Among contemporary Czech artists, Jiří Kovanda stands out with his quiet, almost fragile contribution. According to Menegoi (2007), Kovanda is “a famous artist that you don’t know” (para. 1). His perception and attitude in terms of art history can be discussed in regard to the relevant events on the national and global scene. Kovanda began his artistic career in the context of Czechoslovak normalization and carried out small, subtle incursions into Prague, the city where he lived.

He focused on a cast glance, a touch, a hesitant shifting from one foot to another, and similar discreet actions. Kovanda’s audience was mostly unaware that it observed performance since his actions were invisible in a familiar environment. This paper aims to discuss how the question of Kovanda’s perception and attitude to the world, important for understanding his work, was dealt with in retrospect.

Conceptualism and Its Characteristics

First, it is crucial to consider the theory of conceptualism to better understand Kovanda’s work in the history of art. Conceptualism is a postmodern trend that combines the creative process and the means of its study (Smith, 2017). In other words, works of conceptual art take the most unexpected form, such as photographs, texts, photocopies, telegrams, figures, graphs, diagrams, reproductions, and objects that have no functional purpose.

They all are realized as a pure artistic gesture, free from any plastic shape. The environment in which the works of conceptualism are demonstrated or a part of which they are can be a street, road, field, forest, coast, mountains, and others. Many conceptual works use natural materials in their pure form, such as earth, bread, snow, grass, ashes. Painting, performance, and installation are known as the main areas of conceptualism realization. Absurdity, silence, inaction, space, and forms free from sense are the means by which conceptualists try to draw attention to the possibility of the existence of spaces free from ideology in culture. Conceptual creativity confirms the life and existence of a human.

Works of conceptualism are often simple gestures or projects that indicate only the possibility of the emergence of art. Pointless play is an important component of conceptual art since it activates life (Smith, 2017). It confirms the human existence since art as an idea arises and occurs only as a product of human life. Followers of conceptualism are convinced that their paintings, sculptures, installations and performances should evoke not emotions in the viewer, but a desire to intellectually rethink what they saw. Conceptualism is not commercial art, since its objects for creativity can be any household items, natural materials and any parts of the human environment. The artist does not seek to create a finished work but tries to convey his ideas to the viewer, to involve him in some kind of intellectual game.

Furthermore, materiality needs to be discussed in relation to conceptualism. In the 1960s, the thought about the need to dematerialize art began to actively spread in developed Western countries (Smith, 2017). Its supporters urged artists to abandon the creation of classical works, such as paintings or sculptures. The only true meaning is the author’s idea, which can be conveyed to the viewer in different ways. Hence, conceptual works of art can have several specific distinctive features. One of them is the impact not on the emotional, but on the intellectual perception of the viewer. Another feature is the frequent use of explanatory text to work.

Furthermore, the artist’s conscious refusal of the importance of form in favor of the importance of the work’s meaning, and the idea is typical for conceptualism. Finally, the creation of art objects from any objects available to the author is another feature that distinguishes conceptual works. According to conceptualists, the artist has the right to decide what a work of art is, regardless of the opinions of other people.

In a way, conceptualism is a new form of a convention that decomposes all integrity as false and inorganic. A concept is an idea attached to a reality that it cannot correspond to. Hence, this incongruity to alienate causes an ironic or grotesque effect. Conceptualism plays on perverted ideas that have lost their real content, or on vulgar realities that have distorted common idea (Smith, 2017). An abstract concept is pinned to a thing like a label not to connect with it, but to demonstrate the impossibility of unity. Conceptualism is the poetics of bare concepts, self-sufficient signs, deliberately abstracted from the reality that they seem to be called upon to designate (Smith, 2017). It is the idea of schemes and stereotypes that shows the falling away of forms and substances, meanings and things. The naive, mass consciousness serves here as the subject of reflective reproduction.

Avant-Garde Movement and Performance

Avant-garde is one of the worldviews aimed at the destruction of traditional artistic laws and forms and considered more radical than modernism. The art of avant-garde is complex and contradictory since it includes a productive search for new art forms and visions of the world. Common features of the avant-garde are the atmosphere of rebellion, the guidelines for constant updating and creative experimentation, mosaicism, and outrage (Smith, 2017).

Furthermore, the modern perspective is characterized by the flow of consciousness, amoralism, the principle of destruction of the whole and installation of its fragments. Hence, the basic idea of the avant-garde is freedom from traditions and social restrictions. An irrational form of spiritual experience, such as volitional, sensory, intuitive, and subconscious, is chosen as the way of cognition of the surrounding reality. From the point of view of the avant-garde, in the process of perception, a human must rely on the original worldview, devoiding of the negative influence of civilization and cultural norms. Only by getting rid of conditional restrictions, an individual can contribute to the free creation of a new era.

Overall, the emergence of the avant-garde is due to a number of historical, political, philosophical and socio-cultural reasons. The most significant social changes in the world in the early twentieth century arose under the influence of socialist and communist theories, which were based on the idea of a radical restructuring of the world (Smith, 2017). In turn, an aspiration for social and political changes caused similar ambitions of the transformation of art.

Jiří Kovanda’s Works in the History of Art

Jiří Kovanda is one of the most iconic performance artists of the 1970s that, nonetheless, few people know about. He achieved the invisibility of his actions by reducing the visual component of the performance. Through his close attention to small details and his zealous experience, he turned the routine inside out. Considering the ideas and means of the avant-garde, the art produced by Kovanda reexamined the tendencies with its original forms. Working in Prague at times when political censorship and economic difficulties ruled the continent, he created subtle installations that could be passed by without even noticing. His performances were non-invasive and subtle, so no one around him understood what was becoming a part of them.

One or two black-and-white photographs on a sheet of paper and a couple of words of description underneath are all that have been documented from Jiri Kovanda’s performances. According to Menegoi (2007), Kovanda’s “most notable works… are a series of actions carried out from 1976 onward, in Prague or near the city, and installations realized … beginning in 1978” (para. 3). The actions of the artist presented in photographs are so simple that the viewer might wonder why one would feel the need to record and carry them out in the first place. Performances took place in public places, such as streets, squares, bridges, but they were secret in nature and not announced in any way. Only the photographer was aware of the artist’s intentions and, occasionally, a few of Kovanda’s friends were invited to watch his performance.

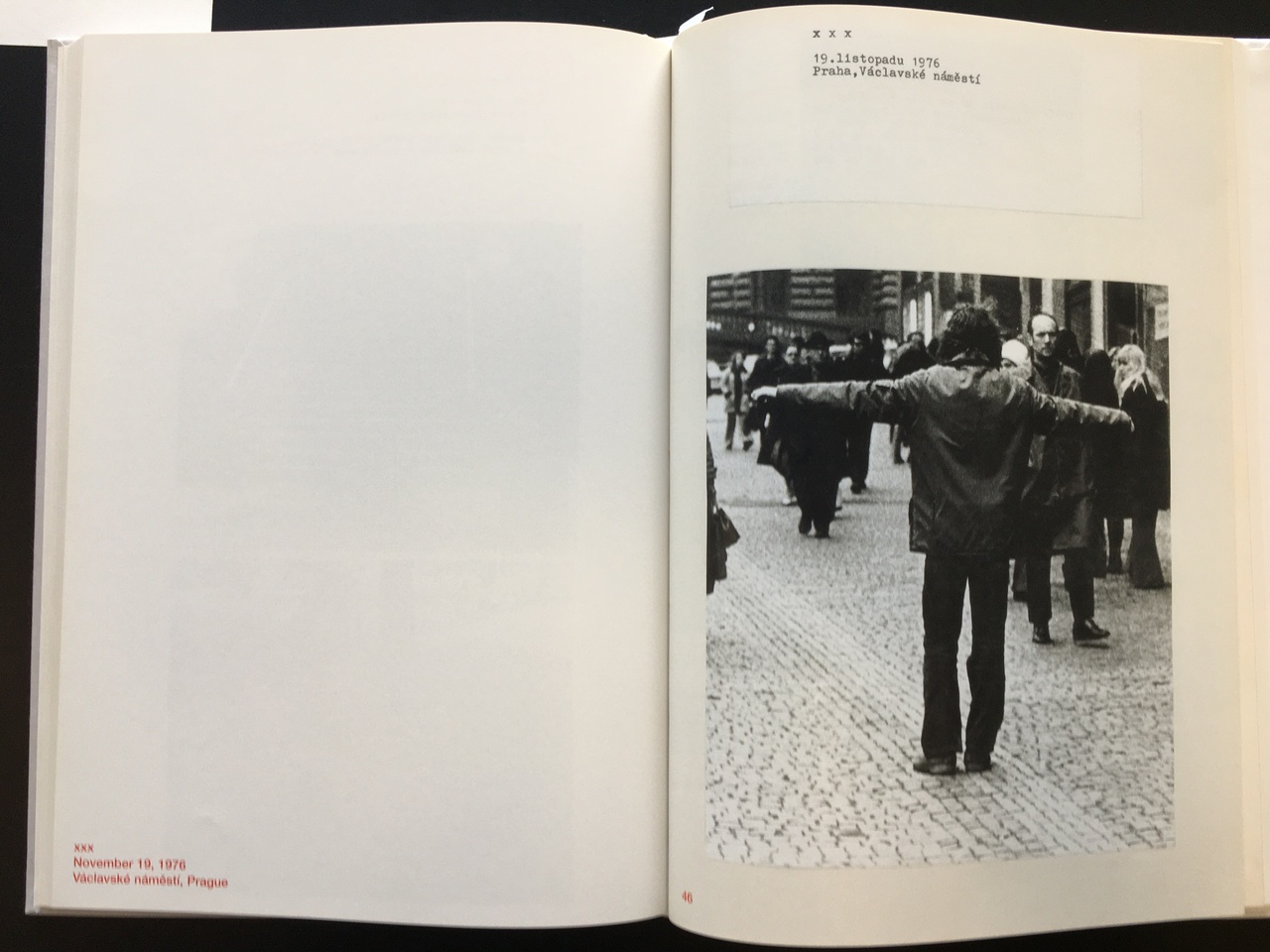

Kovanda’s attitude may appear non-professional due to his subtle way of expressing himself. At the same time, some might argue that through unspoken antics, he reacted to total control and the impossibility of an open artistic gesture. In particular, his unnamed picture presented in Appendix A is often labelled with political and protesting connotations. The figure in the photograph with arms wide open resembles the act of crucifixion.

Generally, the underground art of the Socialist Bloc is frequently interpreted as a reaction to totalitarianism. And although the Soviet situation unambiguously dictated its terms, the idea that everyone who was not a member of the artists’ union was a saboteur of the regime would be a simplification. In this regard, Kovanda’s action is aimed to rather create an obstacle to the flow, make a statement of himself, than to imitate the crucifixion. His performance depicted the physical and mental stress of the artist, bringing anxiety into the daily routine of passers-by, not a nation suffering from a repressive system (Kovanda & Havránek, 2006). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that an action in a public space always escapes from the thought and will of its author and can acquire political significance.

Many actions of Kovanda involve interactions with people, and passers-by sometimes involuntarily participate. One of the examples is Kovanda’s (1979) “Contact” that pictures the artist casually coming into contact with strangers passing by. At the same time, direct interaction with someone who walks by is clearly not the goal. Kovanda does not hesitate to highlight the impersonality and indifference of the passer-by, who, in turn, does not have the slightest idea that he has just been targeted by contemporary art. This meeting has little or no effect on them, just like hundreds of others that occur throughout the day.

With all the delicacy and contact of actions, in relation to a passer-by, such contacts are always invasive in a way because the artist without permission overcomes, along with his barriers, those of strangers. As Kovanda unintentionally pushes a person, intentionally moves in the opposite direction, behaves defiantly and looks into the eyes of a stranger, he carries out actions that cause a slight conflict with which the artist works. Nevertheless, Kovanda’s interventions have never been aggressive, and this propensity for careful interaction with the world and a minimal presence in it may have been instilled by the Prague reality of the 1970s.

The memory of the suppression of the “Prague Spring” he experienced brought up in him a desire to abandon any volitional attitude towards reality. In his works, Kovanda reaches out and clings to those passing by, but at the same time sets the framework for the action in such a way that real contact in them is impossible. He accepts the absurdity and constraint of his efforts and brings the unsuccessful communication into the artistic field.

In some of Jiri Kovanda’s works, there are spectators who know that they are watching a performance. At the same time, the artist does not say a word to them about what is going to happen now and where to look. In Kovanda’s (1977) “Attempted acquaintance,” the crowd absent-mindedly looks at the artist as he hesitates and fidgets, naively trying to get to know the girl or make sure that no one pays attention to him.

It turns out that even when Kovanda invites his friends to look at the action, he builds up the same incomplete interaction with them, and even they take the form of a faceless part of the urban landscape or home apartment. According to Kovanda and Havránek (2006), the artist conceived these micro-contacts with strangers around him as a personal practice of communication with the world, in many ways, therapeutic and rebuffing his timidity. Hence, his actionism is an expression of his own intuitive and intentionally simple approach.

For some of his works, Kovanda uses concise but prolonged descriptions. For instance, Kovanda’s (1977) work “I carry some water from the river in my cupped hands and release it a few meters downriver” seems emphatically useless and absurd by nature. At the same time, it is full of contemplation of fleetingness, tenderness, care for the urban pieces. Kovanda is somehow devotedly and ascetically obsessed with his work, namely, either the desire to help, or to explain, in short, to streamline what is happening with his irrational impulse. For all its intuitiveness, simplicity and minimalism, Kovanda’s shares are multivalued, but they do not fall apart into contradictions.

The absurdity is associated with the artist’s attitude to art as a subtle practice when the process completely outweighs the result. Here Kovanda, just as in the stories with passers-by, emphasizes the inferiority of his actual action, the result of which is only a piece of paper with a picture and a signature.

Similarly, other performances appear even more marginalized, especially while being carried out in public places. Another Kovanda’s (1977) work is self-descriptive: “XXX, I rake together some rubbish (dust, cigarette stubs etc.) with my hands and when I’ve got a pile, I scatter it all again…” The absurdity of the action aims to emphasize the author’s acceptance of senselessness of his efforts. The act is purposeful and meaningless at the same time.

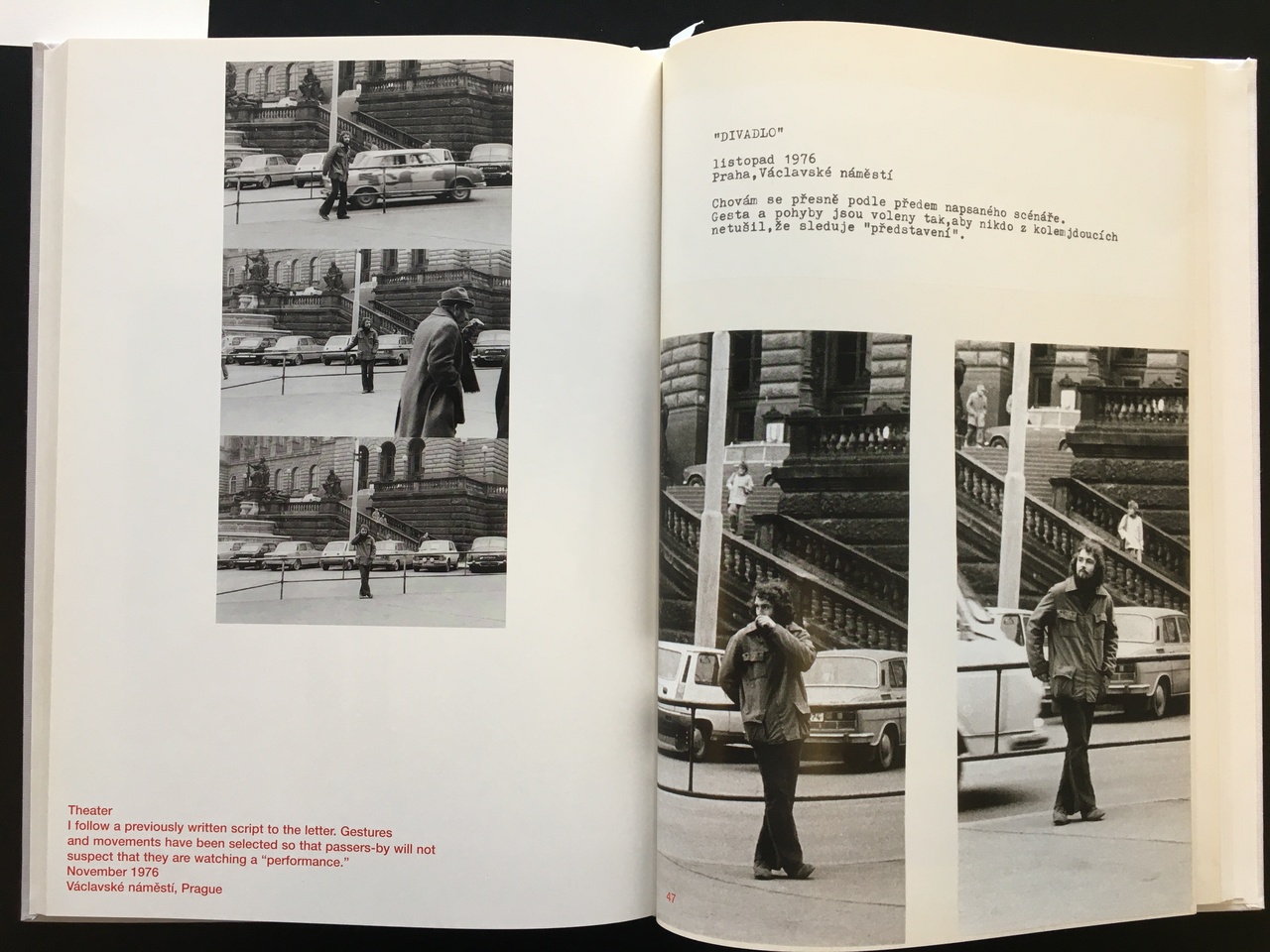

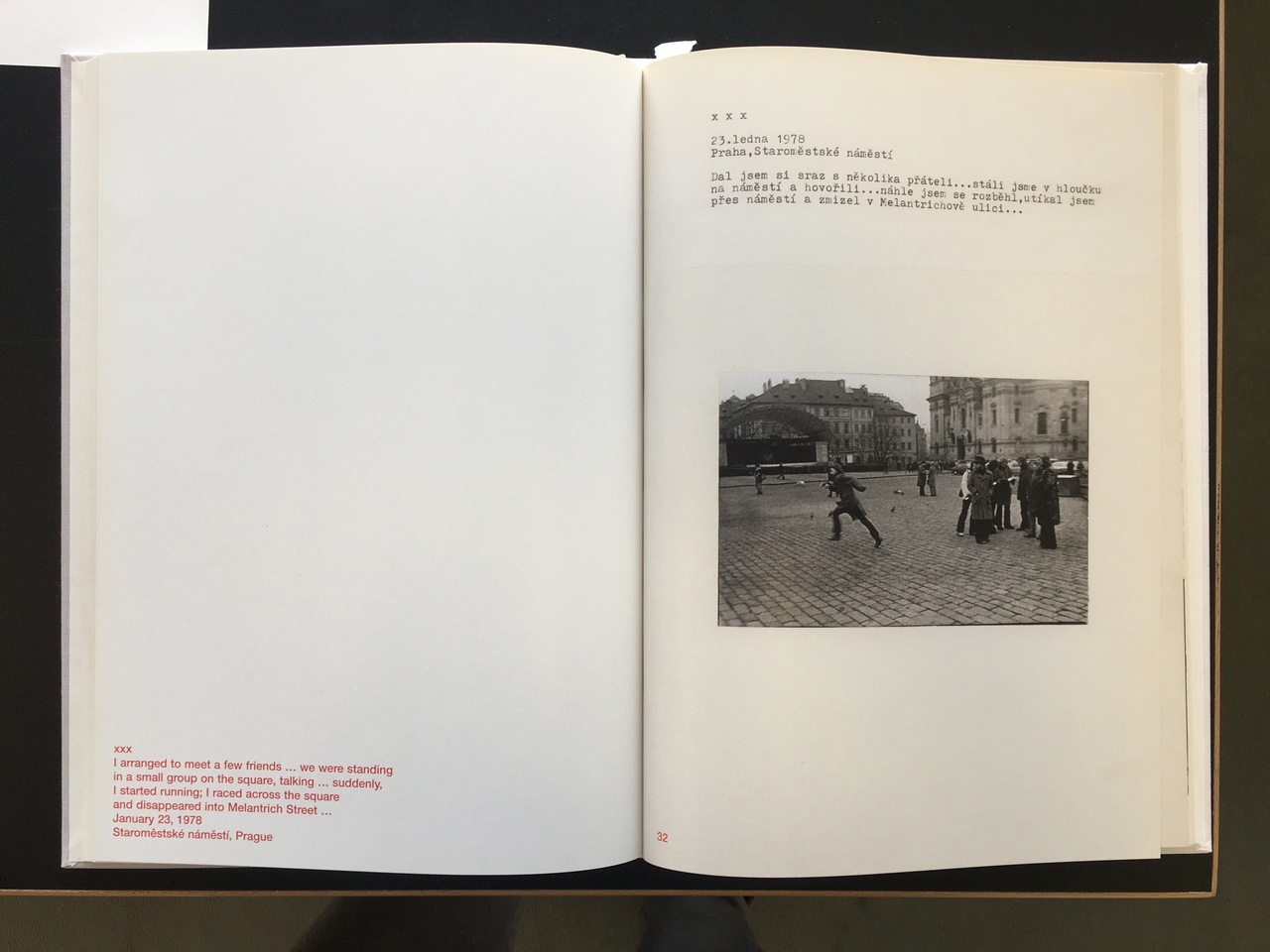

Another Kovanda’s (1976) work, “Theater,” presented in Appendix B, portrays a performance located near the theater building. The artist carries out extraordinary simple movements, such as standing on one leg, scratching his nose or leaning on the railing. Such subtle and elusive changes, in reality, blur the boundaries between art and life. Furthermore, some of the actions are intentionally shocking to the viewers who unknowingly participate. For instance, Kovanda’s (1977) work “I arranged to meet a few friends….” demonstrates how the artist suddenly interrupts a casual talk with others and rushes away across the square (as shown in Appendix C). This performance is among the most dynamic in nature, while others use less spontaneity to catch the audience’s attention.

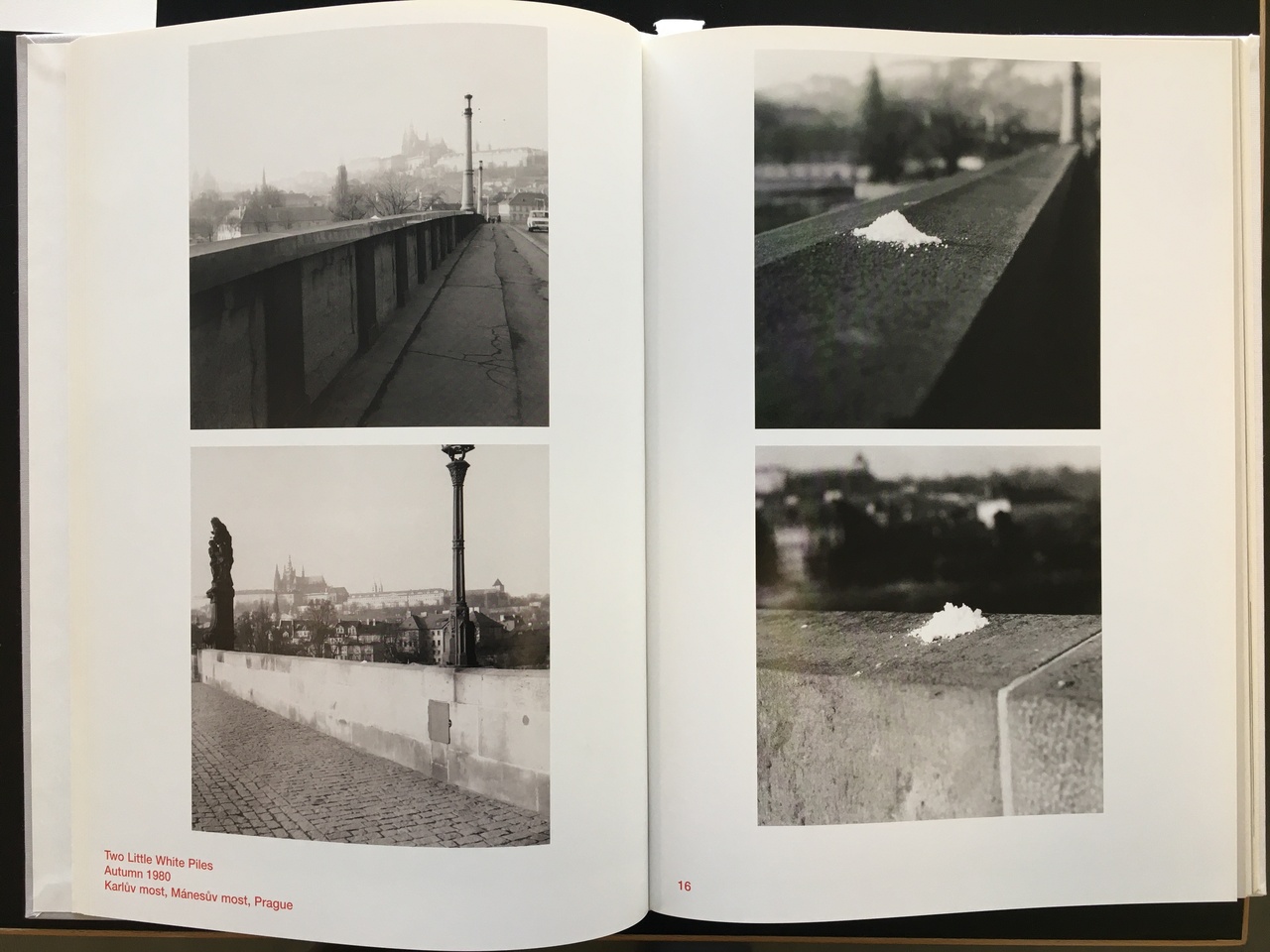

Moreover, not all the works of the 1970s-1980s feature the artist himself, and some depict objects placed in unusual surroundings. For instance, Kovanda’s (1980) photograph “Two Little White Piles” presents a handful of sugar or salt left on two parapets of bridges (as depicted in Appendix D). According to Menegoi (2007), such “installations are no less elementary than the performances, and … even more private, given that Kovanda was able to document them on his own,” without inviting a photographer (para. 5). In this regard, the artist’s abnormal behavior is more articulated than some unusual object placed in the urban environment. However, Kovanda’s perception and attitude to the world can be seen through both means of expression.

Furthermore, the descriptions are the final stage of the work for Kovanda. Like actions’ nature, their format is short, and language is minimal. They define events like art and allow them to finally come into communication with a real spectator. These small signed pictures are so cleverly arranged that they do not just give a one-sided cut of something that has already happened, but reveal the entire process of this artistic practice, this form and these fragile stories. The viewers catch the satisfaction of the frozen, elusive and emphasized invisibility.

In a way, Kovanda was an avant-garde artist, tolerated by the regime only while remaining underground. At the same time, according to Menegoi (2007), he was “isolated … from the avant-garde scene itself, … because he didn’t have artistic training and was often viewed as a dilettante” (para. 4). Furthermore, he did not share political concerns but was dominated by them in historical context. Kovanda’s reply to people asking about his actions’ influence on society was “I am not saying they weren’t influential, but … was absolutely not important for me” (as cited in Menegoi, 2007, para. 4). In this regard, it is obvious that he was not pursuing the goal to make a loud statement or challenge the politics.

The artist’s interactions with the world were related to the social context, and his rebellion was experimental. Kovanda noted that actions involving psychological tension due to shyness “constituted a violation of limits, not only in respect to the people on the street” but also himself (as cited in Menegoi, 2007, para. 7). In this regard, his actionism implied a behavior unnatural for the artist in real life. Kovanda’s performance and intervention works focus on the discovery of new types of relationships, involving his friends and anonymous passers-by.

To summarize, Kovanda’s work in the history of conceptualism can is still relevant, and his attitude and perception of the world can be considered radical despite the subtle nature of his actionism. Kovanda’s performance required close attention in order to be noticed, and his acts were society-oriented rather than political. In accordance with the principles of conceptualism, the artist relied on his own perception and means of self-expression with the world. Kovanda’s work and attitude have influenced the cultural field and constitute a reference for other artists.

References

Kovanda, J. (1977) Attempted acquaintance. I invited some friends to watch me trying to make friends with a girl [photograph]. MoMA, New York, NY, United States. Web.

Kovanda, J. (1977) I carry some water from the river in my cupped hands and release it a few meters downriver… [photograph]. MoMA, New York, NY, United States. Web.

Kovanda, J. (1977) XXX, I rake together some rubbish (dust, cigarette stubs etc.) with my hands and when I’ve got a pile, I scatter it all again… [photograph]. MoMA, New York, NY, United States. Web.

Kovanda, J. (1979) Contact [photograph]. MoMA, New York, NY, United States. Web.

Kovanda, J., & Havránek, V. (2006). Jiri Kovanda: Actions and installations 1976-2005 (Vol. 1). Tranzit.

Menegoi, S. (2007). Action! The Silent Revolution of Jiří Kovanda. Mousse Magazine. Web.

Smith, T. (2017). One and five ideas: On conceptual art and conceptualism. Duke University Press.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D