Leaman, A., F. Stevenson, & Bordass, B. (2010). “Building Evaluation: Practice and Principles.” Building Research and Information 38 (5): 564-577. Web.

According to Leaman, Stevenson, & Bordass (2010), the core pillars of a sustainable building rating system should clearly define standards for energy use, greenhouse emission thresholds, waste disposal standards as well as the desired indoor environments. The authors note that these are pivotal to coming up with clear definitions of an effective building rating system.

AIA Sustainability Discussion Group, (2008). Quantifying Sustainability: A Study of Three Sustainable Building Rating Systems and the AIA Position Statement. Web.

The design and construction market is dynamic and rapidly evolving. A good rating system must therefore be able to easily adapt to these changes and create better construction standards.

Dixon, T., Colantonio, A. & Shiers, D.(2007). A Green Profession: RICS Members and the Sustainability Agenda. Web.

In the RICS report (Dixon, Colantonio, & Shiers, 2007) it is noted that despite acceptance that the knowledge of non-existence of identical buildings globally and nationally, many building rating systems, the Australian one included, have failed to clearly incorporate these variations. This is the case with many global rating tools.

Garnaut, R. (2011). Garnaut Climate Change Review. Canberra. Web.

Garnaut (2011) emphasizes that changes in climate call for better construction standards and this is only achievable if gaps in existing rating systems are identified and corresponding actions are taken.

Driedger, M. (2012). Choosing the right green building rating system: An Analysis of Six Rating Systems and How They Measure Energy. Perkins and Will Research Journal Research Journal, 1(1): 22-41. Web.

Driedger (2012) like many others who have explored the building rating systems, emphasizes the importance of taking into consideration multiple aspects in understanding the strengths and deficiencies of building rating systems. He notes that among other areas, the Australian building rating systems have successfully addressed the issue of CO2 emission reduction effectiveness, certification costs, and eases of adoption in the market but have failed to take into consideration diversity issues.

Smith, T.M., Fischlein, M., Suh, S. & Huelman, P. (2009). A COMPARISON OF THE LEED AND GREEN GLOBES SYSTEMS IN THE US. Web.

Buildings should be designed for long life and this is only achievable with efficient building rating systems. However, irrespective of how strong the buildings are, if they are not supportive of greener initiatives, then they cannot fit into the future. This is well ensured by the Australian green building systems.

Ellison, L. & Sayce, S. (2007). Assessing Sustainability in the Existing Commercial Property Stock: Establishing Sustainability Criteria Relevant for the Commercial Property Investment Sector. Property Management, 25(3): 287–304.

There is a widespread acceptance that an entire building design technique should uphold green designs which are sustainable and not just by the book. The design tools should set parameters that ensure improved quality and optimum designs, in addition to reducing life cycle environmental effects. Additionally, the system should enhance buildings’ life cycle costs. According to Ellison & Sayce (2007), the Australian system successfully achieves this.

IPF. (2007). The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive and Commercial Property: A Situation Review. Investment Property Forum (IPF). Web.

IPF (2007) notes that the use of a single sustainable building rating system provides a benchmark for comparison to existing building structures and the development of mechanisms for tracking processes in the design and operation of the best buildings. It notes that while the Australian building rating system acts as an excellent benchmarking tool, it fails to provide guidelines for process monitoring.

Ballinger, J. A. (2010). The Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme for Australia (BDP Environment Design Guide No. DES 22). Canberra: The Royal Australian Institute of Architects.

In Ballinger (2010) it is noted that evaluation of buildings on basis of rating systems is pegged on six fundamental principles, where an intelligent building is defined as one where all the six principles are addressed. He goes ahead to state that such a building offers production costs efficiency within its environment through minimization of the basic elements including building site, space planning, energy efficiency, greenhouse gas emissions, cost efficiency, and ease of construction. While praising Australian building rating systems in almost all these areas, it faults the way the systems address the issue of building sites.

Reed, R., Bilos, A., Wilkinson, S., & Schulte, K. (2009).International Comparison of Sustainable Rating Tools. JOSRE, 1 (1): 1-22. Web.

In noting the existing gap between rating systems, Reed, Bilos, Wilkinson, & Schulte (2009) stated, “While it is possible to directly compare the value of an office building in New York City, Berlin, London or Melbourne using a ten-year discounted cash flow approach (after allowing for exchange rate variations), making a similar direct comparison of the sustainable features and rating of the same building is quite complex. In the past, it appears there has been an unwillingness to compromise or admit a particular rating system may not be the possible best tool, which in turn has been a barrier to developing a global rating system (2).”

Myers, G., Reed, R. G. & Robinson, J. Sustainable Property: The future of the New Zealand Market. Pacific Rim Property Research Journal, 2008, 14:3, 298–321. Web.

Sustainable energy use is a primer in the rating of various building rating systems’ performance and ability to meet emerging marketing needs. While the Australian system may be said to have fallen short in other areas, in sustainable energy rating, it does an excellent job.

Fowler, K. M. & Rauch, E. M. (2006).Sustainable Building Rating Systems Summary. Web.

According to Fowler, K. M. & Rauch, E. M. (2006) most rating systems fail to fit the schema of sustainable building rating systems in terms of relevance, metrics, applicability in multiple scenarios, and availability.

Willrath, H. (1992). Energy Efficient Building Design: Resource Book. Brisbane: Brisbane Institute of TAFE.

According to Willrath (1992), the appropriateness and relevance of systems just like its gap in building rating systems can well be assessed by understanding five environmental aspects and an additional factor which is innovation and design. The five environmental factors are site sustainability, the efficiency of water use, energy and atmospheric considerations, materials and other resources, and lastly, the quality of the indoor environment.

Smith, T. M., Fischlein, M., Suh, S., Huelman, P., (2006).“Green Building Rating Systems: A Comparison of the LEED and Green Globes Systems in the US”, Report, Web.

According to Smith, Fischlein, Suh, Huelman (2006) a building rating system cannot be said to be effective or perfect if it imposes excess costs on the construction and hence raises the overall project costs marginally. Such a system despite offering green solutions and dealing with societal challenges is non-feasibility and not suitable for the application.

Australian Property Institute. (2007). Australia and New Zeeland: Valuation and Property Standards. Canberra: Australian Property Institute. Web.

There are a myriad number of green building certification guidelines both at local, national, and international levels. Gaps are inherent between them /and although they bear similarities, it is not easy to ascertain which is greener than the other. Such gaps can only be discussed in the context of the client’s objectives or their applicability to different scenarios.

Work plan and milestones

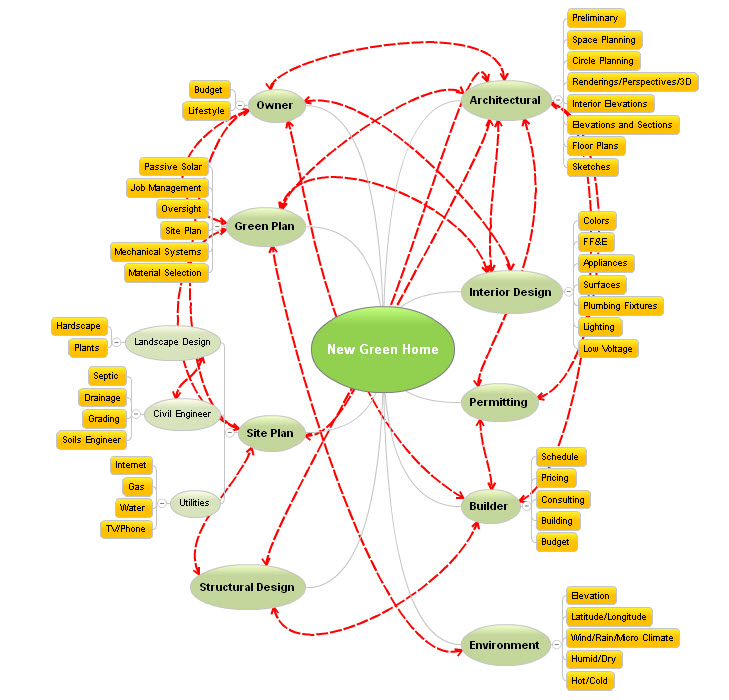

Mind map

References

AIA Sustainability Discussion Group, (2008). Quantifying Sustainability: A Study of Three Sustainable Building Rating Systems and the AIA Position Statement. Web.

Australian Property Institute. (2007). Australia and New Zeeland: Valuation and Property Standards. Canberra: Australian Property Institute. Web.

Ballinger, J. A. (2010). The Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme for Australia (BDP Environment Design Guide No.DES 22). Canberra: The Royal Australian Institute of Architects.

Dixon, T., Colantonio, A. & Shiers, D.(2007). A Green Profession: RICS Members and the Sustainability Agenda. Web.

Driedger, M. (2012).Choosing the right green building rating system: An Analysis of Six Rating Systems and How They Measure Energy. Perkins and Will Research Journal Research Journal, 1(1): 22-41. Web.

Ellison, L. & Sayce, S. (2007). Assessing Sustainability in the Existing Commercial Property Stock: Establishing Sustainability Criteria Relevant for the Commercial Property Investment Sector. Property Management, 25(3): 287–304.

Fowler, K. M. & Rauch, E. M. (2006).Sustainable Building Rating Systems Summary. Web.

Garnaut, R. (2011). Garnaut Climate Change Review. Canberra. Web.

IPF. (2007). The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive and Commercial Property: A Situation Review. Investment Property Forum (IPF). Web.

Leaman, A., F. Stevenson, & Bordass, B. (2010). “Building Evaluation: Practice and Principles.” Building Research and Information 38 (5): 564-577. Web.

Myers, G., Reed, R. G. & Robinson, J. Sustainable Property: The future of the New Zealand Market. Pacific Rim Property Research Journal, 2008, 14:3, 298–321. Web.

Reed, R., Bilos, A., Wilkinson, S., & Schulte, K. (2009).International Comparison of Sustainable Rating Tools. JOSRE, 1 (1): 1-22. Web.

Smith, T. M., Fischlein, M., Suh, S., Huelman, P., (2006).Green Building Rating Systems: A Comparison of the LEED and Green Globes Systems in the US. Web.

Smith, T.M., Fischlein, M., Suh, S. & Huelman, P. (2009). A COMPARISON OF THE LEED AND GREEN GLOBES SYSTEMS IN THE US. Web.

Willrath, H. (1992). Energy Efficient Building Design: Resource Book. Brisbane: Brisbane Institute of TAFE