Introduction

Today, the Olympic Games play a significant role in the world of athletic competitions. With the current rapid development in science and technology, it calls for the world’s athletic body to put more effort towards the establishment of state-of-the-art stadia. One of the challenges facing the athletics body is finding the most suitable places to locate the stadia. The Bird’s Nest Olympic Stadium started operating in 2008 (Broudehoux 383-397). The stadium hosted both the Olympics and Paralympics games in 2008. Besides being the host of the Beijing Olympic Games, the stadium is also a symbolic building and acts as one of Beijing’s landmarks. The stadium is one of the breakthroughs in construction technology. It comprises unique steel structures, which allows it to enjoy the pride of being the model of the Olympic stadia (Broudehoux 399).

Nature of the stadium

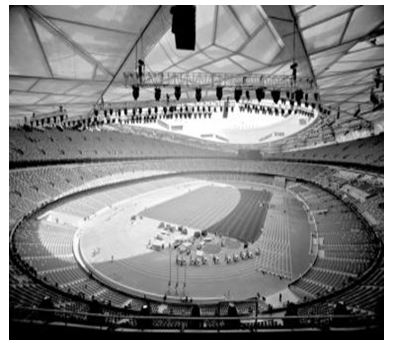

Besides athletics, the stadium also hosts other games like football and numerous ceremonies. The Bird’s Nest stadium covers an area of about 258 thousand square meters (99.614 square miles) and accommodates 80,000 permanent seats and 11,000 short-term seats. The architects used big steel frames to curve out their current appearance (Zhang and Zhao 254-254). The stadium has a saddle-shaped roof with the major axis being 332.3 meters (1,090 feet) long and the stub axis being 296.4 meters (972 feet) long. The highest point of the stadium is 68.5 meters (225 feet) above the ground and the lowest point is 42.8 meters (140 feet). The roof is covered with a transparent material, which allows sunshine to penetrate, thus facilitating lighting the stadium. In addition, the field is covered with grass that grows naturally.

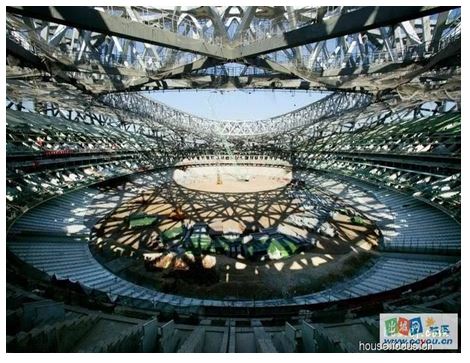

The surface of the structure might appear simple. Nevertheless, the geometry used in developing the stadium is so intricate that it was hard for the architects to do their calculations manually, and thus they had to use software for effective calculations. Without software, it would have been hard for them to ensure that the steel bars used in constructing the stadium were in line with the surface of the structure. The stadium comprises a seven-story wall made of concrete. In addition, the roof of the stadium and the steel structure are not intact (Jaeho and Jilly145-163). Nevertheless, the two share a common foundation. No matter how random the nest structure may appear, it observes all the crucial geometrical rules and comprises 36 kilometers of unpacked steel. The Chinese viewpoint of harmony and balance dubbed “yin yang” motivated the establishment of the nest structure.

Two layers of transparent ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE) and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) casing make the stadium’s roof. The ETFE covers the upper part of the roof while the PTFE covers the lower part. In addition, the inner ring’s sidewalls are enclosed in a PTFE audio ceiling. Inflated ETFE cushions cover all the spaces left in the stadium’s structure (Jinxia 2798-2820). In a bid to ensure that people enter and leave the stadium with ease, the architects installed numerous tripod barriers in all the entrances.

Background of the structural challenges

One of the major structural challenges that faced the Beijing National Stadium was in its mode of construction. The steel bars used in constructing the stadium posed a major threat to the safety of people that use the stadium for various events. The tragedy at the France airport terminal raised the issue of enhancing safety in the Beijing National Stadium (Zhong 157-159). The airport terminal was built using a design similar to what was initially scheduled to be used in constructing the Bird’s Nest stadium. Just like the airport terminal, the stadium’s roof stood with no supporting pillars. Hence, in case of occurrences like an earthquake, the roof would come down crushing everybody in the stadium. Therefore, to ensure that the stadium was secure, the architects had to come up with a new design for the stadium.

Changes made on previous design

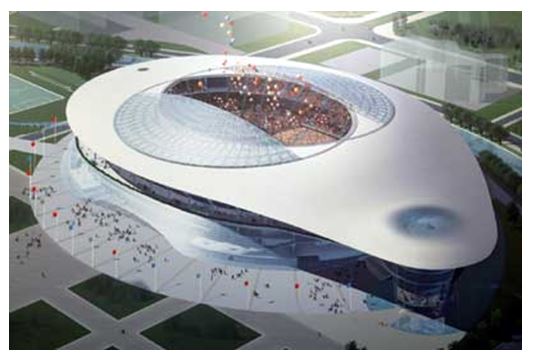

After the accident at Charles de Gaulle International Airport, the architects working on the Beijing stadium decided to reconsider their structural design. They realized that the retractable roof would make it hard to guarantee the safety of the stadium. Hence, they had to come up with a different design for the roof, which could withstand catastrophes like earthquakes. The retractable roof was the root cause for the desire to come up with a “nest” design (Jin and Bu 131-154). Nevertheless, the architects had to give safety the first precedence making it hard for them to proceed with their previous design. The new design meant that the architects would do away with the 9,000 seats accounted for in the previous design. In the process, the design helped in cutting down the cost of the project by approximately $290 million. The initial cost of the project stood at about $500 million. The removal of the retractable roof helped in reducing the weight of the building holding the stadium.

The stadium can now withstand seismic activity and to ensure that spectators enjoy watching games under all weather conditions, the architects replaced the retractable roof with a transparent material, which is waterproof and transparent to ensure that adequate light reaches the football pitch. From the outside, the stadium resembles a nest (Zhong 163-168). Hence, the stadium got the name “Bird’s Nest Stadium” from this physical appearance.

The architects intended to ensure that every spectator had an opportunity to see events in both the football pitch and the athletic tracks without any problem. Besides, they wanted to ensure that the stadium would be in a position to host numerous events apart from the Olympics and the Paralympics games. One of the challenges they encountered touched on bringing all spectators closer to the field without going out of the established budget (Zhong 170-178). Therefore, to come up with the desired design, the architects depended on design software. The software helped them to deal with challenges like ensuring that the grass in the field grows without interference, the sightlines are clear to all participants, the field can withstand seismic activities, and a good air conditioning system.

The Snow park plan

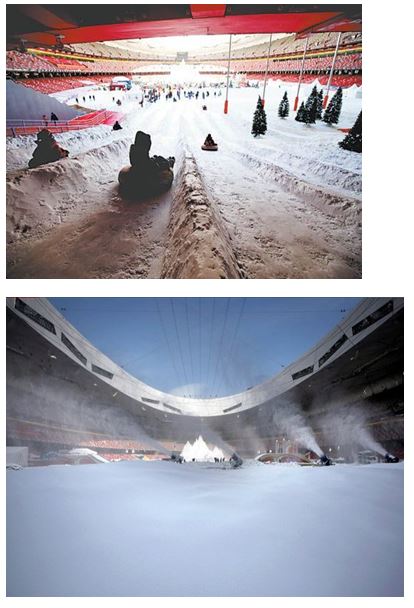

The Chinese managed to overcome the structural challenges facing the construction of the Bird’s Nest Stadium. Nevertheless, this element did not bring to an end the challenges surrounding the stadium. Today, they encounter immense challenges in their effort to maintain the stadium (Economy and Segal 47). Every time a country is hosting the Olympics games, it ends up spending a lot of money in building facilities to host the games. After the Olympics, the facilities become of less importance to the country even after spending a lot of money on construction costs. Today, many Chinese do not see the reason why the government had to spend $450 million to construct the Bird’s Nest Stadium, which was only to host the Olympics games that conventionally last for about one month.

In a bid to recover some of the money spent in constructing the stadium, the stadium’s management team opted to make some cash by using the stadium for Snow Park activities during the winter. However, the number of people using the facility proves uneconomical (Economy and Segal 49-53). Even though the strategy looked like a good idea, other expenses like water and electricity charges are inevitable, thus adding to the cost of managing the stadium. Besides, numerous drawbacks make it hard for the management to make money from this plan. The cost of a single ticket is unusually expensive thus discouraging many people from using the facility during the winter season. A ticket can go for 120 Yuan during weekdays and 180 Yuan over the weekend. Consequently, many people see the recreation activities in the stadium as expensive and thus opt to seek the service in other areas.

During the winter season, numerous skiing fields emerge in Beijing. People use some of these fields at no cost. Hence, the people prefer the fields to the stadium. With the huge costs incurred in the construction of the Beijing National Stadium, most of the Chinese see it as a possible “white elephant” (Economy and Segal 54-56). The stadium is one of the most expensive facilities that no longer serve its purpose. Besides, the country has to incur approximately $5 million annually to maintain the stadium.

Addressing the snow park problems

In the quest to minimize the cost of maintaining the Bird’s Nest Stadium, the management team should do away with the snow park project. Alternatively, to ensure that more people participate in the project, the management should come up with activities that are more attractive and give incentives to the participants. For instance, the management may award skiing suits to the participants who perform exemplarily. Besides, the management may use other incentives like lowering charges for students who wish to use the stadium. Such strategies would convince more people to use the facility thus increasing the revenue generated through the project.

How to benefit from the stadium

The Bird’s Nest stadium is one of the most fascinating facilities in the world. Many people wish to go and see the stadium because of its construction uniqueness. After the Olympics, few activities take place in the stadium, and thus the major source of revenue for the stadium is the tourists who come from different parts of the world to see the stadium. Besides the snow park program and tourism, the stadium may generate revenue in many other ways (Jinxia and Mangan 2019-2033). In Germany, after the Berlin Olympics, the Germans started using the Berlin Olympics Stadium to host other numerous activities as a way of generating revenue from the stadium. Today, they use the stadium to host football events like the 2006 FIFA World Cup. The same can apply in China.

China is known for hosting numerous big events; for instance, the country hosts the New Year show annually. The country could host the show in the stadium thus making the stadium useful. The stadium is spacious and can accommodate many people; hence, it offers an appropriate venue for hosting other activities like concerts. The auto show is another event that is popular in China. In most cases, the event is held in open places and many people grace the occasion (Jinxia and Mangan 2035-2040), which can be a good source of revenue for the country if it is hosted in the Bird’s Nest Stadium. Numerous big sports events take place in China. They include the Italian Super Cup, international friendly football matches, and championship games. Instead of holding these events in other stadiums, the country can use the opportunity to host them in the Beijing National Stadium thus helping it to generate revenue for its maintenance.

Conclusion

The Bird’s Nest Stadium played a significant role in hosting the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. Initially, the architects intended to build the stadium with a retractable roof. However, the tragedy at Charles de Gaulle International Airport in France forced the architects to change their initial design. They opted to do away with the retractable roof to enhance the stability of the stadium. They covered the roof with transparent materials in a bid to light the stadium. The main challenge facing the stadium is that after the Olympics, it hardly generates substantial revenue in spite of the cost incurred in its construction. Nevertheless, the stadium can become productive if the management decides to host most of the major events in the stadium.

References

Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. “Spectacular Beijing: The conspicuous construction of an Olympic metropolis.” Journal of Urban Affairs 29.4 (2007): 383-399. Print.

Economy, Elizabeth, and Adam Segal. “China’s Olympic nightmare: What the games mean for Beijing’s future.” Foreign Affairs 87.4 (2008): 47-56. Print.

Jaeho, Kang, and Jilly Traganou. “The Beijing national stadium as media-space.” Design and Culture 3.2 (2011): 145-163. Print.

Jin, Houzhong, and Te Bu. “Studies on Beijing Olympics game’s spiritual legacy: Brand value.” Journal of Sustainable Development 3.2 (2010): 131-154. Print.

Jinxia, Dong. “The Beijing games, national identity and modernization in China.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 27.18 (2010): 2798-2820. Print.

Jinxia, Dong, and Ja Mangan. “Beijing Olympics legacies: Certain intentions and certain and uncertain outcomes.” International Journal of the History of Sport 25.14 (2008): 2019-2040. Print.

Zhang, Li, and Simon Zhao. “City branding and the Olympic effect: A case study of Beijing.” Cities 26.5 (2009): 245-254. Print.

Zhong, Fan. “New techniques of large-span structure design for national stadium Beijing.” Engineering Mechanics 3.4 (2010): 154-178. Print.