Theoretical and Conceptual Knowledge

In the context of modern education, E-learning has become one of the important concepts drawing the attention of theorists and academics. Many educationalists have recognized e-learning as innovative method of learning, as they have evaluated its benefits over time. There are others, who criticize the process for its limitations. However, the support and adaptation of e learning is gaining increasing momentum.

Proliferation of Internet along with advancements in information and communication technology has delivered significant innovation in the delivery of higher education through e learning (Teo and Gay, 2006). This has also led to increased responsibilities on the part of different stakeholders for ensuring that there is adequate motivation and trust among all the stakeholders associated with e-learning including the students. In this context, this essay looks into the concepts of responsibility, trust and motivation as they apply to the environment of e-learning.

Responsibilities of the Online Learners and Instructors

Learning online has been proved an overwhelming task for the students who are new to the experience. Many of the students have not understood the fact that they have to alter their attitude and approach to become an online learner. The students cannot also appreciate the fact that the role of an online student differs from that of a student, who learns by direct contact with the teacher in a traditional classroom setting.

A large number of failures are noted in the e-learners because of several reasons including poor designing of the course, lack of motivation to the learners and lack of application. Nevertheless, a majority of learners fail because of the fact that they were not ready to be online learners (Piskurich, 2003). Garrison et al (2004) point out that students who are new to online learning do not comprehend the responsibilities and requirements of online learning.

The student pursuing online learning has to undertake large responsibility for understanding the whole scheme of online learning. This is because of the fact that the online learning has a different nature where face-to-face interaction is absent. This responsibility is enlarged because of the features of the medium, which entails more freedom to the learner but still confining.

It is not the adjustment in respect of technical skills that the learner must be equipped. The online learners must develop the skill of communicating and get acquaintance with the people who are associated with the online community. For the purpose, the learner may have to use a medium without any visual cues, which are possible in a face-to-face setting. The increased expectations from the learners to contribute ideas and share thoughts will enlarge the cognitive demands and this might as well change the social identity (Garrison, et al., 2004, p 64).

In order to become successful in online learning, learners have to possess a lively attitude to learning. Further Chang & Fisher (2003) suggest that students have to work in a collaborative manner to generate deeper levels of understanding. According to Zariski and Styles (2000), it is important that students should become self-directed learners, which calls for students to acquire the properties of self-regulation and they must be responsible for organizing their learning.

They also need to be reflective. It is possible for the students who become self-directed to understand the content fully and in addition, they can adopt a positive attitude for shaping themselves as learners. This will make it possible for them to reflect properly on their learning and it will act as the motivating factor for continuing the online learning throughout their lives (Clayton, 2003). Armarego and Roy (2000) state by undertaking some process of self-assessment or by generating reflective journals, students of online learning get more chances of reflection and introspection, which enable them to make sense of the experiences they have acquired. An “e-learner must be able to identify and prioritize his or her personal skill gaps” and “manage the learning experience, including setting clear goals, establishing specific plans, and securing needed resources” (Birch, 2002).

Students must understand the purpose and function of online learning in order to be successful in the e-learning environment. “This will need to be made explicit and involves giving both teachers and students time to be comfortable in using the tools provided in the online environment” (Craig et al., 2008).

The role of the instructor in any e-learning environment is to “ensure that some type of educational processes occurs amongst the learners involved” (Chang & Fisher, 2003). In the traditional face-to-face classroom environment, a teacher assumes the role of an instructor having the responsibility of imparting knowledge to students as well as advice on the ways of acquiring knowledge (Cowan, 2006). The traditional style of teaching relies on the strategies, which are expected to transmit knowledge to the learners. However, the role of teacher differs in an online teaching environment.

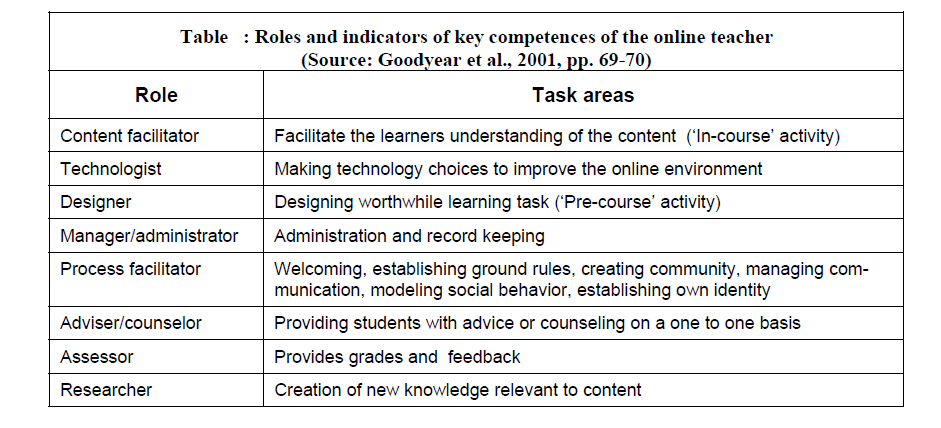

According to Salmon (2002), the role of teacher in online teaching “needs to change to match the development and potential of new online environments,” (Salmon, 2002). Teachers need to perform differently than what they have always been doing, to be successful in online teaching. In an online teaching environment, the role of the teacher becomes one of educational facilitator, which provides guidance and foster a sense of community among learners (Chang & Fisher, 2003). Cowan (2006) suggests that the online teacher must assume the combined roles of facilitator and coach and that of the moderator and tutor. Anderson (2004) observes that online teacher must be a subject matter and technician. The following table shows the roles and key competencies of the online teacher.

The role of the instructor is one, which enables students to adopt a more focused role in achieving success in online earning. Number of studies has suggested that the changes in the area have seen a shift from teacher-centered and institution-centered learning to student-centered learning. “The online teacher will therefore need to provide the discipline knowledge and the organization, design, management and sequencing of learning, as well as the social presence through online interaction” (Craig et al., 2008).

Motivation of the Learner

Under the process of e-learning, the student has to assume considerable responsibility and he has to focus closely on the process. It also requires a motivation on the part of the student for a proper e-learning to take place. In a broader context, the motivation in the context of education is defined to cover the keenness, enthusiasm and inclination of the people towards achieving some set objectives.

According to Dean (2010), for motivation to take place, the learners should develop a positive aptitude towards the subject and the determination to grasp and achieve further. In addition, the students should have the feeling that they can understand and do more. Theobald (2006) is of the opinion that students may have to depend on certain outside means for increasing their impetus. Mullamaa (2010) is of the view that in a student-centered teaching, the students should have the readiness to be independent learners and they must take the responsibility of their own learning process.

Dornyei and Otto (1998) have defined motivation as,

In a general sense, motivation can be defined as the dynamically changing cumulative arousal in a person that initiates, directs, coordinates, amplifies, terminates, and evaluates the cognitive and motor processes whereby initial wishes and desires are selected, prioritised, operationalised and (successfully or unsuccessfully) acted out. (pp. 523)

In addition to the external motivating factors, the students also need some forms of intrinsic motivation to receive and assimilate the e-learning in its proper perspective. Hasanbegovic (2005) has analyzed the influence of internal impetus on online learning. Based on her study, the author concludes “In line with the motivation theory of Ryan and Deci it is predicted and evidenced that intrinsically motivated students do more in a fixed time period as a result of their higher effort and persistence and will do different things in computer environments that allow for this liberty of choice (Hasanbegovic 2005),” (Mullamaa, 2010). Thus, most of the key aspects of learning such as “individualization, interaction, and student motivation” which are considered dominant in the concept of modern education are considered as part of e-learning process.

Dantas & Kemm (2008) are of the opinion that e-learning has been found to be specifically useful in moving learners out of the process of passing learning into a learning mode, which is highly motivated and engaging. Motivation moves upwards or downwards because of learning experiences which are either positive or negative and which act to motivate or de-motivate learners (Sakai & Kikuchi, 2009). Dornyei (2005) provides a theoretical model, which stresses the importance of self-concept of the e-learner and suggests that motivation stems from the desire to lessen the dichotomy between one’s actual self, and the self one wishes to become.”

According to Maeroff (2003), motivated students become eligible candidates for online courses. In some instances, e-learning has been found to be suitable for less-obvious students, even though such students have not taken the responsibility for learning in the traditional form of learning. Motivated learners have the chance to achieve higher levels of success. For success in any e-learning endeavor, motivation is considered as one of the important elements.

Learners, more specifically adult learners, who hold high motivational levels while learning, are expected to be more successful (Semmar, 2006). A number of researches show evidence to prove the positive association between motivation and achievements in learning. Studies have also proved that motivation has an important role to play in predictive achievement. Therefore, achievements during learning process can be considered as a valid indirect measure of motivation (Pintrich & Schunk, 1996).

In a study conducted on Web-based training, Spiros (2003) found motivation to learn was a significant predictor in respect of self-reported training outcomes. In online learning, distance learners will have a feeling of isolation and this tendency may force them to slow down or they may even terminate learning. However, motivational factors have proved to contribute for the retention of students (Kim, 2004). Xie, Debacker and Ferguson (2006) observed a positive association between participation of students in an online discussion board and the level of their intrinsic motivation. Kim (2004) found that in self-directed learning settings, lack of motivation has been one of the major causes for learner dropouts.

In addition to achievements and attritional impact, motivation is found to be responsible for many other learning effects. For instance, Klein, Noe and Wang (2006) pointed out that motivation was a significant contributor to course satisfaction and meta-cognition in addition to offering higher course grades to the learners. Brown (2005) observed motivation to be a key factor in the determination of total time spent on e-learning courses and the subsequent improvements in computer-related skills and performance. It is argued that motivation is an important driver for improved self-efficacy and self-regulated strategies.

Semmar (206) observes that successful learners are most likely to be those people “who possess a strong sense of efficacy, employ a wide range of self-regulatory strategies, and maintain high motivational levels during the course of their learning.” In this context self-regulated learning or self-regulation has been define to include “an active, constructive process whereby learners set goals for their learning and then attempt to monitor, regulate, and control their cognition, motivation, and behavior, guided and constrained by their goals and the contextual features in the environment,” (Lapan, Kardash and Turner , 2002).

Literature has equated motivation with self-efficacy and self-regulation and has pointed out that motivation is similar to the latter to the extent that motivation can have a significant effect on learning performance, is associated with cognitive and affective processes and motivation is subjected to the influence of external factors. It is observed that appropriate educational practices have the effect of improving or strengthening the motivation, which in turn results in improving online learning outcomes. Irrespective of the interaction among the elements of motivation, self-efficacy and self-regulation, they offer a valuable theoretical framework for understanding and explaining the behavior and learning performance of online learners.

Building Trust

E-learning appears to be thriving better in friendly environments, where the online community members will be able to exchange mutual knowledge. “Team working, collective learning and evolutionary developments in shared knowledge construction” helps improving e-learning practices in collaborative long-range learning projects. Learning technologists are sure to benefit by engaging themselves proactively in such team working (van Aalst, 2006). For the e-learning teams to profit from collegial participation there needs to be an atmosphere of trust. Trust implies that the input of every team member is considered valuable in undertaking constructive critical analyses of team performance without the fear of reprisals (Hoegl & Proserpio, 2004).

Kreijns, Kirschner, and Jochems (2003) argue that there is less possibility for social interaction to occur automatically in the online environment. It becomes the responsibility of the teacher to construct activities in such a way that the students can interact among themselves. It is possible to nurture trust only when learner is able to have knowledge about the co-students and the teacher by communicating with them. Before the students could collaborate with each other willingly, it is essential that they must trust each other and have a sense of belonging. It is important that the students have a feeling of oneness (Rourke, 2000).

Online students must be able to develop a feeling that the teacher and the co-students will understand their position and cooperate with them. In order to build trust the instructor must extend the contacts among them beyond normal course. It is likely that students may feel anxious and defensive in online learning environments. Further, they may be unable or unwilling to subject themselves to the exposure vital to the learning process (Kreijns et al., 2003).

It has been found that feedback is one of the essential elements in building trust and it helps in improving the connections to the institution (Lewis & Abdul-Hamid, 2006). It is a fact that students would be able to develop confidence in the face-to-face classroom environments to participate in class discussions, by comparing their performance with that of other students (An & Kim, 2006).

However, it may be difficult for the students to build trust in the online learning environment because of lack of immediate feedback and lack of cues such as facial expressions and body language. This is because of the asynchronous nature of the online courses. In the online courses, students take longer time to develop trust and confidence among their peers as compared to the time taken in classroom environments (Walther, 1992).

Communication in online learning is one of the key elements in building trust among students. It is the job of the teacher to construct the course content efficiently and provide scope for effective communication so that the learners will be attached emotionally to the online classes. “Trust building in online environments that takes place early in the semester through off-task social communication can increase feelings of trust, a sense of warmth and belonging as well as closeness among the participants” (Rourke, 2000).

It is for the instructor to set the tone of the online learning environment through the extent of support, which he will be able to provide to the students and the degree to which the instructor is engaged with the students. “The emotional context for learning is dependent on the online instructor’s understanding of how to communicate in both the cognitive and affective realms,” (Dixon, 2009). In fact, it is a challenge faced by the instructor that he will be able to meet the needs of the different types of students who enroll in online learning courses (LaPointe & Gunawardena, 2004), whom the instructor would not have met before.

In online learning courses, the instructors are faced with the necessity to motivate students without the traditional tools they use in a face-to-face classroom environment. “Limited to asynchronous, text-based communications, the instructor must learn how to convey emotion without using tone of voice, emphasis on certain words, body language, eye contact and the ability to “read” students’ reactions” (Schwartzman, 2006).

Strategy to determine the Potential for Exercising the Responsibility that E-learning demands

Institutions and individuals will choose to invest time and other resources in learning and teaching projects using technology as the base. The e-learning Maturity Model (eMM) developed by New Zealand Tertiary Institution is one of the strategic models which could help the educationalists in amending the institutional structure so that they may be able to be maintained in a position to deliver education online to as many students as possible with superior quality.

This model ensures that the institutions possess the process capabilities for improving the quality of e-learning. One of the key elements incorporated in the project is the capability of the institutions, which implies the ability of an institution to ensure that it meets the needs of the students, staff and the institution itself. The objective is that the institution must take the responsibility to support e-learning and teaching even when the demand goes up and there are changes in staff.

The processes involved in this strategy breaks down the complex role of institutions into individual areas of responsibility so that the readiness of the institutions can be assessed independently. The process categories and the brief description of the responsibilities of the institutions expected to be carried out from the processes.

The key idea is to assess the capabilities of the institutions with respect to standards established for different dimensions in respect of each of the process.

Marshall (2005) noted that

An organisation that has developed capability on all dimensions for all processes will be more capable than one that has not. Strong capability at particular dimensions that is not supported by capability at the other dimensions will not deliver the desired outcomes. Capability at dimensions one and two that is not supported by capability in the other dimensions will be ad-hoc, unsustainable and unresponsive to changing organisational and learner needs. Capability in dimensions three, four and five that is not complemented with similar strength at dimensions one and two will be unable to meet the desired goals and liable to fail. (pp 3-132)

A similar framework may be developed incorporating the responsibility and preparedness aspects from the purview of online learners for assessing their capabilities and potential for exercising responsibility for e-learning.

Research Methods and Critique

Importance of Educational Research in the Field of E-Learning and Online Teaching

For presenting a discussion on the importance of educational research in the field of e-learning and online teaching, it becomes essential to define the learning and teaching strategies. Learning strategies are those made use of by students for remembering, learning and using information. In developing learning strategies, the responsibility lies with the students.

Students undergo a process, in which they become capable of recognizing new knowledge, reviewing previous concepts, organizing and restoring previously gained knowledge and matching it with the newly acquired knowledge, assimilating it and interpreting knowledge learnt on the subject. On the other hand, teaching strategies represent the elements or features presented by the teacher to the students for facilitating a better and deeper understanding of the information.

According to Bachari et al. (2009),

The emphasis relies on the design, programming, elaboration and accomplishment of the learning content. Teaching strategies must be designed in a way that students are encouraged to observe, analyze, express an opinion, create a hypothesis, look for a solution and discover knowledge by themselves. Didactic teaching strategy for example refers to an organized and systematized sequence of activities and resources that teachers use while teaching. The main objective is to facilitate the students´ learning. (pp 510)

Within the above broad framework of learning and teaching strategies, this essay discusses the importance of educational research on online learning and teaching strategies and development of different learning and teaching practices based on the researches. With the proliferation of e-learning and increased use of online learning and teaching techniques, there is the need for extensive research in this area to evaluate and report on the developments in online teaching and learning.

With more educational and training organizations moving towards producing e-learning environments, there is the challenge of moving away from just incorporating some e-reading content towards the creation of e-learning environments. The new teaching and learning practices must be capable of recognizing the ways in which the communicative powers of Internet can create an active and supportive role for the online learners, (Albon & Trinidad, 2002; Oliver & Omari, 1999; Salmon, 2000).

Institutions imparting higher education have adopted more and more of online education. Number of research studies has focused on promoting effective pedagogical strategies, which help in improving online teaching. According to Partlow and Gibbs (2003), constructivist principles, when followed in designing the online courses will be “relevant, interactive, project-based and collaborative.” Such online courses will provide the learners with many choices for the learners and provide them control over what they learn online. Keeton in his study evaluated effective online instructional practices.

A framework of effective teaching practices followed in face-to-face classroom was the basis for the online instructional policies evolved by Keeton. Faculty of postsecondary institutions interviewed in the study of Keeton gave the highest ratings to the instructional strategies developed. They were of the opinion that the strategies “create an environment that supports and encourages inquiry,” “broaden the learner’s experience of the subject matter,” and “elicit active and critical reflection by learners on their growing experience base” (Keeton, 2004).

Bonk in his study observed that only between 23 and 45 percent of online instructors, who participated in the survey, have actually made use of online activities of “critical and creative thinking hands-on performances, interactive labs, data analysis, and scientific simulations.” However, 40 percent of the people who participated in the survey were of the opinion that such online activities are important in the process of online learning and they need to be used more in online learning environments (Bonk, 2001). From the study, it appears that there is a significant gap existing between the preferred and actual online instructional practices.

E-learning Strategies and Models

Number of researchers has analyzed and generated several e-learning strategies and models, comprising of different learning styles. There are differences in the individual learning styles and these differences have become the subject of discussion and development in the realm of education. Pittman et al (2006) have observed that individual learning styles would have an influence on the preference of students on the contents of the online courses as well as in a face-to-face classroom environment.

However, there are no adequate researches conducted to prove this hypothesis. However, many of the educators have suggested the significance of interaction in the online education to make the course of a high quality. Franklin and Peat (2001) are of the opinion that Web based education is the online education, which enables new activities in both teaching and learning. In addition, Web-based learning takes those new activities to a much high level in many significant ways as compared to previous methods of teaching and learning. This helps in creating long-lasting innovations in the society (Franklin and Peat 2001). Study conducted by Tesone et al., (2008) has found that on a comparison between online learning and face-to-face learning, students prefer a mix of both the methods.

The learning performance of students is improved when they take vigorous participation in extending their understanding and in assessing their own skills to learn. “Environments, in which students develop models, collect data and evaluate alternative designs, help them to develop vital skills. Various learning strategies have been analyzed by the educational researchers to develop the learner’s skills” (Dekson & Suresh, 2010). The following section discusses some of the learning strategies, which researchers have analyzed.

Inquiry-based learning developed by Edelson (2001) has gained prominence in science education. This learning strategy helps students to engage themselves in activities that replicate scientific investigation. This strategy has greater utility when it has its content addressed in the context of inquiry. Another strategy is problem-based learning. In this strategy, students attempt to solve the problems on a collaborative way and they reflect on their experiences.

When this strategy is adopted, the students automatically assimilate the knowledge as to how to analyze the given problem among themselves and in this they can bring their classroom knowledge into practice (Halizah and Ishak, 2008). Folashade and Akinyemi (2009) have observed that problem-based learning strategy could expose students to the realities of life. It enables them to work with the attitude of a scientist and acquire knowledge on their own.

When the innovations in knowledge as they are applied to e-learning are combined with the available human resources, technologies and software tools, it enables the learners to share and create new knowledge. This helps the learners to lay their stamp on the learning culture, which is more “learner-centered, project-based, integrated,” (Qinglong and Chengyang, 2008). “The ways of doing and approaching projects those are shared at a significant level among the learners leads to better knowledge and providing creative forms that the collaborators to accomplish new projects” (Dekson & Suresh, 2010).

Mind map is another learning strategy in which information is represented graphically, making use of keywords, links and key images. This allows large volume of information in a page. Mind map works on a non-linear way where the brain works the way mind map works (Hanan and Khairuddin, 2007).

Ubiquitous learning is one of the emerging research topics in the area of online education. This learning strategy allows the students to learn anywhere and at any point of time. In the ubiquitous learning strategy, adaptivity and personalization issues have a prominent role to play. These features enable the learners to learn in a more personalized way and whenever they want and at time convenient for them. This learning strategy considers the situation, characteristics and needs and preferences of the learners (Graf and Kinshuk, 2008). Bomsdorf (2005) dealt with ubiquitous learning and evolved the first principles of ‘plasticity of digital learning spaces’. Under these principles, the learning environments can be achieved in different contexts and situations.

The objective of blended learning is to achieve optimal level of learning objectives. This strategy is adopted through the application of right learning technologies to match the appropriate personal learning style. This is done to for the transfer of the skill to the appropriate persona at the right time (Singh and Reed 2001).

The recent innovations in information and communication technology have provided for the extension of mobile services with the facility of connecting the Internet to PDAs and mobile phones. However, these innovations have not been found to be of use in the realm of education. Alimadhi (2002) argued about the necessity of providing connections between web resources and mobile technology.

The study by Alimadhi (2002) suggested a prototype, which could look into the chances of making existing web resources connectible to mobile technology. Topland (2002) studied the challenges involved in the development of multi-channel e-learning services that can be made available through Internet, in which the content is made to be present at the same node. This study found that the browsers or devices used by the old system did not support the newly innovated multi-channel services.

The work of Avenoglu (2005) proposed the use of mobile learning portals for enabling the students to assimilate web-based instructions. The latest work of Stieglitz et al (2007) prescribed the application of a mobile e-learning network. This system operates on a completely decentralized manner using an ad hoc architecture network.

Course Management Systems

During the last decade, there has been heavy investment in course management systems (CMS) by higher education. The objective of the development of CMS is to serve as the teaching environment for the online distance education (Morgan & Schlais, 2005). Under CMS, it is possible for the students to log into the course at any time. The course materials will be made available continuously to the students. In CMS arrangement, the software has a major role to play in deciding the functionality as well as the look and feel of the online course environment. For example, this can be observed in the software ‘Blackboard’.

When a course is taught online, it has the facility of allowing the participation of the students who are engaged in full-time work. “A course taught entirely online allows the participation of students who work full-time, live far away from campus, or simply prefer to learn at home. Faculty members are often encouraged to teach online courses or to blend online instruction with face-to-face classroom instruction,” (Dixon, 2009). From the perspective of a university administrator, the online instruction system has a real advantage in that it makes it easier to enroll more number of students without having to provide more brick and mortar classrooms to accommodate the additional students (Bonk & Dennen, 2003).

Online Courses

Prior research shows that experienced professors, who have never undertaken teaching in an online course, become fascinated with the idea of online teaching, when the enlarged demand for online learning corresponds with the adoption by the university of course managements systems, which makes providing web-based instructions easier than in the case of face-to-face classroom environment (Bonk and Graham, 2006).

However, according to Sawyer (2000) the instructors are confronted with the challenges of the “multiple levels of complexity” in the learning environments, when they attempt to provide web-based instructions for an existing course. “They are learning that trying to create an online course by doing a one-to-one translation of materials from one teaching medium to another is not adequate” (Dixon, 2009).

Even though CMS can be of help to the instructors to manage more online learners, they have to adopt new and varied strategies for teaching online, as compared to those required for teaching in face-to-face classes. Typical and traditional forms of teaching such as “lectures, discussions and printed hand-outs” do not anymore find a place in the online courses. Instead these traditional teaching methods have been replaced by “text-based asynchronous” communications which enhance the participation of the online students. In a recent survey on the factors responsible and significant for success in online teaching, the need for online pedagogy for the instructors has been found to have more importance than the need for technical expertise on the part of the online instructors (Bonk & Kim, 2006).

Malilkowski, Thompson and Theis (2007) have worked on a model underlying the research on course management system and their work is based on five different categories of requirements the course has to meet. They are (i) transmitting course content, (ii) evaluating students, (iii) evaluating courses and instructors, (iv) creating class discussions and (v) creating computer-based instruction. According to the observations made by the study, the online education institutions commonly used CMS for disseminating the details of the course. Such transmission includes the syllabus, readings and assignments.

“A second most used form of transmitted content was announcements created within the CMS, followed by the built-in grade book, which are built in within the systems. Two of the categories moderately used were evaluating students through online quizzes and creating class interactions through discussion boards. The CMS was rarely used to evaluate course and instructors or for computer based instruction” (Dixon, 2009).

West, Waddoups and Graham (2007) examined faculty adoption and implementation of features from the software. The study observed that the coordinators have used all the elements of a course management system only sparingly. Instead, the instructors selected a single feature at a time and made a reevaluation of the use of the features one-by-one. In this process, the instructors experienced challenges associated with technical or pedagogical aspects. Some of the instructors found the tool handy for supporting various teaching strategies. Depending on the extent to which the instructors were successful in overcoming the challenges of implementation, they selected to adopt one of the following ways. They are

- to make use of the tool or any of its components,

- to reduce the usage of the tool or decrease the type of components used or

- discontinue using the tool altogether and use some alternative methods.

Dixon (2009) states

Ely (1999) found eight conditions that contributed to instructors’ successful implementation of educational technology: dissatisfaction with the status quo, existence of knowledge and skills, availability of resources, availability of time to learn the technology, existence of rewards or incentives to try it, participation in deciding how to implement the technology, commitment to the process, and continuing support from the leadership that showed enthusiasm for the work at hand. (pp 1)

Plan for Encouraging Research on Education

Abel (2005) has prescribed the factors responsible for success in Internet-supported learning. These include the need for institutions to “nurture grassroots faculty ideas, clearly communicate about the online process and support faculty with technology and pedagogy”. Involving faculty, in the creation of best practices beginning with a well-designed educational philosophy and learning model will facilitate the implementation of these key elements.

These models should focus “on developing scholar-practitioners through learning and relevant experience.” Almala (2007) has reinforced the significance of these key drivers for improving the quality of e-learning experiences. The author emphasized that “strong pillars for building a quality e-learning environment need to be in place before implementing successful and quality e-learning courses and programs” (p.26). Some of the key drivers included “planning, providing user-friendly technology-driven delivery systems and creating and maintaining a robust e-learning infrastructure.”

Creation and maintenance of robust e-learning infrastructure requires enhancing the knowledge of the online instructors continuously so that their knowledge is up to date and can help enhance quality of e-learning. Without enhancing their knowledge and skills, the instructors would become out of date very fast, given the rapid development of technological development and its influence in updating the online learning and teaching environment. This calls for encouraging the educators and instructors to undertake research in education on a continuous basis so that they can keep their knowledge gap filled.

Research on education can take place in any area connected with pedagogy or blending technology updates with the online teaching methods. The research can also extend to areas of online teaching that covers “faculty orientation, creating social communities, learning facilitation, motivation enhancement, improving interaction, feedback strategies, assessment and evaluation.” Continuous research in these areas will help the educators to evolve best practices in the field of online teaching and learning.

The plan for encouraging research by online educators must include the factors of reward and recognition apart from providing the necessary support to them by the distance education institution. Rewards and recognition may be monetary or in the form of commendations broadcasted online to the associated communities, which will act as an intrinsic motivation for the instructors and other educators to pursue research on a continuous basis. Research findings used to adopt best practices in online teaching or other administrative areas may be documented and circulated among others for pursuing further research in the area.

There are several qualitative research methods like case study and focus group interviews available for doing research on any topic online education. However, the faculty undertaking the research must possess excellent technical knowledge so that the best practices developed may be adopted using any of the advanced technological aids. The focus on incorporating best practices in the online teaching environment is to recognize the importance of building and communicating professional expertise. Professional expertise can be enhanced by undertaking knowledge building exercises through research or by communicating within the faculty, which would help bridging theory and professional application. The following are some of the strategies recommended for improving the professional expertise.

Irlbeck (2008) has recommended

- Creating an environment to encourage development of scholar-practitioner model

- Maintain flexibility and responsiveness to various learning styles

- Demonstrate competence in the professional discipline as evidenced by current or continuing education, research, publications, continuing practitioner experience and consulting in the field

- Demonstrate ongoing professional development (pp 26).

All the above strategies clearly point out the need for the online educators to sharpen their skills by enhancing their knowledge for which undertaking research is one of the most convenient and purposeful factor. Through research on various connected areas, the online faculty would be able to not only enhance their knowledge and skill but also improve the quality of online learning by the students. This can ensure excellence in the performance of the online education institution, by incorporating best practices in the online learning as well as teaching environments.

Professional Application

Copyright Issues

Intellectual property (IP) covers different types of legal monopolies. These monopolies cover both artistic and commercial creations of mind and the respective fields of law. Under the legal provisions governing intellectual properties, the owners are entitled to some rights, which are exclusive to them. These rights are applied in relation to a number of intangible assets like musical and literary works. Intellectual property rights are granted in different forms such as copyrights, patents, trademarks and so on. A copyright is the protection applied to a term expressing the idea rather than the concept thereof. There is a distinction between copyright and patent in that copyright applies to the protection of expression and patent is concerned with the protection of ideas.

Definition of Copyright

“A copyright is a property right attached to an original work of art or literature. It grants the author or creator exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute, adapt, perform, or display the protected work. Other than someone to whom the author/creator has extended all or part of these rights, no one else may use, copy, or alter the work” (Newsome, 1997). The owner of a copyright may claim and recover compensation by bringing an action in a court of law, from any person indulges in wrongful use of the copyrighted materials. The owner of a copyright gets a right of control over all forms of reproduction. “A copyright gives the author or owner the right of control over all forms of reproduction, including photocopies, slides, recordings on cassettes and videotapes, compact disks, and other digital formats” (Newsome, 1997).

Traditionally copyright protection used to be granted based on specific application of individuals. However, works created since the year 1978 automatically became entitled for copyright protection, once the work takes a tangible form. This protection is made available to the work irrespective of the fact of whether a copyright notice is attached to the work or whether the individual has made a specific application for copyright protection with the Copyright Office of the United States. “For works created and published before 1978, copyright lasts 75 years from the time of publication or copyright renewal” (Newsome, 1997).

It must be noted that copyright protection does cover the particular expressions or words the creator has used for presenting an idea, but not the underlying concept or idea. “To qualify for copyright protection , the work must be (a) original, (b) creative to a minimal degree, and (c) in a fixed or tangible form of expression” (Newsome, 1997). In general, the copyright law covers the following categories of work.

Talab (1986) has categorized

- literary works – both fiction and nonfiction, including books, periodicals, manuscripts, computer programs, manuals, phonorecords, film, audiotapes, and computer disks

- musical works — and accompanying words — songs, operas, and musical plays

- dramatic works — including music – plays and dramatic readings

- pantomimed and choreographed works

- pictorial, graphics, and sculptural works — final and applied arts, photographs, prints and art reproductions, maps, globes, charts, technical drawings, diagrams, and models

- motion pictures and audiovisual works – slide/tape, multimedia presentations, filmstrips, films, and videos

- sound recordings and records – tapes, cassettes, and computer disks (p. 6).

It is possible to use a copyrighted material under certain conditions.

Newsome (1997) summarizes these conditions as

A copyrighted work may be used or copied under certain conditions : public domain – work belonging to the public as a whole-government documents and works, works with an expired copyright or no existing protection, and works published over 75 years ago; permission – prior approval for the proposed use by the copyright owner; legal exception – use constitutes an exemption to copyright protection-parody, for example; or fair use – use for educational purposes according to certain restrictions. (pp.1)

The fair use enables teachers to have access copyrighted works for uses beyond in classrooms or textbooks. It can also enhance and enrich learning opportunities for students.

Definition of Fair Use

The fair use principle underlying the copyright materials enable the pubic to copy works, without seeking permission from the owner of the copyrighted material or pay any licensing fee to the owner. However, there does not exist a single test for determining the “fair use” of a copyrighted material. It therefore becomes important that to treated each case differently based on respective circumstances of the individual cases, as the courts may interpret each case differently based on the associated circumstances. “Court rulings have generally given more leeway to uses that are for academic purposes, especially if revenues are not part of the instructional artifact” (Rajarathnam, 2010). Fair use entitles the use of copyright protected works for restricted use of research or commentary without getting the permission from the owner of copyright.

An author can use a copyrighted material in the form of references without any licensing requirements, when such reproduction is tested for the presence of the four elements discussed earlier. “Fair use is based on free speech rights provided by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution” (Rajarathnam, 2010). There are some frequent misconceptions about the span of fair use concept. These are:

- Use of copyrighted material always requires the permission of the original holder of the right

- Material which is not copyrighted is in the public domain and can be used freely

- A mere acknowledgement in the new work is sufficient to denote the fair use of the copyrighted material

- A person can avoid the repercussions of copyright infringement if he/she does not use exact words from the original work

- A person can plagiarize a work which is not protected under copyright law

- All non-commercial use of the copyrighted material will be treated as fair use.

Fair Use and Teachers

“Fair use explicitly allows use of copyrighted materials for educational purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research.” The following are the four determinants prescribed by the copyright law for identifying the fair use of copyrighted materials. These provisions are contained in Section 107 of the United States Copyright Act, 1976 (Fair use in Copyright, 2001) and these factors should be considered for determining whether a particular action is “fair use.”

According to Princeton University report,

- Purpose of use: Copying and using selected parts of copyrighted works for specific educational purposes qualifies as fair use, especially if the copies are made spontaneously, are used temporarily, and are not part of an anthology.

- Nature of the work: For copying paragraphs from a copyrighted source, fair use easily applies. For copying a chapter, fair use may be questionable.

- Proportion/extent of the material used: Duplicating excerpts that are short in relation to the entire copyrighted work or segments that do not reflect the “essence” of the work is usually considered fair use.

- The effect on marketability: If there will be no reduction in sales because of copying or distribution, the fair use exemption is likely to apply. This is the most important of the four tests for fair use.

It must be noted that none of the above factors could constitute fair us on its own. Even though copyrighted materials can be copied for educational purposes, it is essential that the use meet with the other standards prescribed. In the issue of copyright relating to online education and teaching, there have been no specific regulations covering web-based delivery of course materials developed so far.

Even though these issues have remained unresolved, they cannot be ignored by the educators and instructional designers, who are involved in the creation of web-based courses. Until such time specific legislation is passed in this respect, the wisest course of action for the teachers and educators to pursue fair use or follow the guidelines for fair use, while dealing with Internet based copyright ad intellectual property right issues. It must also be remembered that one cannot claim his lack of knowledge of legal provisions as an excuse for not following them. The following are some of the important issues, which need the consideration of teachers.

- In one instance, a teacher has been found guilty of copying 11 pages out of 24 pages of an instructional book. The teacher was found guilty, since the book was used in subsequent semesters without obtaining prior approval from the copyright holder (Washington State University, 1997).

- The courts have prescribed severe penalties for violation of copyrights or infringement. Courts can provide for monetary penalties to the extent of $ 100,000 for the use of copyrighted materials without owner’s permission (University of Texas)

- Many government and private organizations have prescribed policies governing the adoption of materials protected by copyrights. If a teacher disregards the copyright policies prescribed by the school district or the institution with respect to copyright, he/she cannot expect to obtain any support from the employer, if the teacher is found guilty of misusing any copyrighted material.

Challenges for Educators

The issue of copyright and intellectual property rights, in web-based course design appears to be complicated. There important issues connected with the application of copyright law to the web-based teaching courses, which require careful consideration. Traditionally, teachers have been using copyrighted materials for teaching in the classroom. The private space of the classroom has made the extension of copyright law difficult.

Consequently, it has not been possible to detect and prosecute the teachers for any type of infringement of copyrighted materials. However, in an online classroom environment, there is a potential chance that non-students can have access to the materials. Such non-students can copy, reproduce or otherwise manipulate in such a way, which is not possible when the students reproduce the material in a classroom environment.

Where multimedia technology is made use of in education, the potential publication of the work by students incorporating copyrighted materials is an issue connected with the copyright use. Public nature of material posted on the Internet, because of its public nature is also at the center of the discussion. Internet is a public forum, which provides access to educators to meet different educational uses. Nevertheless, there has been no clear delineation of the fair use of copyrighted materials in an online learning environment.

The issues of copyright remained unresolved in the discussions between “authors, publishers, journalists and news media organizations and academic institutions.” There have been some attempts to address the issues connected with the fair use of copyrighted materials, undertaken with the objective of applying the existing copyright laws to publishing using available technological media such as web page content. In the Conference on Fair Use (CONFU), held in Washington D.C. in May 1997, attempts were made to reach a consensus among different stakeholders about the fair use of the copyrighted materials and the application of copyright to specific situations. However, no agreement could be reached at the Conference.

The guidelines suggested at the Conference include a specific section dealing with the use of multimedia programs and projects for educational and other purposes. The issue of “asynchronous computer mediated delivery of distance education”, which is a significant one in online teaching environment has been completely omitted to be discussed in the Conference.

Thus, emerging technologies have brought different challenges to the present day’s teachers. Despite the challenges, the teachers can have ready access to great pool of information and knowledge because of the presence of Internet and through developments in computing technology. “Newer technologies also allow teachers to transfer, copy, and digitize learning materials faster and easier than ever” (Newsome, 1997). It is also possible to transfer the digitized information to longer distances quickly and without leaving a trial. The work of the teachers are made easier as they can copy text and images instantly and then save them easily in the computer (Carter, 1996).

In this complex environment, the teachers cannot really judge, to what extent they can use other peoples work. “The law may seem confusing, ambiguous, and unclear. At the same time, the massive amount of information and images greatly diminishes the likelihood of exposure if works are copied illegally” (Newsome, 1997). Nevertheless, the implementation of legislation covering copyright has not received much recognition. “While education institutions have begun to protect themselves from liability, some teachers, either from a false sense of security or lack of awareness, engage in illegal use or retention of materials” (Chase).

Another issue in the context is one relating to intellectual property of the course designer. It is important that the contract between the institutions and the course designer specifically address the ownership of a course in a web-based format. The public nature of the online course materials makes this issue specific to the web-based courses. According to Meyen et al., (1998), “All of the knowledge and skills the faculty teaches online become open to review. Although it may be restricted to students, it is still public. This is in contrast to traditional courses, where lectures are presented but not recorded.” (p. 53). The authors are of the opinion that public nature of online course materials is likely to have implications on the evaluation of the instructor.

The Defense of Fair Use

The following section discusses the factors that the courts will look into for judging the fair use of copyrighted materials.

Transformative use – Objective and Character

The Supreme Court of United States focused on this factor in a case decided by it in 1994, as the key determinant for establishing fair use. The issue pertains to whether a person has used the copyrighted material to create an entirely new work or the work has just been copied verbatim for using elsewhere. For example, a person creating a parody makes a transformation of the original work by making it the subject for ridiculing. The court will view purposes like scholarly use or educational purposes as transformative uses, because the work involved is mostly in the nature reviewing or commenting on the original work.

Nature of the Copyrighted Work

When the copyright involves dissemination of facts or information to the benefit of public, copying works like biographies will be categorized as fair use by the courts. When the copying is done from a published work, there are more chances of the courts considering as fair use than the unpublished works. In the works, which are not yet published the author still can change his expression before it is released in public domain.

Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Copied

It is possible that when a small part of the work is duplicated that the courts may take a lenient view with respect to infringement. On the other hand, when the little part duplicated represents the “heart” of the main work, the fair use defense may not work. However, this rule does not apply in the case of parody work, where the court has taken a different view. In the case of Campbell v Acuff-Rose Music, 510 U.S. 569 (1994), the Supreme Court observed, “the heart is also what most readily conjures up the [original] for parody, and it is the heart at which parody takes aim.”

Effect of Use upon the Potential Market

While the factors like the nature, purpose and character of use and extent of the work copied are the factors that need to be weighed for determining the potential infringement, the adverse impact on the market of the copyrighted work is the most important factor to be considered.

This factor takes into account the other three factors and the effect of these factors on the market potential of the copyrighted work. Uses that have no or little effect on the market will qualify for fair use defense. The case of Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301 (2d Cir. 1992) provides an example for this case. In this case the court ruled that “it did not matter whether the photographer had considered making sculptures; what mattered was that a potential market for sculptures of the photograph existed.” Therefore, depriving a copyright owner of substantial income will remove the character of free use from the copying act.

Examples of Fair use

Classroom handouts constitute copyright materials requiring permission in some cases for the defense of fair use. “If the handout is a new work for which you could not reasonably be expected to obtain permission in a timely manner and the decision to use the work was spontaneous, you may use that work without obtaining permission. However, if the handout is planned in advance, repeated from semester to semester, or involves works that have existed long enough that one could reasonably be expected to obtain copyright permission in advance, you must obtain copyright permission to use the work” (Copyright Clearance Center, 2005).

“All articles, chapters and other individual works in any print or electronic course pack require copyright permission.” The permission for course pack is usually granted per academic year basis. If the course pack is to be used for the subsequent years there is the need to obtain permission each year it is used. In addition, the following have been ruled as fair use by the courts.

U.S Government (2009) in its notification has prescribed that quotation of excerpts in a review or criticism for purposes of illustration or comment; quotation of short passages in a scholarly or technical work, for illustration or clarification of the author’s observations; use in a parody of some of the content of the work parodied; summary of an address or article, with brief quotations, in a news report; reproduction by a library of a portion of a work to replace part of a damaged copy; reproduction by a teacher or student of a small part of a work to illustrate a lesson; reproduction of a work in legislative or judicial proceedings or reports; incidental and fortuitous reproduction, in a newsreel or broadcast, of a work located in the scene of an event being reported.

Professional Development Strategy

Beyond the question of legal responsibility, there is the ethical issue, which the teachers should consider in the matter of using other people’s works. Teachers should undertake a ethical responsibility and apply principles of honesty and dependability in this regard. Therefore the professional development strategy and plan for educating teachers on fair use must insist on teachers to protect themselves from legal liability and also provide a model to students as to when and what works can be copied for educational purposes. The strategy to implement the plan for proper use of other people’s works, there are three questions, which the teacher should consider before using or copying copyrighted materials for educational purposes.

- Will the teacher use the expression by the author or creator in the way, in which the words or expressions are sequenced in the original work? When the teacher answers this question in negative, then the use of the work will constitute fair use. It must be remembered that photocopying or duplicating the other people’s work is the same thing as using the words or expression of the author. When the teacher answers this question in the affirmative or if there is any doubt, then it is necessary to consider the following question.

- Is the work covered under copyright protection? When the teacher answers this question in negative, then the use of the work will constitute fair use. For example, the teacher is free to use works, which have become part of the public domain because they were created long before or remain unprotected because of any other cause. When the teacher answers this question in the affirmative or if there is any doubt, then it is necessary to consider the following question.

- Will the use cross the boundaries of fair use? If the proposed use falls under any of the exclusions stated above, then the teacher is free to use the work. However, the teacher has to consider the limitations applicable to the fair use factors.

If the teacher’s answers to all the abovementioned questions are in the affirmative, then the teacher can use the work only after obtaining express approval of the original creator of the work entitled to the copyright. If the teacher’s answer to any one of the abovementioned question is in the negative, then the activity shall constitute fair use.

Ethical Considerations

Online learning has invited people, who were earlier limited by various social and economic elements to pursue their educational opportunities (Althauser & Matuga, 1998). However, the freedom attached to online earning has given rise to new ethical dilemmas, which need to be addressed. There are issues connected with ownership of electronic materials, monitoring of online content, individual rights and institutional responsibilities. I, as a distance education administrator considered it important that a comprehensive policy for my organization in respect of the ethical issues concerning the online learning environment is developed, so that the learners, instructors, administrators and the institution is aware of their roles and responsibilities from an ethical perspective.

Ownership of Electronic Materials

Ownership of online course materials can be subject to a number of complicating factors. Determining ownership of online course materials has to consider the institutional philosophy, the possibilities created by the digital media, legal issues including copyright and other practical issues involved. The starting point for determining the ownership is to define what constitutes a course. Faculty members might have developed much of the course materials.

Other materials may be copyrighted by others, yet can be used under the principles of fair use or under other available exceptions under copyright law. There will be no issues when the materials are used in a traditional on-site class. However, there may arise many issues when the course is developed with the intention of distributing it over the Web or for using the course for profit. The policy of the institution with respect to intellectual property must specify types of activities covered by the institution.

It is necessary to consider the provisions of copyright law while framing the policies. “Owners can be individuals, teams, or organizations. “Increasingly online courses are developed by teams of individuals – faculty, technologists, instructional designers, graphic artists and perhaps students. All those who contribute to the final product may have a claim to some legal rights in the work,” (Peterson, 2003).

The CETUS consortium for higher education activities has suggested three factors that could determine the rights of faculty and institutions to a particular work. They are

- creative initiative,

- control and

- investment.

Development of a copyright ownership policy must incorporate the interests of all the stakeholders involved and the policy development process should be fair to all concerned. Since faculty is the most affected by the institutional policies, it is advisable to have a dominant representation by the faculty.

The institutional policy must cover the components of

- intellectual property policies covering patents, copyrights and trademarks

- copyright policies,

- policies for ownership of software and

- policies for ownership of course materials.

Monitoring Online Content

The ethical principles for teachers are developed by the Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. These principles cover the ethical value of competence in content and pedagogy. In online learning, instructors require technological competence to enhance their pedagogical competence. McLeod (2007) observes, “as students’ impatience with their instructors’ technological obtuseness increases, college and universities need to have some honest and open discussion about their ethical obligations to meet technology-related instructional needs and interests.”

Because of the increased use of Internet and digital technology in the online learning environment, holders of copyrighted materials have to take necessary precautions to safeguard their intellectual property rights (Odabasi, 2003). There are several ethical problems, which may arise when preparing and using online course materials.

McMohan (2007) has identified the following ethical issues in this connection.

- Course integrity problem (course approval and revision needed for quality control)

- Advising problem (if information on the web does not match the catalog, this is an ethical problem of misrepresentation)

- Intellectual property problem and academic freedom (syllabi reflect the personalities of the instructors, when a faculty changes a course content, who owns the property is an ethical debate*. If you are an employee of the institution then the institution owns the property since you are hired and paid. On many campuses in the US, content belongs to the instructors, syllabi to the institution)

- Succession planning problem (who is to monitor the original course integrity while preparing the online interpretation?) (pp 211-212).

Individual Rights and Responsibilities

There is very little known about the impact of cultural differences in online learning. It is not possible to judge whether people know more or less comfortable and they have understood the concepts, as they are not judged based on their appearance or speech (Mallen, Vogel & Rochlen, 2005). Research focused on the experiences of people with disabilities has revealed that there are potential chances for the occurrence of miscommunication in the online environment. “Managing this methodological change required a meticulous attention to detail where additional questions and clarification were offered to reduce ambiguity and improve specificity” (Bowker & Tuffin, 2004).

Therefore, it becomes important to identify and document the individual rights and responsibilities in the form of a policy statement so that everyone connected with the institution understands issues in the same perspective.

There are questions associated with the personal identity and confidentiality. Lawson (2004) observed that people feel violated when someone steals and uses their online identity. There are no established principles governing the ethical implications, when an individual has assumed an alternate persona and thus has harmed the other people on a mental, emotional or professional basis through posting information assuming an alternate persona. This has given rise to greater importance for establishing ethical standards in respect of roles and responsibilities of individuals.

The ethical requirements for online instructors include providing clear instructions to students and expectations from them concerning attendance and grading policies, assignments and projects, rubrics for valuation and expected timelines. Person teaching in an online environment must model effective communication skills and he/she has to maintain records of applicable communications with students and administrative staff of the institution.

The instructor has to provide timely and constructive feedback to students on their submission of assignments and other course materials. There must be continuous monitoring and reporting on the work of the student work and a consistent assessment of the progress made by the students. It is the responsibility of the online instructors to ensure appropriately maintained and secure learning environment. Such learning environment should be productive and ensure safe learning for the students. The instructor should have the ability of demonstrating sensitivity to cultural differences and should be able to deal with varied opinions and personalities while teaching online.

The activities provided by the teacher should meet the needs and expectations of and be relevant to all students. The online teacher should be ready to inform students of their rights to privacy and he/she should be considerate of the time and place limitations of the students throughout the continuance of the course. The online teacher should establish high moral standards for the students to follow and develop the moral standards for the students to exhibit high levels of honesty and fairness in using the online facilities including Internet.

It is important that the online instructor update course content and varies activity types periodically so that the content can be kept fresh and current.

Haughey argues that using codified solutions will not be able to find suitable solutions to ethical problems in educational settings. This is because students normally do not accept their responsibility to an extent that goes beyond their self interest while undertaking a course. It is therefore for the institutions and instructors to determine their own ethical responsibilities in the design and course offering of the distance education program. The instructors and the institutions, while deciding on their responsibilities have to consider the contexts in which the students find themselves and they must be fair regarding the course load and performance of the students. The students must be made aware of the expectations from them even at the beginning of the course. The evaluation by the students of the performance of the instructors is also important.

Hartman and Steflkovich (2005) have identified the following principles as code of instructional ethics for the administrators of distant education institutions.

According to Evin (2007),

- Making the well-being of students, the fundamental value for all decision making

- Honesty and integrity for fulfilling professional responsibilities

- Protecting civil and human rights of all individuals

- Obeying the local, state and national laws

- Implementing the administrative rules and regulations of the affiliated institution

- Pursuing appropriate measures to correct regulations that aren’t in conformity with sound educational goals

- Avoiding use of position for personal gains

- Accepting the academic degrees of the accredited institutions only

- Maintaining standards and making research for continuing professional development

- Honoring all contracts until fulfillment or release (pp 111-112).

Institutional Responsibilities

According to Frankena (1986) proposed that an institution needs to address three ethical questions in the matter of ethical issues concerning online learning environments. “

- What should our laws require, forbid or permit?

- What should our positive social morality require, forbid or permit?

- What should be the rules and ideals of other social institutions?”

The institutions must keep issues relating to personal ethical standards outside the purview of the institutional policies. The challenge for online education institutions is to distinguish between the issues that could be permitted within the institutions and those, which should not be permitted. At the same time the institutions should consider and support the rights of individuals to assert their own ethical beliefs.

There are instances in online education, where the instructors and students have their own responsibilities to meet in respect of ethical considerations. For instance, when professors share information about a student, who uses any electronic media, the professors have the responsibility to appraise the student, in case the student claims access to the information. However, when two students have discussion about a professor through e-mail, the professor has no similar right.

Carlson (2001) observed that the professor gets the right to access the information from the student, when the student posts false and damaging information about the professor and such information have to be posted in a forum accessible by members belonging to the online learning community. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the decision of the Fourth Circuit Appeal Court in supporting the right of a university administrator “to prohibit employees, including faculty from viewing sexually explicit material” available on the Internet, without the express permission of the supervisor (Foster, 2001).

Each of the institution has been made responsible for framing its own core intellectual property policy.

On the IP policy Rudestam & Schoenholtz-Read, (2009) Stated Within the institution, this policy extends to ownership of a distance learning course, the rights of faculty and students within that course or seminar, access rights to the seminar, potential liability for the institution and the faculty associated with the course and accreditation and international policy implications as the participants are located globally (pp 53).

The institutions have the responsibility to provide the information to the learners repeatedly, as this is critical for ensuring their understanding and cooperation. The institution must spell out everything concerning the ways to use discussion boards, the ways in which the instructor would deal with plagiarism and the ways in which the instructor can be contacted in the syllabi and Websites. According to Gearhart it is a continuous process to keep the policy of an institution ethical and current.

Policy Document

This document describes the ABC Distance Education Center’s policies and associated institutional procedures covering the provision of distance education through online.

Code of Principles for the Institution

- The institution will give ample prior notice for any course or program proposed to be offered. The notice will cover a formal plan that describes the “objectives, content, criteria for evaluation, nature of student work, basic bibliography, calendar of activities, and types of support to be given to individual students, requirements for a diploma or certificate”. The institution will also notify whether such a diploma or certificate carries official accreditation and authority by whom the recognition was granted

- The institution will “use as the authors of courses, teaching assistants, and all those who will participate in the teaching/learning process and have contact with students, individuals of proven competency and probity,” (Litto, 2000).

- The institution will uphold legally valid agreements specifying the duties and responsibilities of each party. The contracts will cover the engagement of teachers, instructors, and educational advisors

- The institution will protect the freedom of expression of the instructors and students. It will not involve itself in any kind of ideological, political, religious censorship. It will not also create any conditions for the manifestation of varied tendencies of social or scientific perspectives. The institution will offer their teachers and instructors a freehand to choose the appropriate approaches and procedures for fitting the content of the course.

- The institution will make available human resources and material infrastructure adequate to the number and type of students enrolled to the courses offered by it

- The institution will not divulge any private information about its students and instructors. It will also avoid providing personal details of individuals to others.

Material Content of the Course

- The institution will attempt to use the pedagogical strategy centered in the student and his/her needs. The content and strategies will not be centered in the instructor

- The institution will adequately convey the requirements for joining to its classes

- The institution will systematically accompany the progress of each student. This will be done through tutorials, didactic support and counseling. The institution will also motivate each student to complete the entire program of studies with the best results achievable

- The institution will assure that all learning procedures employed in the courses are the latest ones

- The institution will distinguish course content, teaching and promotion materials and marketing by using different techniques and methods

- The institution will refrain from using any presentation of information, which is changed electronically with intention, in both their teaching and advertisement materials. This is to enable students to refrain from arriving at erroneous conclusions. When there is the intention to avoid false representations, tags or indicators will be used. These indicators may contain warnings such as “simulation,” “digitally reconstructed image,” or “digitally altered information.”

Monitoring the Content of the Course

- The institution will undertake a continuous evaluation of the materials used in its study programs. This evaluation will provide special attention to the following aspects. Litto (2000) states that the evaluation will relate to

- the academic content and the level of the approach to it;

- the methodological and pedagogical goals;

- the adaptation of the material for the type of students enrolled;

- the linguistic aspects of the material used;

- the appropriateness of the media chosen for use;

- the considerations of democratic access to knowledge, of special needs, and questions of gender, ethnicity and social class (pp 1)

- The institution will “offer to authors, teaching assistants and consultants that orientation and training appropriate to the operations and pedagogical specificities of DL, so as to guarantee quality in their work” (Litto, 2000).