Overview

A merger between Symantec and Veritas creates new challenges for both companies and demands a new effective approach to adapt to new structures and strategies effective for both of them. The existence of information resources could be measured by the degree to which companies have group support systems available for the use of knowledge workers. Since it has been shown that technology needs to be leveraged and embedded within the organization, it is more important to investigate the long-term impact of strategic communication technology decisions. Changes require a new structure and culture, new goals, and strategic approaches to business. Symantec uses individual and organizational measures to evaluate and analyze the effectiveness of the changes. To remain competitive, the new company has to pay attention and transform its performance management system and introduce effective technological solutions in this sphere. It should implement communication technologies that meet the needs of the company and potential users. There is a need to track the impact of communication technology over time and to match communication technology investments with measures of an organization.

Introduction

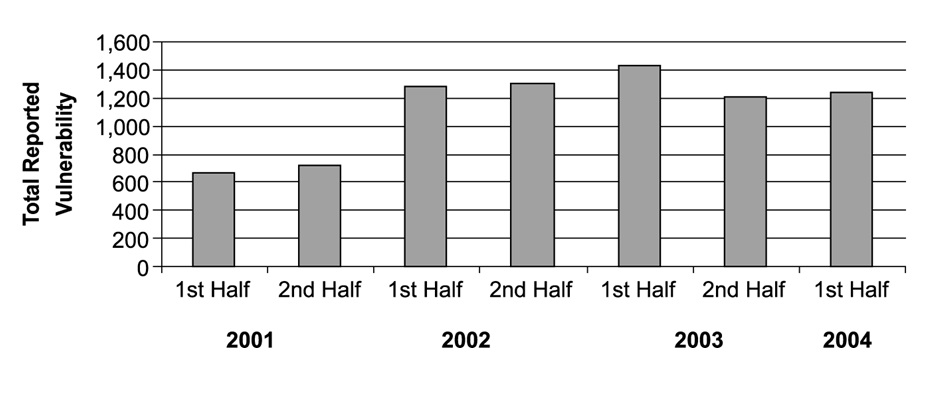

Symantec and Veritas are software corporations dealing with security and information management. The merger between these companies was closed in July 2005. The environment for high technology organizations like Symantec and Veritas is complex and presents a series of challenges to both companies. Symantec and Veritas are strongly impacted by the laws, cultural values, technology policies, and economic practices (Hahn and Layne-Farrar 2006). The technological environment is the most interesting and complex of all, and certainly is the one that most distinguishes the high technology arena from lower technology settings. Mergers between technology organizations are fueled by the technology, by the generation and communication of knowledge that can be used to solve a problem or accomplish a function. This merger creates new opportunities for entry and obsolete entire product lines, manufacturing, and design processes. the merger between Symantec and Veritas portrays that no one firm has sufficient resources to keep up with all directions and aspects–from basic research to product development in multiple technical areas.

Organizational Changes. Position before the Merger

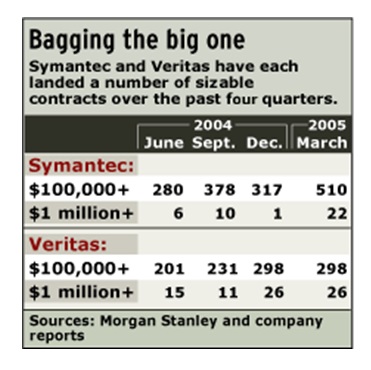

Before the merger, Symantec had 17,5000 employees and Veritas had 7000 employees. After the merger, both companies have to redesign their stricture and strategies to compete on a global scale (see appendix 1). The new company adopts the traditional structure of Symantec based on divisions and departments. Thus, a new structure gives autonomy to storage divisions of Veritas including the Veritas File system, Veritas Volume Replicator, and Veritas Volume Manager (Hamm 2008). “The idea was that by matching up the leading computer and network security company (Symantec) with the leading independent storage management company (Veritas), they’d be able to offer corporations a comprehensive set of solutions for safeguarding and managing their information” (Hamm 2008) (see appendix 2, 3).

New Demands

Thus, the majority of the old formulas used by Veritas did not work. After the merger, external as well as internal conditions impose the dynamic tension. Whenever process change is required, new efficiencies must be gained quickly despite uncertainties associated with applying the new manufacturing methods. An effective merger flows naturally from a sound strategic planning process. At Symantec, it is built from the ground up, with its foundation based on the firm’s underlying mission statement. Symantec management states: “While it is true that the size of our company will double and our customer base will be significantly larger, our ability to serve you will also double” (Symantec Home Page 2008). Symantec contemplating a strategy of growth does not change its corporate mission statement, thus it stipulates new goals and strategies for market management. “This strategic merger is not about cost-cutting; the new company plans to maintain the best of the employee base at both companies, particularly in the sales and support staff, to provide customers with a high level of attention and expertise. Additionally, the strength of our combined partners will continue to provide you with first-rate support” (Symantec Home Page 2008).

The strategy of Symantec is based on the idea that costs must be as low as possible to compete in software industries. “Veritas has 40 customer support sites throughout the world. Its main customer support operations in the United States are in Florida” (Software Makers Symantec 2005, p. A1). Similarly, if these companies are to efficiently develop new products, clearly an organic, amorphous structure will not allow them to create new product designs in the least wasteful manner possible. Efficiency is defined as performing or functioning in the least wasteful manner possible–an essential characteristic of contemporary electronic competition (Laudon & Laudon 2005).

These processes involve complex activities requiring a host of contributors whose participation must be effectively timed, coordinated, monitored, and redirected as the need arises. In short, these activities are organized and managed effectively. Ad hoc chance events do not do as an organizing philosophy (Local Technology Industry … 2005). Symantec supposes that explicit organization is the key to capturing the attention of thousands of employees who routinely create complicated end products (Mills, 2003). To cope with the torrid pace of technology development, four key aspects of structure in Symantec and Veritas are interacted to coordinate the many complex activities required in constant innovation: (1) a dynamic tension between (2) formal structures and reporting relationships, (3) quasi-formal structures, and (4) informal structures of the organization (Reed 2001).

Human Resources

In addition to having clear structures, Symantec and Veritas have changed also job responsibilities. Employees’ titles and jobs are clear; they easily stated their titles and readily described their responsibilities. These are also printed on their business cards and listed on the organization charts, which were shared with us, providing more evidence of clarity (Sims, 2002). Thus independent of title, there is high predictability of who has responsibility for what throughout these companies. This is an important finding regarding the contemporary, innovating organization. As both a product of prior successes and a requisite for future success, these companies are highly complex organizations.

Symantec and Veritas employees all produce thousands of products in multiple divisions, using state-of-the-art equipment and processes. The pace of technology development required to remain among the most successful innovators is murderous and will continue to be so. As a consequence, employees must have high predictability within their internal organizational environments. Clear structures and job responsibilities provide this predictability (Symantec to Buy Software Firm 2007). “The new Symantec is pioneering a technology frontier where the traditional definitions and separations of security and storage are disappearing. It’s time to seamlessly bridge the divide between security, device management, storage management, and systems and network management” (Symantec Home Page 2008).

Symantec and Veritas identify their cadre of highly trained and educated employees as their most important resource. These employees are expensive to attract, require ongoing maintenance of up-to-date skills and knowledge, and through experience develop local knowledge and networks of contacts useful to task accomplishment (Software Makers Symantec2005). Effective management of the performance of employees is a key to the success of the firm. It constitutes a competitive advantage as Symantec manages its people well is better using this important resource and will find it easier to attract and retain the level of talent required in a difficult technical and competitive environment (Sims, 2002). The nature of high technology poses special challenges that make performance management difficult.

Organizational Culture

Technology transforms the culture of Symantec and Veritas. A culture of hierarchy was perhaps inevitable in more stable contexts; the increasingly dynamic character of technology makes that culture obsolete. Changes in culture and the type of strategy take much longer to accomplish than changes in skills and procedures (Software Makers Symantec 2005). This analysis suggests that calls for a subtle change in the whole fabric of the organization, away from a conception of the organization as a production system and toward a new conception of the organization as a system with a dual objective of production and learning. As a result, not only do the higher levels of learning assume greater importance, but the content of policies at each level needs to change. The technological dynamism that characterizes competitive conditions calls for distinctively “dynamic” policies at each of the levels of learning (Robbins, 2004).

More dynamic learning policies in the skills domain add a focus on problem-identification and problem-solving know-why to the static policy’s focus on operational know-how; “training” becomes “development.” Strategy is primarily elaborated by general management; functional management’s role is primarily that of implementing this strategy, and the strategy is focused on attaining onetime step-function improvements in the market and financial outcomes. In the dynamic model, on the other hand, strategy is collaboratively elaborated by both functional and general management, and it defines both expected results and a capabilities growth path (Symantec Plant to Double in Size 2005). Symantec announces that “Through our unique portfolio of solutions, Symantec and VERITAS are best positioned to address the ever-growing needs of our customers. Based on IDC data, the total market opportunity for the combined company today is approximately $35 billion and is expected to grow to $56 billion by 2007” (Software Industry Leaders 2004).

Investments in Technology

Symantec understands that if investment into communication technology has not increased the value produced, management must rethink technology strategies. This has put managers responsible for determining the level of technology expenditure in a difficult position. While technology is viewed by Symantec intuitively as an important asset, managers do not know how to measure its impact, how to decide on the area in which to invest in it, or even how much to invest into it. Symantec management comments: “We intend for VERITAS storage products and Symantec security products to continue with their pre-merger release plans.

We do not expect any product “end-of-life” to occur as a result of the merger. As we continue the integration process, our focus on integrating our product and support/service portfolios will continue” (Symantec Home page 2008). Success is often regarded by Symantec as an absolute, something that either is or is not. Success and failure are relative matters, and can only be evaluated according to specific criteria and measures. Something that seems successful from one point of view often looks like a failure from another (Briggs, 2006). A particular set of results can be judged quite differently, depending on the goals and expectations of the person doing the judging. If, for example, one manager hopes that technology will be used by 80 percent of organizational members within six months, while the other simply wants the technology to be operational within the production facilities, the difference will certainly show up when the time arrives to judge the success of the technology (Cairns, 2003).

After the merger, Symantec/Veritas select promising business sectors for further growth. Emphasis is placed on selecting appropriate business sectors and ensuring that they are viable market segments for the firm to pursue. Historical trends, current expertise, and interest are all key elements in selecting an appropriate business sector. It is not enough to simply enter a new market because it is popular or has been in the news lately. Market studies must be made, the business sector defined, and the firm’s role within that sector established before any attempts are made to enter it. “For example, Symantec invested $332.3M or 12.9 percent of total revenue for the fiscal year 2005 in R&D, and VERITAS invested $342.7 M or 17 percent of revenue in 2004. Symantec will continue to leverage the strength and expertise from both VERITAS and Symantec” (Symantec Home page 2008). Once a broad set of acceptable sectors has been defined, it is then necessary to fine-tune this list into a small subset. Acquisitions must be aimed at improving the competitive position of the combined entity within the software industry.

Types of Technology Measures

To maximize effectiveness and minimize destruction, Symantec and Veritas use individual level and organizational level measures. Measures of communication technology outcomes were ordered sequentially as if moving along a chain – starting at the individual level and moving towards the organizational level. At each stage of the chain, technology success was evaluated from a different perspective. For this purpose, qualitative measures were mainly used, yet since the measures were at the beginning of the chain, it was difficult to distinguish between factors determining and those indicating performance (Hahn and Layne-Farrar 2006). A typical measure was user satisfaction. Moving along the chain, technology use becomes an important measure of success. the company management states that “the first six months after the close of the merger, product integration is focused on product compatibility testing, delivering product combinations to support solutions such as Business Continuity, Regulatory Compliance, and Email Solutions” (Symantec Home Page 2008).

Individual Level

This was an individual, behavioral measure. Symantec underlined that use should eventually translate into individual productivity gains, which, when accumulated, transform into organizational impacts, first behavioral and eventually organizational (Chase & Jacobs 2003). A measure that reflected the organizational impact of communication technology usage was decision accuracy. Moving further along the chain, communication technology investment areas were a basis for evaluations. Examples of measures used by Veritas and Symantec were the ability of the organization to develop intangible resources based on the employment of communication technology. The advantage of using technology investment areas lied in the ability to track each measure separately as various areas of the organization are scrutinized. The disadvantage lied in a lack of selection criteria, which indicated the areas that had to be taken into strategic consideration. At the individual level, user satisfaction was the most prominent measure for communication technology effectiveness.

The existence of instruments to measure user satisfaction had certainly encouraged the more widespread employment of this measure in evaluating communication technology effectiveness. According to the company’s strategy: “Within twelve months, Symantec intends to begin product-to-product integration, to rationalize and integrate licensing, and to integrate LiveUpdate™ into all products. The LiveUpdate™ component is an essential piece of technology providing a method to deliver product and security updates directly to the desktop, gateway or server” (Symantec Home Page 2008). Assuming that these measures were valid and reliable, they not only provide information about overall satisfaction with communication technology products and services, but the measurement of user satisfaction also allowed management to use the result as a standard for making comparisons across organizational units and over time within units. In addition, the measures were relatively simple and inexpensive to use within Symantec and Veritas. All these advantages encouraged the frequency of their employment (Lacy 2005).

Technology implementation research discovered that failure on the part of technology designers to pay attention to the reactions of users and the organizational context of implementation led to a lack of success. Since attitudes and beliefs measured in terms of user satisfaction were related to actual use, employing user satisfaction as an effectiveness measure was an important step in the direction of problem identification. The advantage of utilizing user satisfaction as a measure lied in the ability to diagnose possible causes of dissatisfaction with the communication technology and thereby suggest corrective action. User participation was cited as a measure for overcoming communication technology implementation failure (Lacy 2005). Symantec underlines that: “We believe that the foundation for any company seeking to achieve Information Integrity is a resilient infrastructure. By combining the right technologies, processes, and policies, companies can dramatically reduce the risk of unexpected disruptions and increase their ability to maintain continuity of normal business operations” (Symantec Home Page 2008). This was the case because user participation leads to user commitment, avoided resistance, and ensures that user requirements were met. At the same time, it was argued that participation in communication technology implementation was dysfunctional because of the inherent political problems that resulted from increased numbers of organizational members wishing to voice their opinions (Luftman et al 2003).

At Symantec, technology designers have the responsibility of implementing a communication system to serve the organization’s goals and to achieve customer satisfaction. To achieve the latter, Symantec technology identified the internal demands and needs of users and supply the technology that matched user requirements and the overall strategy of the firm. Identifying the needs of users – knowledge workers – was done in a variety of ways along with the formal-informal methods. At an informal level, communication technology designers asked workers to express their views about communication needs. A more formal system involved traditional surveys asking knowledge workers for their opinions. Focus groups were an approach that was somewhere between the two. Strategic approaches allowed the establishment of benchmarks for future comparison of technology needs, but qualitative forums provide richer information (Luftman et al 2003). “Symantec is moving toward a common platform for products and expects work to begin on that in 12 – 24 months. We recognize the need to incorporate integration efforts while minimizing any disruption to ongoing planned product enhancements and will design the implementation of the integrated platform to minimize the impact to customer operations” (Symantec Home Page 2008).

At Veritas, in addition to the identification of the knowledge workers’ needs, the implementation of technology went beyond a focus on the technical side. It was recognized that non-task and non-technical conditions were equally important in implementing technology into an organization’s social system. So the implementation of communication technology was viewed as a social and technological intervention. The social context was addressed when implementing communication technologies. To overcome this problem, communication technology designers gained a profound understanding of the user context, at both organizational and group levels to overcome potential barriers to implementation (Software Industry Leaders 2004). “Symantec will still provide a variety of consulting, education, support, managed security, and early warning services to customers, and remains committed to supporting customers with the right people, processes, and technology to enable information” (Symantec Home Page 2008). An organizing vision represented the product of the efforts of all the stakeholders to make sense of the innovation as an organizational opportunity. Since the implementation of new technology was associated with basic uncertainties concerning the requirements, design, and use of the new system, organizing visions helped in charting a successful course by facilitating the interpretation.

Organizing visions helped Symantec and Veritas in providing understanding about the usefulness and institutional necessities of the new communication technology (Symantec Begins Layoffs 2007). By linking the rationale to the business needs of the organization, organizing visions legitimize the innovation. This was supported by the reputation and authority of those who promulgate it. The organizing vision served the purpose of helping to activate and motivate the realization of the intended change by attracting necessary resources and facilitating exchange between organizational members (Robbins, 2004).

Organizational Level

Although organizational level measures were of central importance for Symantec and Veritas to be able to evaluate the company-wide impact of technology investments, the difficulty in operationalizing these measures led to the increased use of micro-level, or individual-level, measures. It was a cognitive measure that captures user attitudes and beliefs regarding communication technology (Hamm 2008). Behavioral measures such as real usage, which captured the extent to which organizational members employ technology were an equally good, if not better, a guide to increases in organizational productivity (which was the eventual goal of technology implementation). Productivity measures at the individual level were impact measures that reflected how technology enhances the performance of individuals. It was based on the assumption that improvements in the performance of several individuals would eventually translate into organizational performance improvements (Schuler, 1998). “Symantec intends to harmonize current offerings and evaluate opportunities for creating new service offerings. No new service offerings are currently planned for delivery at the close of the merger, however, new rules of engagement will enable us to provide the right services and experts to address the needs of our customers “ (Symantec Home Page 2008).

Organizational level measures focusing on the impact of communication technology were economic measures. For example, the communication technology expense ratio was related to return on assets. Measures capturing the response of the internal and external market to the introduction of communication technology were strategic measures. Obtaining a resource-based competitive advantage measured in terms of information-related research and development (R&D) expenditure was an example of this type of measure. Organizational measures that highlight the process refers to the extent that communication technology penetrated the organization in terms of the efficiency and accuracy associated with the distribution of information. An example of this type of measure was decision accuracy (Hamm 2008; Symantec Home Page 2008).

Another economic approach to evaluating the success of information technology was the cost-benefit approach. A cost-benefit analysis was a comparison between two states, whereby the proposed system is compared with the current system. For Symantec, it seemed logical to use the same organization before and after implementation as the comparison, there were too many mediating variables that affected the organization over time. Thus it was more desirable to look for an alternative system for comparison. Since information technology was frequently intertwined with business decisions, most senior executives preferred that a comparison be conducted against the level of service provided by a traditional system. Since it was compared to a zero-based budgeting process, it had the advantage of showing which objectives met at a lesser cost, given a manual alternative (Symantec to Buy Software Firm 2007).

At Symantec, the advantages of utilizing user satisfaction were profound, there were several theoretical and practical issues of concern. User satisfaction as a measure of communication technology effectiveness was associated with a view that knowledge workers were capable of pursuing two goals at the same time – achieving specified goals while also engaging in a variety of activities necessary to maintain themselves within a social unit. The view was that knowledge workers can attend to output and support goals simultaneously (Lacy 2005). When an organization conflicted with the need to attend to both output and support goals, support goals frequently dominated. Since communication technology fulfilled a support goal, it was not surprising to see cognitive measures being used frequently (Briggs, 2006). “Symantec offered a range of educational assessments, technical training courses, and end-user and partner certification courses designed to help users of Symantec’s security and availability technologies be more effective in deploying and operating those technologies” (Symantec Home Page 2008).

Evaluations based on attitudes were a response by users based on the belief that technology served a useful purpose. Thus, user attitudes were an underlying construct of user satisfaction. User attitudes were a slightly broader construct than user satisfaction, encompassing as they did the circumstances surrounding the behavior and conditions under which an attitude was formed. Measures of actual use were based on a view of the organization as a rational system whereby technologies were used to achieve goals (Briggs, 2006). ‘Symantec does not anticipate offering management and monitoring services for VERITAS technologies concurrent with the close of the merger. However, Symantec will evaluate the market opportunity and customer need for such services after the merger and may choose to offer these services at some future time “(Symantec Home Page 2008). From this view, the number and quality of outputs and the economies obtained in the transformation from input to output were criteria reflecting the role of communication technology in achieving organizational goals (Campbell, 1997).

The results showed three main factors as determinants of system use: decision support, work integration, and customer service. Decision support refers to the extent that technology is used to identify problems and improve decision-making. Work integration refers to the extent that technology helps in horizontal and vertical coordination of work, and customer service is concerned with using communication technology to provide support to internal and external stakeholders (Luftman et al 2003). This multidimensional construct has the advantage of investigating technology use along organizationally relevant dimensions, independent of the required or voluntary nature of use. In addition to assessing the perceptions and behavior of individuals using communication technology, the impact on their performance remains an area that lacks research. Productivity measures focus on the ability of individuals to increase their efficiency in performing tasks. Some of the measures that have been employed for this purpose are performance appraisals, the ability of technology in fulfilling managerial roles, and the perceived impact of technology by the user.

One study that assessed the relationship between technology and performance at the individual level investigated media choice and performance appraisal outcomes. They demonstrated that managers who match medium to message content are rated as being better performers (Mills, 2003). Technology was primarily used by managers to support and reinforce the informational role. This role was measured using such items as gathering market information, monitoring customer relationships, or informing other managers. Using communication technology, top management spent greater amounts of time reorientating middle managers. The study found support for the claim that communication technology usage depends on the organizational context in which it is deployed. Therefore, general predictions on increases in productivity across organizational contexts cannot be made. The requirements of high technology work and high technology employees both work against classical bureaucratic notions of control and require performance management practices that acknowledge uncertainty, rapid change, innovation, and professional standards and expertise. To some extent, the organizational requirements of the rapid-paced, highly interdependent technology and the professional standards and norms of professional and technical employees can work against each other. Managers tend to come from the technical ranks (Symantec Home Page 2008).

Recommendations

To improve the structure and manage organizational changes, Symantec should pay more attention to performance management and knowledge acquisition. High technology workers should be “knowledge workers.” Many are highly educated and trained in specialized fields of knowledge and belong to professional groups that have norms and standards and are defined not only by the content of their knowledge but by accepted practices and approaches to solving problems or conducting investigations. They arrive in the firm already “socialized” with a strong internalized set of expectations and values.

They have internalized standards, expect to be able to exert professional autonomy within the narrow bounds of their expertise, and experience collegial influence and control as more legitimate than hierarchical control. From the organization’s viewpoint, a performance management problem arises because of natural clashes between the orientations of professional scientists and engineers and the business needs of the firm (Laudon & Laudon 2005). The knowledge workers’ concern for creative freedom, the furtherance of the technology, and their position in a professional community can conflict with the business concern for targeted investment in strategic areas, planning, and control, and cost and budget. Interest in elegant solutions and autonomy clash with the business needs for a planned way to manage complex projects with many interrelated parts in a cost-effective manner that enhances competitiveness, and promptly brings the product to market before that of the competition.

The development of technological resources by using communication technology could also be a source of a sustainable competitive advantage. Internally developed communication-technology-based services, or the use of these internal services to create new technologies that can be sold externally, could be the basis of strategic advantage. In the strategic management literature, this has been measured using indicators such as expenditure on research and development or invested capital relative to sales (Laudon & Laudon 2005). To make these measures more specific to communication technology, one could measure communication technology investments as a percentage of total expenditure on research and development. These measures are based on the belief that firms with more advanced technological resources will develop more sophisticated products ahead of other industry participants.

Technology strategy locates the firm among elements in an inter-organizational network that advances the generation and application of technical knowledge. These are clusters of organizations that create both the critical mass and the diversity of elements necessary for technology advance to occur and for commercialization to result (Luftman et al 2003). The research university or research institute is the growth stimulus, providing the energy for technological innovations that can then be converted into products and processes. Financial elements such as venture capitalists or banks are available to underwrite the costs of this conversion. The symbiotic nature of the relationship between the research organizations, financial organizations, and the entrepreneurial organizations that exist to commercialize the ideas is significant (Laudon & Laudon 2005). Nevertheless, the need for both innovation and extensive interaction negatively affected the schedule and budget. Innovating and coping with interdependence by person-to-person interaction is critical to the quality of the work that is done, but is time-consuming and costly (Hahn and Layne-Farrar 2006).

Since the kind of performance required depends partly on the technology being used, performance management techniques have to fit with the technology of the organization. In this vein, high technology settings have certain characteristics that set constraints and requirements about how performance is managed (Ahmed et al 2001). Although there are many definitions of “high” technology, most of them deal with correlate aspects such as the high number of technical professionals, heavy use of research and development, and the rate of change in the product offerings of the industry, rather than with characteristics of the technology itself. If the essence of technology is knowledge, then high technology refers to knowledge with certain characteristics. Technology is at the high end of several interrelated dimensions of knowledge: it is complex rather than simple, new as opposed to established, at the boundaries of development and incomplete rather than complete, rapidly progressing not static or slowly developing, systemic not isolated, and contingent rather than linear (Luftman et al 2003).

The knowledge behind high technology is systemic. It cannot be isolated into neat packages and disciplines; previously separate knowledge bases, for example, join forces to form the knowledge base of new technologies (Turek 2004). This is happening in aerospace, where the new composite materials are revolutionizing aerospace engineering. Increasingly, high technology products and production processes are systems. They serve to link people and technological elements into mutually interdependent parts (Senior, 2001). The individual effects of a person’s behavior are lost as they interact with the behaviors of others and aggregate to contribute to the performance of the system as a whole. These systems are in turn embedded in other systems. Interdependent systems are exemplified and exacerbated by networks of information technologies that permeate our modern organizations. As a result, in high technology settings, people are highly interdependent with one another, and the contributions of individual efforts to the effectiveness of the system as a whole are not always known (Senior 2001).

Finally, high technology knowledge is contingent on which aspects of the technology have most recently been developed and which gaps in the developing knowledge domain people choose to fill next. The result is uncertainty. The development of technology content cannot be completely predicted, so the overriding need is to be able to respond to developments as they occur and to strategically choose points where subsequent development should be aimed. Much of the high technology of the software industry, for instance, is fueled by strategic developments and counter developments between the Eastern and Western blocks (Luftman et al 2003). These developments happen quickly, during the life of a development project, and can result in frequent changes in design. These design changes are not isolated but typically have ramifications for the design of the entire system. On the domestic front, the jockeying for position among computer manufacturers creates a similar dynamic. This uncertain, unpredictable nature of the direction of the high technology exacerbates the implications of the other dimensions (Senior 2001). This factor correlated most highly and consistently with all the other high technology factors and therefore appears to be a basic underlying component of high technology settings.

Conclusion

The merger between Symantec and Veritas portrays that software companies are faced with complexities and difficulties changing their structures and performance patterns. The example of the merger shows that technology managers must cope with the complexity of this environment. Two factors magnify this complexity. First is the rapid pace at which it changes. Rapid technological development results in an ever-changing combination of elements at local, national, and global levels. It does not depict the rapid technological development, the ongoing entry, and exit of competitors, or the mergers and acquisitions that move competencies and resources from one competitor to another. The global economy assumes an ever-changing form as newly developing countries emerge as fierce competitors, countries make forays and gain strongholds in new national markets, and governments pass protectionist or trade-enabling laws. This turbulence is the constant state of the high technology context. These forms are themselves presenting more strategic choices and more strategic uncertainty. They are not well understood and not easily managed.

Thus, one can understand a certain preoccupation with strategy. A successful firm must keep its eye on and find a path through many layers of ever-changing complexity. While keeping an eye on the environment, however, the organization must also tend to its internal functioning. The example of the merger portrays that the nature of the technology organization is a direct reflection of its environment and of the characteristics of the technology that it produces and uses. All aspects of the environment of technology firms are changing rapidly. Complexity is increasing because of the increasing number of players in the arena and the proliferation of national laws, trade policies, and cultures that are relevant to the global economy. In addition to technological resources, a firm may also achieve a strategic advantage by building information resources; these may take the form of intelligence embedded in the use of group support systems. Both the mere existence and the ability to exploit these systems provide the basis of an advantage. In today’s rapidly changing business environment, it is clear that there is a need for a reference point that can allow strategists to establish realistic benchmarks by which to judge the performance of a merger. Before the merger, Symantec and Veritas faced similar market conditions. Thus there is a strategic advantage for Symantec that can see the implications of the economic context for its industry and its markets. From this perspective, the use of technology by individuals in a work context fulfills organizationally relevant functions such as decision-making, the coordinating of work.

References

Ahmed, A.M., Chopoorian, J.A., Khalil, O.E.M., Witherell, R. 2001, Mind Your Business by Mining Your Data. SAM Advanced Management Journal, vol. 66 no. 2, p. 45.

Briggs, L.L. 2006, Calling for Backup: School Districts Are Searching for Ways to Manage Their Ever-Increasing Volumes of Content. New Technologies Are Here to Help. T H E Journal (Technological Horizons In Education), vol. 33, no. 10, p. 22.

Cairns, G. 2003, “Seeking a facilities management philosophy for the changing workplace”, Facilities, vol. 21, no. 5/6, pp. 95-105.

Campbell, D.J. 1997, Organizations and the Business Environment. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Chase R.B., Jacobs R.F. 2003, Operations Management for Competitive Advantage, Hill/Irwin; 10 edn.

Hahn, R. W., Layne-Farrar, A. 2006, The Law and Economics of Software Security. Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, vol. 30, no. 1, p. 983.

Hamm, S. Thoughts on the Symantec/Veritas Merger. BusinessWeek Online. 2008. Web.

Lacy, Suddenly Insecure About Symantec. BusinessWeek Online. 2005. Web.

Laudon, K. C. & Laudon, J. P. 2005, Management Information Systems: Managing the Digital Firm, 9th Edition.

Local Technology Industry Looking Forward to Growth. 2005, The Register-Guard (Eugene, OR), p. F5.

Luftman, J.N. Bullen, Ch. V., Liao, D., Nash, E., Neumann, C. 2003, Managing the Information Technology Resources: Leadership in the Information Age. Prentice Hall; US Ed edition.

Mills, H. 2003. Making Sense of Organizational Change. Routledge.

Reed A. 2001, Innovation in Human Resource Management. Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

Robbins, S. 2004, Organizational Behavior. Prentice Hall. 11 Ed.

Schuler, R. 1998, Managing Human Resources. Cincinnati, Ohio: South-Western College Publishing.

Senior, Barbara. 2001. Organizational Change, Capstone Publishing.

Sims, R.R. 2002, Managing Organizational Behavior. Quorum Books.

Robb, D. June 2001, Directory Enabled Networking: Coming Soon. Business Communications Review, no. 31, p. 52.

Software Industry Leaders Symantec and VERITAS Software To Merge. 2004. Web.

Software Makers Symantec, Veritas Plan to Join Forces. 2005, The Register-Guard (Eugene, OR), p. A1.

Symantec to Buy Software Firm. 2007, The Register-Guard (Eugene, OR), p. D1.

Symantec Begins Layoffs after Revenue Falls Short. 2007, The Register-Guard (Eugene, OR), p. B1.

Symantec Plant to Double in Size. 2005, The Register-Guard (Eugene, OR), p. a1.

Turek, M. October 2004, Messaging Compliance: Why It Matters; Are Your Company’s Email and IM Regulated by New Statutes? If They Are, What Should You Do about It? Business Communications Review, no. 34, p. 39.

Appendix

Semantec Growth Rates (before merger)

Symantec Veritas Performance

Symantec Curent stock Information