaluative, as opposed to the selection stage of policy analysis because relevant policy programs relating to Amazon’s conservation efforts have been identified below, and there is a need to understand their merits and shortcomings to be able to come up with more suitable options.

Critique of Policy

The scale of environmental destruction witnessed in the Amazon rainforest has necessitated the Brazilian government’s quest to develop robust and effective policies to address the problem. However, marred by conflicts of interest, lack of foresight and technical knowhow, most policy proposals introduced in the country have either failed to achieve their intended goals or been unable to sufficiently do so. For example, in 2006, the Brazilian government reformed its forest policy laws to make them more effective in curbing deforestation in the Amazon (Bauch et al., 2009). This policy change consolidated conservation efforts in the hands of one organization Brazilian Institute of Environment and renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA). Its mission was to stop logging activities within the forest and apprehend those who are supporting the vice. However, it was unable to accomplish this goal because of the failure to understand multi-stakeholder dynamics that explain deforestation in the Amazon.

Originally, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and renewable Natural Resources was given the task of protecting the country’s natural protected areas and reserves. The agency also played the role of facilitating forest development in areas where they have a direct mandate of doing so and adopted collaborative development strategies in regions that local community members had dominant interests (Bauch et al., 2009). IBAMA used forest concessions, developed by both community leaders and government agencies, to develop proposals that would protect the livelihoods of community members at protect the environment at the same time (Bauch et al., 2009). These initiatives were designed to promote integrated development as a common framework for tackling environmental issues in the Amazon. However, various issues, including lengthy bureaucracies, decentralization jitters, and delays brought by litigation from agencies representing commercial interests in the Amazon, undermined them (Araujo et al., 2019; WWF, 2020). Consequently, there is little progress to show in advancing the conservation cause at Amazon.

Based on the insights highlighted above, the Brazilian government has been on the forefront in developing a policy framework that would merge the interests of different players whose contribution is needed in developing a sustainable solution for Amazon’s deforestation crisis (Sills et al., 2020). Most of the initiatives developed to complement this goal are guided by the right objectives but are weak in implementation and in assessing pertinent issues affecting local communities. For example, some of the government’s policy responses to minimize deforestation in the Amazon have been too critical and overarching in their mandate of regulating economic activities in the Amazon. Blacklisting local municipalities for having high deforestation rates is one such example (Sills et al., 2020). Some of these municipalities have complained that the ranking system is unfair because it fails to take into account prevailing social, economic, and political differences affecting communities and industries that are cutting down trees in the Amazon (Sills et al., 2020). Therefore, a moderate response to highlighting policy weaknesses affecting Amazon’s conservation efforts is sought.

Political developments in Brazil and the ineffectiveness of existing policy proposals to mitigate the effects of deforestation have also contributed to the failure of government-led policy interventions. For example, misinformed political declarations made by former President Michel Temer undermined conservation efforts in the Amazon rainforest because they dissuaded locals from protecting the forest (Pereira, 2019). In addition, the effects of failed political promises to increase financial allocations to the Ministry of Environment, which is tasked with the responsibility of protecting and managing the forest, have compounded the problem. Consequently, government authorities have been unable to police logging activities in the forest due to poor resourcing and the lack of political will from the country’s top leadership (Pereira, 2019). This weakness in implementation plans means that Brazil’s political class has played a critical role in undermining conservation efforts at the Amazon rainforest.

Although the current policy regime is intended to reduce deforestation levels in Brazil, the insights highlighted above suggest that current policy and regulatory frameworks undermine this goal because by creating conditions that rewards environmental destruction for the sake of social empowerment (Rausch and Gibbs, 2021). Remarkably, a distorted understanding of sustainable development goals, whose achievement is hindered by the quest to meet short-term economic interests, such as employment, at the expense of long-term goals, negatively influences the effects of the current policy environment on conservation efforts at the Amazon. Andrade (2020) has delved deeper into this issue by stating that most concepts of environmental sustainability are designed with cultural and economic implications in mind. However, the current policy regime on environmental management policies in Brazil fails to acknowledge cultural variations and economic differences of various communities surrounding the Amazon.

These gaps in implementation create variations in policy implementation performances across various government agencies that operate in the Amazon. The disintegration of the vision to protect the forest has also made it difficult to develop a holistic conservation plan. Consequently, it is crucial to come up with new policy proposals to address this need by evaluating alternative policy options that could be pursued to improve conservation efforts at the Amazon.

Policy Alternatives

Four policy alternatives outlined below are aimed at addressing some of the policy weaknesses of the current plan to conserve the Amazon rainforest. They include maintaining the status quo, reclassifying sections of the forest as protected areas, replenishing deforested areas, and adopting a place-based approach to conservation.

Policy Alternative 1: Maintaining the Status Quo

The first policy alternative that can be pursued in Amazon’s deforestation crisis is non-intervention. If this policy alternative is adopted, deforestation will continue unabated and governments, or other stakeholders involved, will not take any remedial action to address the problem. This strategy has far-reaching implications not only to countries that host the Amazon rainforest, such as Brazil and Peru, but also to the international community (Assuncao et al., 2015; Stabile, 2020; Yanai et al., 2020). Again, from an international perspective, a non-intervention strategy would catalyze the effects of global warming because deforestation is linked to the loss of forest cover and drought (Amazon Aid Foundation, 2020). This could happen through diminished rainfall and lower levels of moisture in the atmosphere because of lost tree cover. The same situation could lead to wildfires, which would naturally destroy vegetation cover and the natural habitat for communities and animals that live in the forest.

A non-intervention strategy has implications on migratory animals and the long-term makeup of the biodiversity in the Amazon rainforest as well. For example, lost tree cover could disrupt natural migratory corridors for rare animals living in the forest, such as the Amazon River Dolphin and Jaguars (Amazon Aid Foundation, 2020). Inaction would mean that animals become more vulnerable to attacks because of lost forest cover, especially if they depend on contiguous forests to migrate from one patch of the forest to another in search of food. Alternatively, the loss in biodiversity due to deforestation could happen through the loss of habitat and food for animals living in the forest. Supporting this assertion are statistics, which show that about 100,000 species of animals are lost annually due to deforestation (Amazon Aid Foundation, 2020). Overall, a non-intervention strategy would not only affect local communities living in the forest but also animals and wildlife habitat that characterize the zone. Species of animals that depend on those facing extinction will also suffer from biodiversity loss, thereby compounding the impact of a non-intervention strategy. Therefore, doing nothing has far-reaching implications on communities, wildlife and the natural habitat of the forest.

Policy Alternative 2: Reclassifying Sections of the Forest as Protected Areas

Given the weaknesses of the current policy regime in regulating economic activities at the Amazon rainforest, there is a need to undertake extensive reforms that will reclassify sections of the forest as protected areas after they were lost to farmers. This policy proposal is aimed at reversing some of the losses accrued due to the invasion of large-scale farming activities in the forest (Assuncao et al., 2015; Stabile, 2020; Yanai et al., 2020). Most entrepreneurs who run the large-scale farmlands in the forest were individuals who had the power to lobby for policy changes that reclassified old forested lands into agricultural farmland, complete with private ownership documents (Amazon Aid Foundation, 2020). Reclassifying sections of the forest land as protected areas would reverse this loss.

To complement this goal, authorities should create a policy framework for retiring some of these large-scale farmers who will be relinquishing their property back to the state. In the long-term, agricultural activities undertake in the forest should be approved within a sustainable infrastructure matrix, as proposed by the WWF (2020). This proposal is centered on recognizing the ecological effects of economic activities by factoring in their value in the country’s taxation regime, especially on activities that depend on logging, producing crops, and cattle rearing. Thus, after repossessing private property, a framework for future engagements of commercial partners will be developed to provide a model for developing sustainable infrastructure.

Policy Alternative 3: Replenishing Deforested Areas

Replenishing deforested areas is an alternative strategy that could be adopted to improve the sustainability of the Amazon rainforest. This strategy could be multipronged to include the involvement of different stakeholder groups. For example, the support of community members could be sought to maintain the replenished areas. Relative to this assertion, Browder (2002), and Weber et al. (2011) proposed the integrated conservation and development project (ICDP) model to achieve this goal. It advocates for the involvement of community groups in policy implementation processes.

Critics have questioned the viability of adopting the ICDP model because of the financial costs associated with its implementation. Particularly, they have drawn attention to the lack of a consolidated fund for implementing such initiatives, especially considering there are different stakeholder groups with varied stakes involved (Browder, 2002; Weber et al., 2011). To understand the extent and implications of this problem on conservation efforts at the Amazon, it is important to contextualize the issue to a country-specific framework of analysis. In Brazil, this problem stems from the political establishment in the country, through the Office of the President and the Ministry of Environment, which has failed to allocate adequate funds towards conservation efforts at the forest (WWF, 2020). To address this problem, the financing framework supporting financing activities at the national governing council of the forest’s management body needs to be restructured.

This proposal may involve donor participation at both private and public levels through the establishment of a common fund. The resources could be used to expand policy implementation activities at the forest and purchase vital resources for patrolling vast swaths of land by government authorities. Realizing the full benefits of this plan may involve changing the financial policy regime of the government to include contributions from both private and private players to create a common pool of funds for financing policing activities.

Policy Alternative 4: Adopting a Place-Based Approach

Changing Brazil’s policy regime of conserving the Amazon from one that is heavily government-centered to a place-based approach would boost efforts to preserve the forest. Notably, this plan will help to curb the illegal expansion of agricultural land in the forest (Scholz,

2005). Furthermore, it is designed to ensure that all players or stakeholders involved in conservation efforts complete their duties (WWF, 2020). This goal will be achieved by blending two approaches to environmental conservation. The first one is premised on developing programs that involve the contribution of government agencies in management (Assuncao et al., 2015; Stabile, 2020; Yanai et al., 2020). Comparatively, the second one should be focused on forging partnerships between market-based players in logging, mining, livestock raisers, and agricultural producers (WWF, 2020). Such engagements may be localized using the place-based conservation approach where efforts to protect the forest will be spearheaded by local authorities, subject to the terms of the partnership agreements described above.

A place-based approach shifts the policy focus from a protection-based plan to one that caters for ongoing and current interests of community members that live in the forest. It stems from a growing body of literature questioning the sustainability of plans aimed at ejecting communities, which depend on forests for their sustenance, to create a “wilderness” (Assuncao et al., 2015; Stabile, 2020; Yanai et al., 2020). Evidence suggests that some of these local community members are willing to fight to protect their lives and livelihoods if they face such threats and would oppose attempts at relocating them from forests at any cost (Assuncao et al., 2015; Stabile, 2020; Yanai et al., 2020). A place-based approach emerges as an alternative way of addressing this issue by striking a balance between the achievement of biodiversity goals and human settlement concerns (Bray & Velázquez, 2009). Brondizio et al. (2021) contributes to this discussion by adding that a place-based approach can be implemented as individual or community-based programs. They suggest that such initiatives are responsible for promoting regional stability in various places where there have been tensions between community groups and conservationists (Brondizio et al., 2021). The existing body of evidence also suggests that this place-based approach is linked with value aggregation, improved market access, value enhancements and changes in production systems (Brondizio et al., 2021; Assuncao et al., 2015; Stabile, 2020; Yanai et al., 2020). Broadly, this initiative has the highest potential of promoting sustainable development initiatives at the Amazon.

The idea behind adopting a place-based approach to conservation is to encourage stakeholders to adopt practices that support the Amazon forest as opposed to destroying it. Community members should be of critical importance in implementing this policy proposal because they live in the forest and could play a pivotal role in conserving it from within (Scholz, 2005). A program could be introduced to sign up community members and reward them for taking efforts that lead to the conservation of the forest. This plan may involve constructing small-scale rudimentary business centers to enable communities appreciate the importance of the forest to their daily lives. This proposal also has the potential of providing local communities that live in the forest with an opportunity to develop a holistic package or understanding of business capacity building (Yanai et al., 2020). This program may also involve providing financial support to community members who choose to stop engaging in illegal logging activities or other ventures that accelerate the depletion of the forest. Instead of leaving them without an alternative source of income, the program would provide them with financial support to minimize the impact of career change on their lives.

PESTLE Feasibility Analysis

For purposes of understanding the feasibility of implementing the above-mentioned policy alternatives, it is important to understand the effects of environmental factors on the policy adoption process. This process underscores the importance of reviewing the political, economic, social, technological, legal, and environmental aspects of the policy implementation plan. The PESTLE analysis highlighted in table 1 below will be used to carry out this review.

Based on the five elements of the PESTLE analysis identified above, each of the policy alternatives highlighted in this document is ranked and the scores presented in table 2 below based on three ranks. The first rank signifies a low rate of adaptation, rank 2 denotes a medium level of adoption, while the third rank signifies a high rate of adoption. Table 2 below highlights the PESTLE Matrix analysis for each of the policy alternatives selected.

Table 2. PESTLE Matrix Evaluative Criteria (Source: Developed by Author)

The feasibility of implementing the above-mentioned policy initiatives is dependent on three key factors: availability of financing, local community adoption, and government buy-in. These three criteria are selected for the current analysis because they represent the interest of the three stakeholder groups in Amazon forest conservation – businesses, local communities, and the government.

Recommendations

Overall, it is crucial to take action to mitigate the adverse effects of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. Implementing Place-Based Conservation Programs scored the highest overall, making it the best policy alternative for comprehensively tackling the Amazon deforestation problem. In addition, it is the alternative most likely to bring all the stakeholders together. Changing the policy approach of the Brazilian government to reduce the effects of deforestation will play a key role in promoting the development of a “green” economy, with localized plans catering to the needs of all involved, promoted by the synergetic cooperation between local, state, and federal government agencies, non-profit organizations, local citizens, and business enterprises. This proposal will act as a deterrent to the ongoing deforestation practices at Amazon. The recommended policy will help The Brazilian Ministry of Environment to take action to protect all of Brazil’s natural resources, most importantly, those from the Amazon Forest. However, the plan should involve all stakeholders to improve their buy-in.

References

Amazon Aid Foundation. (2020). Effects of deforestation on the Amazon.

Andrade, F. M. (2020). Sustainable development in the Brazilian Amazon: Meanings and concepts. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 28(187), 1-12.

Araujo, C., Combes, J., & Feres, J. (2019). Determinants of Amazon deforestation: The role of off-farm income. Environment and Development Economics, 24(2), 138-156.

Assuncao, J., Gandour, C., & Rocha, R. (2015). Deforestation slowdown in the Brazilian Amazon: Prices or policies? Environment and Development Economics, 20(2), 697-722.

Bauch, S., Sills, E., Rodriguez, L., McGinley, K., & Cubbage, F. (2009). Forest policy reform in Brazil. Journal of Forestry, 2(2), 132-138.

Bray, D. B., & Velázquez, A. (2009). From displacement-based conservation to place-based conservation. Conservation & Society, 7(1) (2009), 11-14.

Brondizio, E., Anderson, K., de Castro, F., Futemma, C., Londres, M., Siani, S., & Salk, C. (2021). Making place-based sustainability initiatives visible in the Brazilian Amazon. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 4(9), 66-78.

Browder, J. O. (2002). Conservation and development projects in the Brazilian Amazon: Lessons from the community initiative program in Rondonia. Environmental Management, 29(6), 750-762.

Bruner, A., Ayllon, J., & Jerico-Daminello, C. (2020). Comparative analysis of conservation agreement programs in the Amazon.

Evangelista-Vale, J. C., Weihs, M., José-Silva, L., Arruda, R., Sander, N.L., Gomides, S.C., Machado, T.M., Pires-Oliveira, J.C., Barros-Rosa, L., Castuera-Oliveira, L., Matias, R. A., Martins-Oliveira, A.T., Bernardo, C. S., Silva-Pereira, I., Carnicer, C., Carpanedo, R. S., & Eisenlohr, P. V. (2021). Climate change may affect the future of extractivism in the Brazilian Amazon. Biological Conservation, 257(2), 1-10.

Moutinho, P., Guerra, R., & Azevedo-Ramos, C. (2016). Achieving zero deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: What is missing. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 4(1), 1-10.

Nepstad, D., Soares-Filho, B., Merry, F., Lima, A., Moutinho, P., & Carter, J. (2009). The end of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Science, 326(5958), 1350-1351.

Ometto, J. P., Aguiar, A. P., & Martinelli, L. A. (2011). Amazon deforestation in Brazil: Effects, drivers and challenges. Carbon Management, 2(5), 575-585.

Pereira, E. (2019). Policy in Brazil (2016-2019) threatens conservation of the Amazon rainforest. Environmental Science and Policy, 100(3), 8-12.

Pfaff, A., Robalino, J., Herrera, D., & Sandoval, C. (2015). Protected areas impact on Brazilian Amazon deforestation: Examining conservation development interaction to inform planning. PLoS ONE, 10(7), 1-17.

Rausch, L. L., & Gibbs, H. K. (2021). The low opportunity costs of the Amazon Soy Moratorium. Frontier for Global Change, 4(2), 1-19.

Scholz, I. (2005). Environmental policy cooperation among organized civil society, national public actors, and international actors in the Brazilian Amazon. The European Journal of Development Research, 17(4), 681-705.

Sills, E., Pfaff, A., Andrade, L., Kirkpatrick, J., & Dickson, R. (2020). Investing in local capacity to respond to a federal environmental mandate: Forests and economic impacts. World Development, 1(29), 1-13.

Stabile, M. (2020). Solving Brazil’s land use puzzle: Increasing production and slowing Amazon’s deforestation. Land use Policy, 91(3), 1-11.

Viana, V. M. (2008). Forest conservation allowance: An innovative mechanism to promote health in traditional communities in the Amazon. Estudos Avançados, 22(64), 143-153.

Weber, J., Sills, E. O., Bauch, S., & Pattanayak, S. K. (2011). Do ICDPs Work? An empirical evaluation of forest-based microenterprises in the Brazilian Amazon. Land Economics, 87(4), 645-681.

World Bank. (2020). Government policies and deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon region (English).

WWF. (2020). Deforestation fronts. Web.

Yanai, A. M. Graça P. A., Escada, M. S., Ziccardi, L. G., & Fearnside, P. M. (2020). Deforestation dynamics in Brazil’s Amazonian settlements: Effects of land tenure concentration. Journal of Environmental Management, 268(23), 1-11. Web.