Abstract

Parenting is a noble task, but one that comes with a number of challenges. Every parent often wants the best for his or her child, but not all of them are able to do this. In this study, the primary aim of the researcher is to investigate and report the lived experiences of the Native American mothers who are living off the reservations. Current studies show that Native American women currently prefer parenting their children off reservations because of their lived experiences in these camps. The review of literature reveals that the historical trauma that these parents had while living in these reservations, especially the discrimination by the Whites affected their affection towards people around them, including their children. The literature also reveals that most of these parents prefer raising their children of these reservations so that they can have better experiences and ability to integrate with other Americans as they grow. Defining the methodology used in the study is very important, and this is explained in chapter three. It looks at how data will be collected and analyzed to make a meaningful conclusion. Instruments of data collection and analysis and issues about ethics and validity of the study are also looked at in this chapter.

Literature Review

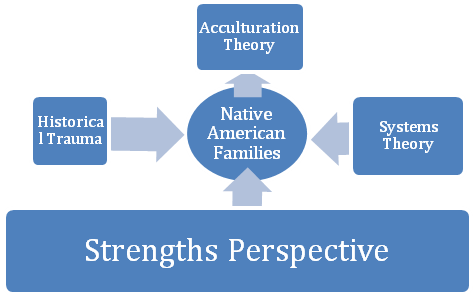

Parenting styles vary all over the world. There are culturally divergent philosophies on child-rearing and all of them are influenced by tradition as well as the current factors that prevail in the external environment. This chapter will explore the background of Native American women and factors that may be influential in their child-rearing practices. The chapter will anchor the research on a conceptual framework based on the theories of historical trauma, systems theory, acculturation theory, and other relevant concepts. This review of literature will attempt to give a chronicle of the lives of the Native American families to understand how the contemporary Native American woman has evolved with regards to raising her children.

This chapter will also highlight some issues of Native American women and the challenges they encounter as they raise their children outside the boundaries of the Native American reservation and in mainstream society. A literature review was conducted using several sources of information. The research strategy began with EBSCO databases on the Walden Library website, which was then followed by Google Scholar. Original search terms were Native American women and minority parenting. Secondary search terms included; but are not limited to, Native Americans, culture, parenting, minorities, education, Crow Reservation of Montana, Native Americans living both on and off a Reservation, phenomenological research Some advanced searches were done with combinations of some of the primary terms, i.e. Native American parenting and history Crow reservation. The literature review revealed that there are few studies outlining the parenting styles of Native American women residing off the Reservation

Historical Background

Native American culture possesses positive values and traditions such as strong respect for elders, community and their beliefs regarding the sacredness of the conjugal relationship. Such values have made their society stable through their history (Wilcox & Kline, 2013). When such values are strengthened, the people remain resilient against threats to the dissolution of their dignity as an ethnic group such as high violence rates, suicide and substance abuse (Alden, Lowdermilk, Cashion, & Perry, 2014). Native American cultural bonds have been severed by the forced institutionalization of thousands of Native American children into boarding schools and indoctrination into the Caucasian culture (Turansky & Miller, 2012). Consequently, the Native American people lost their resilience, resulting in higher rates of substance abuse, violent victimization, and teenage pregnancies (Kail & Cavanaugh, 2013). There was, likewise, a high rate of suicide incidences, depression, and anxiety among the Native American Indians (Wilcox & Kline, 2013).

Conceptual Framework

Historical Trauma

Native Americans have been historically traumatized due to their negative experiences of being ousted and relocated from their homeland throughout history. Unlike personal trauma, their people’s historical trauma is focused on their collective trauma as families, and this trauma has been passed on and even amplified from one generation to the next (Turansky & Miller, 2012). Collective trauma affects both the people’s collective and personal identity formation and relationship patterns in successive generations (Wilcox & Kline, 2013). For example, Kail and Cavanaugh (2013) claimed that child-rearing practices in Native American families have not evolved much. There is still prevalent neglect of children and dysfunctional families that may create a strong impact in the growth of children. These children may interpret their parents’ noninterference in their developing adolescent problems as apathy, but parents may just be perpetuating the child-rearing strategies they have been exposed to when they were much younger. Experiencing the trauma of their people is a justification for some parents in the development of dysfunction in their families (Badinter & Hunter, 2011).

Native American descendants are usually born into circumstances that are not favorable to their ideal growth and development (Druckerman, 2012). Historically, their fate was seized by the government and mandated their removal from their families, with the goal of sending them off to much better conditions. The 1900s marked the mass migration of Native American children to boarding schools where they were to adopt mainstream American behaviors. These children were subjected to torturous punishments, isolation, abuse, and neglect (Stange, Oyster, & Sloan, 2011). Most of them were transferred to foster care and were adopted by Caucasian families, forcing them to lose their adaptive Native American heritage and embrace a culture that was hostile to their race (Badinter & Hunter, 2011).

Turansky and Miller (2012) chronicled the saga of Native American children from the time of forced removal from their families due to the belief that the home environments on the Native American reservations were unfit for child-rearing. Native American parents and elders were deemed as negligent and abusive and unable to provide for the basic needs of their children because they were destitute themselves. Native American mothers were declared to have poor mothering and domestic skills, and the fact that there were a significant number of young, unmarried Native American mothers exacerbated the situation, validating the policy of having Native American children reared in proper boarding schools or by their adoptive Caucasian families.

The relocation of Native Americans, as mandated by the government acts, had a great impact on their self-sustainability. The industrialization of America caused the concentration of wealth in cities and off the Indian reservations, leaving the reservations in great poverty. Turansky and Miller (2012) concluded that the cumulative degenerative conditions of the Native American families, their culture, economy, and social networks represent the generations of collective, traumatic experiences of their people, leaving residual effects on the present generations. These dire experiences suffered jointly by these people have created a historical trauma that has significantly affected the Native Americans for many generations (Druckerman, 2012).

Systems Theory

Another theory that can explain the Native American historical trauma is the systems theory. It theorizes that each member in the Native American family system plays a role that contributes to the synchronized functioning of the system (Badinter & Hunter, 2011). Each member keeps his or her role, so children who have imbibed the part in a relationship pattern will likewise form similar relationships with others who can operate within the same family system (Druckerman, 2012). Hence, if traumatic experiences altered family relationship roles, then it may also negatively influence the succeeding relationship patterns. For example, if a boy grows up being accustomed to his parents being intoxicated most of the time, and he is being left in the care of his grandparents, then he may follow the same modelled pattern when he grows up. Alcoholism is being accepted as a way of life, and parenting responsibilities are being left to the grandparents. Studies of Yoshida and Busby (2011) found that an individual’s view of his parents’ marital quality, relationship quality with each parent, and the impact of his family of origin on himself can predict his marital stability and satisfaction in life.

The systems theory, which supports the intergenerational transmission of historical trauma, likewise suggests that an individual’s perceived impact of his family of origin moderates the quality of his later relationship patterns (Seshadri & Rao, 2012). Weak parent-child relationships due to parental silence on their traumatic histories arrests bonding between parents and children and make them feel ashamed of their heritage (Becker & Shell, 2011).

Acculturation Theory

When people are uprooted from their native culture and transported into a new one, they undergo acculturation or adaptation to the new culture. Sax (2015) theorized that immigrants first assimilate the language and behaviours of the people in the host culture, and this is followed by structural assimilation. Structural assimilation involves the social and economic integration into the new culture. Finally, some immigrants get to the last stage of assimilation that makes them identify with the new culture and abandon their identification with their culture of origin. Gordon suggested that assimilation may negatively impact more first-generation adult immigrants than their children who are born into the new culture. He also enumerated the components of language, behaviour, and identity as indices of acculturation. he Cultural identity of individuals caught between two cultures is measured in some ways by acculturation and ethnic identity experts (Thomas, Goff, Trevathan, & Thomas, 2013). Two components of cultural identity are self-designation as a group member of one culture and positive feelings for such identity as a group member (Feinstein, 2012).

Over time, it is likely that an acculturation gap grows between children and parents of immigrant families, with the parents holding onto their traditional culture and the children acculturating to the new culture (Seshadri & Rao, 2012). Children have less difficulty picking up the new language and learning the traditions and cultural behaviors of the people in the new culture. Consequently, their culture of origin, being less exposed to them, diminishes in terms of the effect on their growth and development, unless their parents consistently push it on them (Bond, 2012). For acculturation theory to apply to Native American families, it must be taken in the context of those who were relocated from their places of origin or from the reservation they had come from and how they adjust to their new homes outside the reservation.

This can lead to the cultural discontinuity when at home and in school. In extreme cases, Native American children are asked to choose between their native heritage and school success, and such dilemmas lead to disastrous effects (Feinstein, 2012). Problems like drug and alcohol abuse ensue, due to unresolved internal conflicts coming from teachers pressuring students to give up their native culture or at the least, not acknowledge it. In an attempt to reduce high dropout rates of Native American youths, it is important that teaching methods and school curricula be adjusted to mitigate cultural conflicts between home and school (Sax, 2015).

Strengths Perspective

In a study by Mileviciute, Trujillo, Gray, and Scott, (2013), it was found that the way people explain their state of life reflects their outlook and disposition. They concluded that the relationship between one’s negative life experiences and manifested depressive symptoms depends strongly on one’s explanatory style. More positive youths were resilient to depressive effects of their previous experiences. To overcome the negative experiences people have withstood in life, their competencies, resilience, resources, and protective factors that lead to positive developmental outcomes need stressing (Sax, 2015). The strengths perspective is a theory that purports to assist people identifying, securing, and sustaining their internal and external resources to help them achieve their goals and establish mutually enriching relationships with the community (Seshadri & Rao, 2012). Enriching relationships is achieved by strengthening the existing assets and facilitating the development of new resources to accomplish pre-established goals (McMahon, Kenyon, & Carter, 2013).

Native American Families

Reports from the PBS series Kail and Cavanaugh (2013) claim that Native American families are more likely to live in poverty and their children are more likely to drop out of school, have involvement in drug and alcohol abuse, have teenage pregnancies, and experience violence as compared to other cultural groups. Several of these children are supported by only one parent or are raised by their grandparents. Due to the prevalence of teenage pregnancies, the Native American families are younger, with about 34% of the population being under 18, and the median age of Native Americans is 28.7 years old. The white population’s average age is 10 years older (Druckerman, 2012). High relationship quality, measured by how stable and satisfying a couple’s relationship is, has become a protective factor for psychological well-being not only of the couple but also their children (Seshadri & Rao, 2012). On the other hand, low relationship quality may lead to negative outcomes such as high rates of substance abuse, suicide, and violence both in the general population and among the Native Americans.

Native American families value the significance of the extended family system, especially in supporting children. Grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and other relations or clan members normally take part in the upbringing of the Native American children in the reservation (Badinter & Hunter, 2011). Thus, children raised in the reservation grow accustomed to such care and guardianship wherever they go. However, once family units relocate outside the reservation, they miss out on the extended family support systems of their home communities. When they encounter problems due to lack of education, training, and employment, they are forced to turn to social services agencies that may not provide the same personal care and assistance that they are used to.

Grandparents have been increasingly relied upon to be caregivers for their grandchildren while their adult children go away to work or as custodial caregivers if the parents have lost their custody due to neglect or substance abuse (Bond, 2012). In Native American culture, grandparents are regarded as conduits of tribal cultural values and present knowledge to the younger generation (Feinstein, 2012). Apache grandmothers, in particular, actively preserve their customs, beliefs, and traditions in their cultural history and pass it on to their grandchildren. They enjoy an elevated status as agents of cultural transmission and socialization (Bond, 2012). However, the influences of media have undermined Apache grandmothers’ passing of the torch to the younger generations. Time spent educating the young ones on Native American traditions have been replaced by watching television, listening to popular music, or being involved in social networks (Sax, 2015).

Native American Children and Youth

Russell, Crockett, and Chao (2011) recount that in most of the Native American tribes and cultures studied child-rearing methods promote the culture’s survival. Infants and toddlers are being exposed to several cultural activities in Native American life. These cultural activities are carried on by older children and adults who model the same to younger children assumed to take over these roles in the future. The continuation of the cycle greatly depends on the effective transfer of traditional heritage from the older to the younger generations, as well as the skills required to keep the tribe surviving despite the life’s challenges.

The deterioration of Native American cultures resulting from the cultural challenges brought on by Western influence has affected the child-rearing practices of parents. Dealing with the actual physical displacement from their homes on the reservations and the emerging Anglo-cultural values and clamour for material comforts, Native American parents are caught between traditional child-rearing practices believed to have developmental purposes for the children and the new lifestyle changes necessitating the satisfaction of daily needs that often conflict with the tradition (Edgerley, 2011). In some tribes, traditional tribal ways have been successfully retained, despite some severe economic changes, and child-rearing has remained relatively smooth. However, in most other tribes, changes brought about by relocation have drastically transformed the usually peaceful child-rearing ways. The few adolescents who remained on the reservation are being abandoned by parents who seek employments off the reservation. Parents come back as failures, turn to alcohol, and become indifferent to their previous roles as caregivers to their children. In such cases, adolescent development becomes adversely affected (Bond, 2012).

The rate of enrollment of Native American children has significantly increased at present with around 92% attending school. However, it does not necessarily follow that all these children graduate from high school. Although graduation rates have also improved from the past, it still does not measure up to the numbers of graduates of White Americans and Asians. Dropout rates remain high (about 3 out of every 10) for Native Americans, whether in urban areas or some reservations. O’Gorman and Oliver (2012) encouraged teachers to get to know and interact with their students and customize their curriculum to meet all the students’ needs. Teachers need to understand where each of their students come from and make the effort to study their cultural attitudes and beliefs so they can incorporate these into their curriculum. That way, the children feel that they are being valued regardless of their cultural background and become proud of their cultural heritage instead of represses it (Golding & Hughes, 2012). When cultural understanding and positive school environment is being achieved, student resiliency and achievement follows (Turansky & Miller, 2012). This implies that opportunities to participate in activities and programs encouraging one’s own cultural practices, native language, and cultural arts, to name a few, should abound in schools (O’Gorman & Oliver, 2012).

According to Chua (2011), the inconsistencies of teachers and school authorities in addressing the cultural expectations in the curriculum are worrying. Children are placed in ambivalent positions when they are asked to choose between their Native American heritage and schooling. They realize the great dilemma when they choose to propagate the practices of their heritage because this causes them to fall behind in school and eventually drop out. On the other hand, if they abandon their heritage and choose to adopt the culture of their new environment, they suffer from guilt and psychological problems because their people become offended. Being shunned by their families and tribesmen makes these people turn to drugs and alcohol abuse. Bailey (2012) also noted the same thing with Native American children adopted by white families. Their prolonged separation from their people, even with brief intermittent visits, makes them feel different and alone in their situation. They cannot claim to be either White or Native American, which translates to not belonging to any specific culture completely. They are more likely to develop psychotic depression, serious mental illness, and suicidal tendencies than their counterparts who never left the reservation (Chua, 2011).

Tribal community members were open enough to discuss the challenges and problems encountered by the Native American youths in their reservation community. One problem identified was depression, which brought about academic underachievement, substance abuse, and conduct/oppositional behavior. Another was hopelessness manifested by sadness, apathy, suicidal thoughts, low self-esteem, and low initiative (Mileviciute et al., 2013). In another study, the Native American youth in the Northern Plains reservation generally reflected a positive disposition about their personal lives and identified more strengths despite the challenges they face in their communities (McMahon et al., 2013). The positive disposition was quite surprising, considering their lives of adverse circumstances. Findings of the study showed that these youths were embedded with a variety of adaptive developmental assets to cope with their dire situation and helped them develop resiliency (McMahon et al., 2013).

The concern of tribal leaders of Native American communities with child development being a key to tribal survival has moved them to action. They advocate parents to be more active in their children’s education. One tribe has started the tradition of giving recognition rewards for academic success as well as the provision of travel experiences to motivate the children to study better. In tribes where arts and crafts are specializations, programs to engage younger children in Native American arts and craft are offered to nurture their artistic talents. Providing such opportunities to small children somehow cushions them from the difficulties of adolescent growth and development (Turansky & Miller, 2012).

Native American Women

Flake (2015) argue that traditionally, Native American women’s identity and role as caretakers and culture bearers were all based on the principles of spirituality, extended family, and tribe. Because of their association with food and its supply, the women gained power and status, and it increased with age and wisdom. Native women are revered for their views on sacred matters, herbal medicines, and tribal history. However, in contemporary times, such heightened reverence for women has immensely decreased. The Native American woman has earned the reputation of being inadequate mothers. The unmarried Indian mother was usually convinced to give up her child for adoption. In a context of being given a choice, and the consideration of the possibility that the baby will have a better life with another family, the mother agrees. The child will be with parents who have the resources to provide for him or her (Huston & Howard, 2011). The Indian Adoption Project (IAP) was considered successful in recruiting unmarried Indian mothers to relinquish their unborn babies for adoption. The maternity homes provided increased social services, such as allowing them to live in maternity homes while awaiting the birth of the children, instead of staying on in the reservation (Turansky & Miller, 2012).

Native American women are more likely to suffer violent crimes, as domestic violence and abuse are very rampant in their culture. In a study by O’Gorman and Oliver (2012), the Native American women participants all reported to being exposed to several social problems while growing up in the reservation. It is because of such exposure that they become desensitized to a variety of attitudes, situations, and issues that would be considered by non-Native girls in mainstream society to be insurmountable issues. Their early exposure to alcohol abuse, child abuse, neglect, and sexual abuse, legal disputes of parents and relatives, and teenage pregnancies made them immune and desensitized so that these are not considered deviant behaviors anymore. It is not different in schools. There, they enter a world of people whose values may be different from theirs. They encounter uncaring teachers, low expectations of their skills and knowledge, insensitivity, and abuse. The low expectations of their skills conflicts with high expectations of handling adult responsibilities inappropriate for them because they are far beyond their chronological years (Flake, 2015).

Native American minority groups in the country have the highest birth rate compared to other ethnic groups. Most of them live in poverty at a much higher rate than their Caucasian counterparts. It is worse for women because they are being discriminated against in the workplaces. Native American women get jobs, if at all, that pay very low because the majority of them do not possess the skills and education for higher paying jobs. To illustrate, for each 59 cents the average Caucasian women earn Native American women earn 17 cents for the same job. Findings show that Native American women had the lowest percentage of employment in the workforce with only 35% of them employed. Add to that, 25% of Native American families have single mothers as heads of households (Chua, 2011).

A pilot programs spearheaded by mental health consultants have been developed to support the Native American teen mothers. Pregnant adolescents remain in school during their pregnancies and earn credits when they take courses in child and personality development associated with practicum experience in a specified preschool or day care center (Bailey, 2012). There, they learn to care for infants and young children hands-on and avoid the adverse effects of inadequate nurturance such as infants suffering from developmental problems. They also learn to relate to babies and children and gain experiences in caring for them. They learn how to stimulate them by holding, playing, entertaining, talking to them, and observing their behaviors in various settings. Even after these adolescents give birth, they continue with their education with their babies. Lessons available for them include dealing with motherhood, relationships, and relating to adults. Sometimes, their boyfriends, often their children’s fathers, attend sessions with them to bond and learn more about parenting (Golding & Hughes, 2012).

In recognition of the pathetic state of Native American women, President Bush in January 2006 mandated the Violence against Women Act with special provisions for such indigenous women. Under this act, Native American women are protected from assault by prosecution of anyone who commits such violence against them in the federal court. Serial sex offenders in tribal nations shall be tracked and entered in Indian Country sex offender registries. The act aims to prevent domestic abuse against women and create victim support with new grant programs. The Act also calls for funding for a baseline study of domestic abuse to get to the core of the problem and address it, so domestic abuse shows significant ,reduction if not eradication (Ritzer, 2011).

Being people of color, Native Americans are usually subject to racial discrimination. Their racial reputation precedes them, and they are being adjudged accordingly, and it follows they are treated based on such reputation (Banados, 2011). Some stereotypical labels given to Native Americans are drunken Indians, the Squaw, and the Indian princess (Schiffer, 2014). The drunk Native American stereotype stems from the time when Native communities traded with colonists, but due to their inexperience with alcohol, they easily got inebriated to the point that they couldn’t function normally. This stereotype portrayed Native Americans as naturally inferior, lacking self-respect, dignity, self-control, and morality (Schiffer, 2014). A drunken Native American Indian woman, on the other hand, is seen as dirty and negligent of her family in favor of alcohol. Another stereotype of a Native American woman is the squaw, which means she is primitive, ugly, and lacks grace. She is an unattractive and haggard, subservient and abused tribal female who is considered the tribe’s prostitute or a harlot, perceived to be of very low moral character (Bond, 2012). She is the opposite of the Native American Indian princess, another stereotype of Native American women, drawn from the character of Pocahontas, made popular by the Disney movie of the same title. This stereotype is portraying her as the noble savage, who collaborates with White men to subdue her people (Lajimodiere, 2013). Although it seems that the stereotype for the Indian princess is positive, it is a euphemism to demean the successes of Native American women. These stereotypes spring from a white colonist viewpoint rather than from the first-hand experiences of Native American women.

Native American Culture in Child Rearing

The comparison of value orientations of modern Anglo-American values and traditional Native American values differ much on their relationship with nature, tradition and group practices, family relations, thinking, and communication inclinations. Huston and Howard (2011) recount how very personal as well as communal raising a Native American child is within a tribal unit. When an Indigenous woman discovered she was carrying a child, she would actively engage in song and conversation with the unborn child. This bonding ensured that the infant knew it was welcome and planted early seeds of respect and love. This new life was viewed as being eager to learn, a willing seeker of traits that would guide understanding of the self and others (Joe & Gachupin, 2012).

Each child is traditionally believed to have what it takes to grow into a worthwhile person. The whole tribe expects a child to manifest good behavior, and this becomes the child’s motivation to be good and to feel connected to the tribe (Bailey, 2012). As suggested by the attachment and family systems theories, children’s warm reception by their family and establishment of positive relationships are crucial to their development. Their identification with the tribe takes precedence over their individuality (Golding & Hughes, 2012). Raising the child with indigenous practices is a cooperative communal effort including the child’s grandparents, great-aunts, and uncles, younger aunts and uncles, and even adopted relatives. Children have a very special place in the society, and they are considered gifts from the Creator. The parents and caregivers are tasked to nurture the children and implant in them seeds of honor and respect. Respect is reinforced by honoring them through ceremonies, giving them worthwhile and meaningful names, or recognizing them in special events such as in honorary dinners, dances, or giveaways (Gentry & Fugate, 2012). Giveaways entail giving children special items to honor them and their good deeds. Many times, a caregiver would remove personal items of clothing, jewelry, or other possessions to give to a child while commenting,

The way parents and relatives speak about the child, often within his hearing range, affects how they behave, so positive language is used to enhance their self-esteem. Seeds of desired traits a parent implants in the child should be nurtured well by repeatedly acknowledging such traits when they manifest. When the child grows into adulthood, the traits will stay on with him and guide him to live a peaceful life (Turansky & Miller, 2012). Appropriate behavior is encouraged when parents. Even very simple efforts of children to help out are honored by the people around them and partake in tending the good seed. It also serves as cues to behave accordingly (Gentry & Fugate, 2012).

Disciplining Native American children is practiced in direct and indirect forms. One form of discipline believed to teach children of the consequences of their actions is noninterference or letting things happen the way they are meant to happen (Reiter, 2011). This concept does not imply inaction in the face of potential grave harm but allows a person to have a choice. For example, if a child refuses to eat, then the logical consequence is for him to be hungry. The parent allows it because the child has made a choice that leads to him eventually learning something. Ritzer (2011) differentiates noninterference from ignoring. When a child continues to misbehave, he is ignored or removed from the environment that used to enforce desirable responses from him, so he feels deprived of such positive conditions. When he continues with his inappropriate behavior, he becomes an outcast by the community. Others consider a deliberate disobedience to the rules and expectations that were made clear from the beginning. His punishment matches the gravity of his misdemeanor. Often, chastisement becomes the duty of an uncle or elder instead of the parent for the parent-child bond to be kept intact and avoid straining their relationship (Joe & Gachupin, 2012). Children are not considered bad because of their misdemeanors. Parents and community members prefer to see it as a lack of understanding on the part of the child. Hence, he or she needs to be given guidance according to what is right. He is made to understand that his actions affect the people around him whether they are positive or negative. Hence, more desirable behaviors are encouraged. Discipline, in indigenous beliefs, is associated more with the instilling of self-control and following rules rather than the imposition of punishment when a child strays from the righteous path (Hearst, 2012).

The Reservation

Life on the reservation is typically hard and impoverished. Frank (2013) reports that Native Americans experience twelve times the U.S. national rate of malnutrition, nine times the rate of alcoholism, and seven times the rate of infant mortality; as of the early 1990s, the life expectancy of reservation-based men was just over forty-four years, with reservation-based women enjoying, on average, a life expectancy of just under forty-seven years. Such dire conditions are echoed in the literature, with Banados (2011) reporting that while the national poverty rate is about 10% for Caucasian families, poverty rate for Native American families on the reservation is about thrice that rate. Unemployment rates have reached 50% or higher (Banados, 2011). The economic deprivation brought about by poverty results in low educational attainment, substance use, incarceration, child abuse, teen pregnancy, school dropout (Mileviciute et al., 2013). However, to counter such adverse effects, Native American communities make use of their traditional cultural values and practices to offer their youth the resources they need to develop optimally despite their dire circumstances (Hearst, 2012).

Reservation schools usually integrate culture-centric practices in their curriculum as opposed to dominant culture, while schools outside the reservation are less likely to include strong cultural contexts in their lessons (Gentry & Fugate, 2012). One example is the mandate given by the Navajo Sovereignty in Education Act of 2005 to its Navajo tribe schools. This mandate expects schools to incorporate its native language, culture, history, government, and character in the curriculum (Badinter & Hunter, 2011). The schools believe that, in doing so, they contribute to the preservation of the Navajo language and endurance of culture for the benefit of the future generations of the Navajo people (Navajo Nation Department of Education). Thus, people from the tribe should be welcome to offer their support and contribution to the school to enhance children’s knowledge of their culture.

Life off the Reservation

Relocating from the reservation into urban areas has overwhelmed Native Americans, as this is the first exposure to life outside the reservation. For most of those who relocate, they were not prepared for the urban trappings of technology and progress. It was exciting to find out about these. However, some who preferred to stay on the reservation warned those who went out about the deterioration of their Native American culture if they become too impressed with non-Native lifestyle. Miller (2013) explained that instead of dismissing their traditional Indian values as a hindrance to their success in modern America, some native relocates appealed to tradition being their source of strength. Former Bureau of Indian Affairs field agent and military policeman, Benjamin Reifel encouraged his Native American constituents to be hopeful and advocated for a change of attitude in creating the necessary cultural adaptation in order to function within the economic and social systems of the mainstream society (Miller, 2013). Still, the difficulty in finding a job, urban congestion, language barriers, and geographic isolation are strongly felt despite their enthusiasm for their new environment and the encouragement to be brave. Many returned to the reservation, but several also achieved varying degrees of success in their relocated homes (Miller, 2013).

Native American Parenting

In analyzing parent-child relationships in Native American families, especially the mothers raising their children single-handedly, it is worthy to look into attachment theories. Hearst (2012) explains that an individual’s experiences and significant relationships in the earliest stages of life are responsible for their survival functions as they grow and develop throughout the lifespan. Frank (2013) identified four kinds of attachment styles, namely secure, avoidant, ambivalent/anxious, and disorganized. Those who have formed secure attachments have no difficulty establishing close relationships with others. They form healthy, happy, and trusting personal relationships without any fear of being too dependent on them or being abandoned. These positive relationships are due to having grownups nurturing the young ones, with early attachments having all three components of closeness, care, and commitment. In contrast, some people establish negative, avoidant behaviors towards the persons with whom they have relationships (Gentry & Fugate, 2012).

Their avoidant attachments, formed early in life, made them reluctant to open up emotionally because they feel uncomfortable getting close to other persons. For these individuals, their independence and self-sufficiency should be maintained because when they were younger, they had been exposed to cold, unattached caregivers who did not provide them with the love and security they craved. Hence, they learned to fend for themselves. People who have formed ambivalent attachments are inconsistent in relating to others as they had grown up in an environment where their caregiver had also been inconsistent in giving them love and affection and have developed insecurities due to this. The same goes for those who formed disorganized attachments. As young children, they were exposed to caregivers who were not organized and had passed this trait on to the children. They usually engage in unhealthy relationships and develop dysfunctional behaviors (Huston & Howard, 2011).

Reiter (2011) points out that distressed Native American mothers, mostly still adolescents, may lash out at their babies because they are not ready to handle the demands of an infant. They become irrational, angry and hurt their children to stop them from crying or simply abandon and neglect these children (Badinter & Hunter, 2011). In turn, the infants and children are left poorly cared for, and healthy attachments are not formed. It makes it difficult for them to trust anyone or develop the confidence they need to ensure their well-being. The resulting developmental delays cause such a child to be deficient both in curiosity and in the physical ability necessary to explore and become an avid learner. The anger, hostility, depression, and isolation that may develop instead tend to destine the youngster never to learn to trust others or make sustaining relationships (Badinter & Hunter, 2011). Other outcomes of poor or abusive parent-child relationships, coercive parenting, and caretaker rejection are suicidality, and inability of children to become good parents themselves as adults (Flake, 2015). On the other hand, strong parent-child relationships prevent adolescents’ delinquent behaviors and its related problems among the Native American families. Such impacts of parent-child relationship on a child’s future relational well-being support the systems theory of intergenerational transmission of relational patterns.

In terms of academic performance, Gentry and Fugate (2012) contend that when parents and families have involvement in their children’s schooling, children improve in their behavior, motivation, and academic achievement no matter what socioeconomic background they have (Joe & Gachupin, 2012). Successful parental involvement included:

- Parenting (assisting parents in creating supporting home environments that foster student success);

- Communicating (keeping open lines of communication between school and home);

- Volunteering (recruiting parents to become involved in school and classroom programs);

- Learning at home (informing parents of effective practices in helping students with homework and other curricular activities);

- Decision making (engaging parents as advocates for both student and school success); and

- Collaborating with the community (providing parents with access to community resources.

Tyers and Beach (2012) found from their focus group interviews that Native American parents identified two types of school involvement, namely, school-oriented participation and home-oriented involvement. The school-oriented involvement included parents being active in communication with teachers and other school personnel, actively attending school events, volunteering their time in school and advocating for their children. Home-oriented involvement, on the other hand, referred to helping their children with school work, showing interest in their children’s educational concerns, encouraging their children to do their best in their studies, and enjoining other members of the family and community members in the educational processes of their children. Some parents complained about certain barriers in their involvement such as not feeling welcome in their children’s school, their own negative experiences in their school history, observations of the school’s nonchalance about their involvement, gaps in cultural sensitivity, and barriers in language and communication. Other parents identified their own limitations in being more involved in their children’s school such as financial constraints, lack of child care for those left at home, lack of resources and facilities to do work for the school, and transportation problems in going to school (Frank, 2013). Joe and Gachupin (2012) emphasized the value of collaboration between the home, school, and the community, as it is bound to result in the best outcomes for children.

Parenting Interventions

Native American parenting has been mostly affected by historical trauma, and to prevent further effect on younger generation, some parenting interventions have been designed, taking into account the cultural and environmental context of Native American families living in more contemporary times. Schatz and Klein (2015), for example, developed psycho-educational interventions for parents to manage the damage associated with historical trauma. The intervention exposed them to traumatic memories and cognitive integration in light of the tribe’s culturally accepted parenting practices to make them aware of the impacts of historical trauma on their parenting skills. The intervention provides opportunities for the parents to reconnect with their tribal culture and values, strengthens their kinship to their extended networks and empowers them as parents to know what to avoid with their children that they know will create much damage (Gentry & Fugate, 2012).

Tyers and Beach (2012) created an evidence-based parenting program called The Incredible Years specifically designed to incorporate traditional Native American beliefs and values as well as discussion of historical trauma and current injustices experienced in contemporary society. Significant improvements in parenting and child behavior are manifested as compared to a control group, proving that parenting interventions that are developed against the backdrop of historical trauma and a healing framework are effective. Another parenting intervention is the Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) developed by Sheila Eyberg, Ph.D. She created this program for families with very young children who have disruptive behavior disorders. The program fused two prominent child therapy models at the time namely, traditional play therapy, which focused on the child’s behavior and free expression of emotions in a safe environment, and child behavior therapy, which focused on the parent with the role of change agent based on social learning theories (Huston & Howard, 2011). This model aims to foster strong bonds between parents and their children and to build up parenting skills on setting limits and providing structures in reversing negative behavioral patterns.

Joe and Gachupin (2012) belief of the need to go back to consulting the old wisdom in the raising of children as the center of the circle is consistent with the PCIT’s principles of honoring children and the structure of making of relatives, which are Native American values. Essential to the Native American tribes is the circle theory which includes old wisdom about relationships, care for the environment, affirmations, identity, and inclusion. These principles have been applied to past generations, but were interrupted when the social composition of the indigenous people was threatened and almost shattered (Huston & Howard, 2011). PCIT has been found to be compatible with the traditional Native American parenting practices. It incorporates approaches from social learning theory, family system theory, and play therapy techniques that are all acceptable theories that natives already practice. Both the Incredible Years and PCIT focus on behaviors and relationships, and acknowledge children’s developmental levels with minimal cultural bias (Joe & Gachupin, 2012). PCIT teaches parents to be keen observers of their children as well as become good role models for them. This technique parallels the teachings of Albert Bandura, who claimed that people acquire behaviors through observation and, subsequently, imitation of what they have observed. The same principle was practiced by the Native Americans who taught children to watch and listen because it is by doing so that they get to learn new concepts (Reiter, 2011).

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, combined with motivational interventions, is well-suited for families devastated by substance abuse, which many Native American families are. Parents who have substance abuse issues are usually guilty of child physical abuse and neglect, disrupting their family’s peace, harmony, and stability (Gentry & Fugate, 2012). Native American principle of honoring children is relevant to the foundations of PCIT, especially when it applies similar principles from the circle theory and old wisdom. The Parent Training Manual of PCIT was incorporated with traditional Native American cultural beliefs and concepts in parenting to create a program to enhance the intervention for Native American families (Huston & Howard, 2011). Turansky and Miller (2012) reported the responses of parents to a community-based, culturally grounded mental health intervention for Native American youths. The intervention, called Our Life, was run once a week for 6 months, and it promoted the mental health of young people and reduced violent tendencies by involving parents as well as youths aged 7-17 years. The youth participate in four kinds of activities:

- Recognizing and healing historical trauma;

- Reconnecting to traditional culture and language;

- Learning and sharing culturally appropriate parenting practices and social skills for youth; and

- Building relationships between parents and youths through equine-assisted and other experiential activities (Joe & Gachupin, 2012)

Most parents welcomed the idea of exposing their children to their traditional culture and expressed their desire to raise their children based on its values. Many admitted their lack of knowledge of some traditional parenting philosophy and practices, having embraced the modern culture and wanting reacquaince with their roots. Parents reported better parenting habits as learned from the program. Some claimed they had increased their warmth and encouragement for their children, so they developed better self-esteem (Huston & Howard, 2011). Their discipline techniques have also become more positive instead of negative and rules are being better explained as well as the consequences of their actions are discussed to teach them life lessons. Less effective parenting practices were also reported to have decreased significantly such as the constant use of punishment, not involving the children in decision making, or being overly permissive with them. They also shared that there is an increase of their knowledge of resources that support them in their parenting such as some government agencies, other parents who provide helpful information, and even articles read from the Internet that provide them with guidelines on better parenting (Huston & Howard, 2011).

Anger management is addressed in the intervention and parents reported an increased ability to manage their anger. Communication between parents and children has improved. After the intervention, the parents found themselves with increased contact with their children and more frequent shared dinners, family meetings, and bonding experiences occurred. Apart from the improvement of parent-child relationships, the parents observed overall positive outcomes for their children’s behavior and well-being. School performance improved, and there was a significant reduction in delinquent behavior. The intervention resulted in commendable outcomes and was responsible in bringing the families involved in the program closer together (Gentry & Fugate, 2012). The interventions discussed recommend for environments that cater for troubled Native American families especially those headed by women in single-parent households raising their children off the reservations.

The Crow Indians of Montana

This study shall focus on the tribe of Crow Indians from the Northern Plains of Montana, as the women to be interviewed are from that tribe. This section now focuses on the history and lifestyle of the Crow Tribe in Montana. The Crow Indians of Montana accepted the cessation of their land in 1868. Although they were a peaceful people when they were ousted from their land at that time, within fifty years, they had representatives lobbying in Congress to save their last remaining property (Bond, 2012). The Crows persisted to keep their culture, as exhibited by anthropologist Fred Voget, author of The Shoshoni-Crow Sun Dance and other cultural articles, including one on the description of the Crow people’s personality types (Gross, 2013). Like most Native American tribes, the Crows are family-oriented. Members can rely on traditional clans and kins for support and protection of the orphaned children, poor parents, or disabled elderly members. This kind of close-knit value system amazed George W. Frost, who, when he was the superintendent of the Crow Reservation in 1877, observed a prevalence of marital infidelity. Polygamy was common and socially accepted, with the men taking as many wives as they could support, as adultery was not considered a crime. However, statistics reflect that Crows valued marriage. It is reported that 20% of Crows had four, five or more wives and, for each marriage, it was a long-term union (Huston & Howard, 2011).

Summary

Native American families have gone through much pain in the history of their people. This chapter discussed the events that caused the deterioration of the once-solid family structures that embraced traditional values and communal child-rearing of tribal units. Apart from the forced separation of children from their parents to be sent off to boarding schools or adopted by White families, migration outside of reservations of families seeking better opportunities have further contributed to the decline of traditional Native American culture, values, and practices. These have once been woven into fabric of integrity of the Native American people. Marred by hopelessness, Native American families who have been denied opportunities outside the reservation have resorted to alcoholism, substance abuse, and other negative factors. These have greatly impacted the parenting capabilities of Native Americans, especially the mothers who raise their children on their own. Historical trauma has left deep scars that have been passed on from generation to generation. Children imbibe them through family systems, exposing them to the negative outcomes of the traumatic experiences of their ancestors. Without proper guidance, these children may adopt some practices that they see which may have negative impact on their lives. As shown in this review, a common case is the abuse of alcohol, drugs, and cigarette. When they see adults indulge themselves in drugs and alcohol, they tend to believe that such practices are normal.

The Strengths Perspective Theory gives much hope that Native American families can rise from the ashes of their devastating experiences to achieve their goals and become resourceful members of society, whether they live on the reservations or have relocated outside. Mothers can find strength in their heritage of old wisdom in strong parenting values passed down from their Native American elders if they only become open to it. The parenting interventions presented show evidence that such strengths can surface and serve them well. Due to the dearth of research on the perspectives of Native American women raising their children outside the reservation, this study will endeavor to conduct interviews to explore the psychological health and what the state of their relationship with their children is. Each person has a story to tell, and this study hopes to collect a wide variety of stories of such women. The theoretical framework that this study will build on shall guide the researcher in understanding various concepts related to child-rearing among the African American mothers. After listening to Native American women’s perspectives, information about their individual and common problems, parenting approaches, dilemmas, and hopes and dreams for their children and themselves are going to be unearthed. Such information shall be shared in this study as well as the possible action that can be done to address their issues and concerns.

References

Alden, K., Lowdermilk, L., Cashion, M., & Perry, S. (2014). Maternity and Women’s Health Care. London, England: Elsevier Health Sciences.

Badinter, E., & Hunter, A. (2011). The conflict: How modern motherhood undermines the status of women. New York, NY: Cengage.

Bailey, J. (2012). Parenting in England, 1760-1830: Emotion, identity, and generation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Banados, L. (2011). Parenting with a purpose: Biblical principles for raising adolescents. Mustang, Okla: Tate Pub & Enterprises.

Becker, A., & Shell, D. (2011). Attachment parenting: Developing connections and healing children. Lanham, Md: Jason Aronson.

Bond, B. (2012). A, b, Cs to z of godly parenting: How to nurture a spiritually healthy family. New York, NY: Xlibris.

Chua, A. (2011). Battle hymn of the tiger mother. London, England: Bloomsbury.

Druckerman, P. (2012). Bringing up bébé: One American mother discovers the wisdom of French parenting. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Edgerley, S. (2011). 5 keys parenting: Separating fact from fiction – the no-nonsense guide to what really work. New Delhi, India: McGraw Hill.

Feinstein, S. (2012). Parenting the teenage brain: Understanding a work in progress. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Flake, E. (2015). Mama tried: Dispatches from the seamy underbelly of modern parenting. London, England: Oxford.

Frank, L. (2013). An encyclopedia of American women at war: From the home front to the battlefields. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO.

Gentry, M. & Fugate, C. (2012) Gifted Native American students: Underperforming, under-identified, and overlooked. Psychology in the Schools, 49(7), 631-646.

Golding, S., & Hughes, A. (2012). Creating loving attachments: Parenting with PACE to nurture confidence and security in the troubled child. London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Gross, C. (2013). Parenting without borders: Surprising lessons parents around the world can teach us. Hoboken: NJ: Wiley & Sons.

Hearst, A. (2012). Children and the Politics of Cultural Belonging. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Huston, S., & Howard, R. (2011). Footpaths & bridges: Voices from Native American Women Playrights Archive. Ann Arbor, Mich: the University of Michigan press.

Joe, J., & Gachupin, F. (2012). Health and social issues of Native American women. New York, NY: Praeger.

Kail, R.., & Cavanaugh, C. (2013). Human development: A life-span view. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Lajimodiere, D. (2013) American Indian Females and Stereotypes: Warriors, Leaders, Healers, Feminists; Not Drudges, Princesses, Prostitutes. Multicultural Perspectives, 15(2), 104-109.

McMahon, T., Kenyon, B., & Carter, S. (2013). My culture, my family, my school, me: Identifying strengths and challenges in the lives and communities of American Indian Youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(4), 694-706.

Mileviciute, I., Trujillo, J., Gray, M., Scott, W. (2013). Native American & Alaska NativeMental Health Research. The Journal of the National Center, 20(3), 42-58.

Miller, D. (2013). Willing workers: Urban relocation and American Indian initiative, 1940’s-1960’s. Ethnohistory, 60(1), 51-76.

Navajo Nation Department of Education. (2011). Navajo Nation: Alternative Accountability Workbook. WindowRock, AZ: Author.

O’Gorman, A., & Oliver, P. (2012). Healing trauma through self-parenting: The codependency connection. Deerfield Beach, Fla: Health Communications.

Reiter, A. (2011). Parenting an athlete. Mustang, Okla: Tate Pub & Enterprises.

Ritzer, G. (2011). The Wiley-Blackwell companion to sociology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Russell, S., Crockett, L., & Chao, R. (2011). Asian American parenting and parent-adolescent relationships. New York, NY: Springer.

Sax, L. (2015). The collapse of parenting: How we hurt our kids when we treat them like grown-ups: the three things you must do to help your child or teen become a fulfilled adult. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Schatz, K., & Klein, S. (2015). Rad American women A-Z. Hoboken: NJ: City Lights Books.

Schiffer, M. (2014) Women of color and crime: a Critical Race Theory perspective to address disparate prosecution. Arizona Law Review, 56(4), 1203-1225.

Seshadri, S., & Rao, N. (2012). Parenting: The art and science of nurturing. Delhi, India: Byword Books.

Stange, M., Oyster, C., & Sloan, J. (2011). Encyclopedia of women in today’s world. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Reference.

Thomas, D., Goff, S., Trevathan, M., & Thomas, D. (2013). Intentional parenting: Autopilot is for planes. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Turansky, S., & Miller, J. (2012). Parenting is heart work. Colorado Springs, Colo: Cook Communications Ministries.

Tyers, T., & Beach, N. (2012). Gin & juice: A guide to parenting. London, England: Bloomsbury.

Wilcox, W., & Kline, K. (2013). Gender and parenthood: Biological and social scientific perspectives. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

Yoshida, K., and Busby, D. (2011). Intergenerational transmission effects on relationship satisfaction: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Family Issues, 32(5), 202-222.