Introduction

Previously a thriving industrial district and one of the leading centres of lace production, the Nottingham Lace Market went on a sharp decline in the second half of the twentieth century. The physical core of the neighbourhood consisting of distinctive industrial buildings faced abandonment of demolition as it had no obvious further use. Today, the Nottingham Lace Market is revived, both thanks to the United Kingdom’s preservation programs and the public’s active participation in community building. This part of the city is now known both as a picturesque tourist attraction and a lively cultural, retail, and gastronomical.

It could be that the restoration of the Nottingham Lace Market is a prime example of finding a balance between preserving and restoring. On the one hand, the rich historical heritage needed a thoughtful approach that would maintain its authenticity. On the other hand, however, the Nottingham Lace Market was to become a place for social interactions and new beginnings. This ethnographic research paper inquires about the nature of tourists’, visitors’, and residents’ engagement with the neighbourhood and seeks to establish whether they are observers or active producers of the space.

Literature Review

When it comes to the urban development of historical quarters, both in terms of architecture and interior design, there is often a tug of war between preservation and revitalization. Facing an inevitable decline, the Nottingham Lace has long been in the centre of such a conflict (Crewe & Hall-Taylor 1991). Located in the very heart of Nottingham, the Lace Market used to be a world-renowned hub of the lace industry during the rise of the British Empire in the 19th century. By the mid-20th century, the lace industry declined to the point that the neighbourhood experienced high vacancy rates (Song and Oc, 2013). Some buildings had to be demolished for safety reasons; the Lace Market also lost parts to the city road widening project (Song & Oc 2013). All in all, the area was actively degenerating: it was considered unattractive and beyond restoration.

It was not until the 1960s that the Nottingham Civic Society came forward with a plan to “[encourage] good planning,” “achieve a worthwhile environment” and “preserve desirable aspects of the City’s heritage (Smith 1985).” As a result, in 1969, the Nottingham Lace Market was classified as a conservation area (Song and Oc, 2013). The decision was in line with a broader trend toward urban regeneration across the United Kingdom that was state-led,market-led, and interweaving the initiatives coming from the public and private sectors (Tallon 2013).

The 1974 Conservation Policy for the Lace Market sought to combine the preservation of the rich historic heritage and selective re-development. Back in the day, the United Kingdom’s government had high hopes for restoring the neighbourhood’s lost status as an industrial base (Smith 1985). However, soon it became clear that the textile industry would not return in all its previous glory, and the purpose of the buildings could not be preserved.

By the 1990s, the Nottingham Lace Market faced repurposing alongside further heritage conservation. Tiesdell (1995) explains that the neighbourhood faced the pressure to convert industrial buildings into office spaces. Yet, the rising rent and the City Council’s reservations regarding offices dominating the Lace Market resulted in a new turn of events. The neighbourhood saw the emergence of new ambitious projects, such as a new Lace Market Square, the Pod, and the Center for Contemporary Arts Nottingham (Song and Oc 2013). As a result, today, the Lace Market is one of the best UK examples of heritage-led redevelopments with a mixed-use of space. Song and Oc (2013) argue that there are positive physical outcomes. The Lace Market attracted new functions, integrated heritage into modern life, and provided quality public space. It is also now characterized by enhanced accessibility and vibrant but safe nightlife.

Though the processes of preservation and revitalization may seem juxtaposed, they serve the same purpose — that of urban regeneration. Roberts, Sykes, and Granger (2016) write that urban areas are complex and dynamic systems. Not a single city or neighbourhood is immune to internal and external forces invoking the need to adapt, be it growth or decline. Therefore, urban regeneration cannot be diminished to only one theme — reconstruction, renewal, conservation, and others. It is rather “a response to the opportunities and challenges which are presented by urban degeneration in a particular place at a specific moment in time (Roberts, Sykes & Granger 2016).” The development of the Nottingham Lace Market is an example of such a response. In the pursuit of preserving its identity, the government and other relevant institutions did not go as far as turning the area into a museum capturing and freezing a moment in time. Preservation was accompanied by new developments — bars, restaurants, and retail — and repurposing that breathed a new life into the Lace Market.

The logical question arises as to what the urban regeneration of historic areas seeks to ultimately accomplish. Boussa (2018) highlights the importance of a city identity because it strikes a balance between “constant” and “changing.” There is a need for finding “constant” and adapting them to the modern context. It is the invariants that lay a basis for social and cultural cohesion, facilitate communication between generations, and facilitate sustainable modern innovation (Boussa 2018).

As argued by Relph (1976), radical redevelopment would not satisfy people’s deep need for “for associations with significant places” and lead to what the researcher calls “placelessness.” Placelessness is known to lead to social unrest, which is why the 1970s UK public initiatives in the cultural field hinged upon the premise that art could improve morality and social order (Basset, 1993). It is safe to assume that had the Lace Market been demolished and deprived of its identity in the 20th century, the new developers would have had a blank, rootless space to work with.

The said placelessness can be an even more serious issue in a big city. In his now-classic essay The Metropolis and Mental Life, Simmel argues that the psychology of a city dweller was different from that of a villager (Leach 2005). City residents were less likely to build meaningful relationships established overtime because a city implied anonymity, change, and a high number of vendors (Leach 2005). Therefore, if urban development lets the cultural foundation decay and does not create spaces where people can interact, the environment can soon become lonely and conducive to social ills.

However, the relationship between the person and the environment is not one-sided. It would be wrong to assume that the city shapes its dwellers but remains immune to the internal force. In fact, there is constant mutual interaction between the community and the neighbourhood, both in the streets and inside the buildings. Interestingly enough, the new theoretical endeavours to understand urban neighbourhoods hypothesize that building physical objects is akin to building computer devices (Dalton et al. 2016). An object is a human artefact and a catalyst for the desired experience; it encourages behaviour or invokes reactions.

Moreover, residents can actively create value and produce space when interacting with the urban environment. Space production is a term coined by Lefebvre (2011) in his attempt to understand the ideology of space. According to Lefebvre, the said ideology bridges the gap between lived and perceived objects and places and “objective” scientific-technological spatial structures (Lehtovuori 2010). Lefebvre (2011) proposed a triadic division of space into

- perceived space that is a result of collective production of space through work and leisure;

- conceived space that is formed through signs and symbols at a higher plane;

- lived and endured space that requires the mediation of images and symbols.

It is important to note that space is about power and control; it is politically contested and provides opportunities for resistance through production.

Essay

Today, the Nottingham Lace Market is a lively hub that features iconic Victorian red-brick warehouses repurposed as museums, creative agencies, restaurants, fashion boutiques, and gastropubs. The neighbourhood’s demographic makeup also plays a role in how a community is developed. On the whole, Nottingham is one of the “youngest” cities as 50% of its population is under 25 years old (“About Nottingham” 2015). Besides, the Nottingham Lace Market in particular is one of the most ethnically and racially diverse places in the United Kingdom. While nationwide, around 86% of the population identify as white, for the Nottingham Lace Market, the percentage of the white population is only 57% (“About Nottingham” 2015).

Nottingham shows strong growth in the number of visitors, welcoming around 40 million domestic and international tourists each year. All these facts make it especially compelling to investigate how people use space. Perhaps, tourists are more observant while permanent dwellers are more creative as they reclaim their right to influence their surroundings. Besides, it makes sense to understand how the younger generation and those who do not originate from the UK interact with the historic heritage of the Lace Market.

Nottingham Contemporary

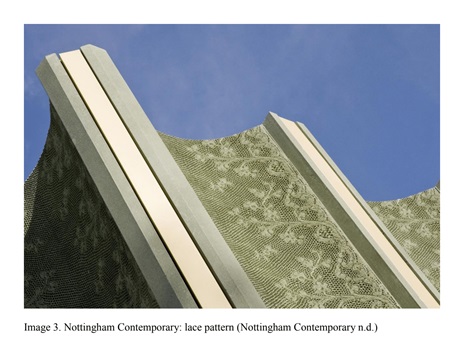

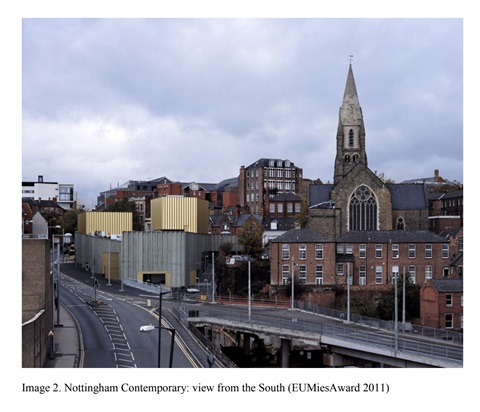

Opened in 2009 and formerly known as the Centre for Contemporary Art Nottingham (CCAN), Nottingham Contemporary is one of the biggest art galleries in the United Kingdom. Its site is said to be the oldest in the city as it is built upon the foundation of a Saxon fort (Moore 2010). From the first sight, the striking, blocky, homogenous geometry of Nottingham Contemporary seems to stand out among the intricate Victorian architecture of the neighbourhood. However, upon further investigation, I notice that the building pays homage to the Market’s historic legacy as it has a traditional lace pattern running across its verdigris scalloped panels.

The chief architect, Adam Caruso, said that he did not want “a pop, Warhol facade (Moore 2010).” Instead, he went for ambiguity and created the texture that is both soft and hard and an obvious but indirect reference to the lacy industry. I am impressed by this combination of constant and change, and the art centre stops seeming so outlandish among other buildings.

Even though Nottingham Contemporary appears to be completely different from its surroundings at first glance, a traditional lace pattern can be found on its panels, revealing much about the past of the neighbourhood.

Poised on a hill and surrounded by roads and living quarters, Nottingham Contemporary does not have an adjacent area where people could relax and spend time together. I am thinking of how a small square, a cozy park, or a backyard garden nearby could assuage the imposing and dominant impression that the gallery is giving off. I do not think I am the only one feeling this way. People are either entering Nottingham Contemporary upon approaching it right away or freeze in speechless admiration of its glory. They step back and take pictures, taking on the role of observers rather than equal participants. It is rather difficult to tell whether the gallery mostly attracts tourists or local residents. To better understand the audience, I decide to enter the building and continue my observations.

The view on Nottingham Contemporary from the South demonstrates that the art centre is surrounded by other buildings and roads, though its appearance is significantly distinct from the surroundings constructed in the same style.

The first thing, which visitors usually closely observe while visiting the art centre is its front entrance, which reveals the contemporary nature of the building and is rather minimalistic.

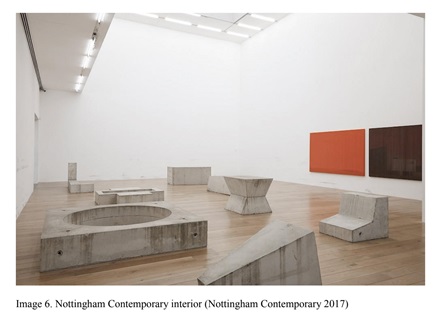

What I find inside is a classical gallery with top-lit white walls. Such kind of interior is versatile and universal; it can complement many art styles without drawing too much attention to itself. I discover both sole visitors and groups around me — friends, couples, and families with children. Visually, they belong to different races and ethnicities, and upon getting closer to them, I capture faint whispers in different languages – Arabic, French, Chinese, Russian, and others. People are dressed in a variety of ways, but mostly in casual and comfortable clothes, but the effort in putting together those outfits show that the visit to the museum is actually a special occasion.

It is interesting how people seem to obey the unspoken rule of talking quietly and respecting the space. Whenever children raise their voices, they are shushed by their parents. In Lefebvre’s terms, “conceived” space becomes “perceived” space and dictates its rules which later become a self-sustaining code of behaviour.

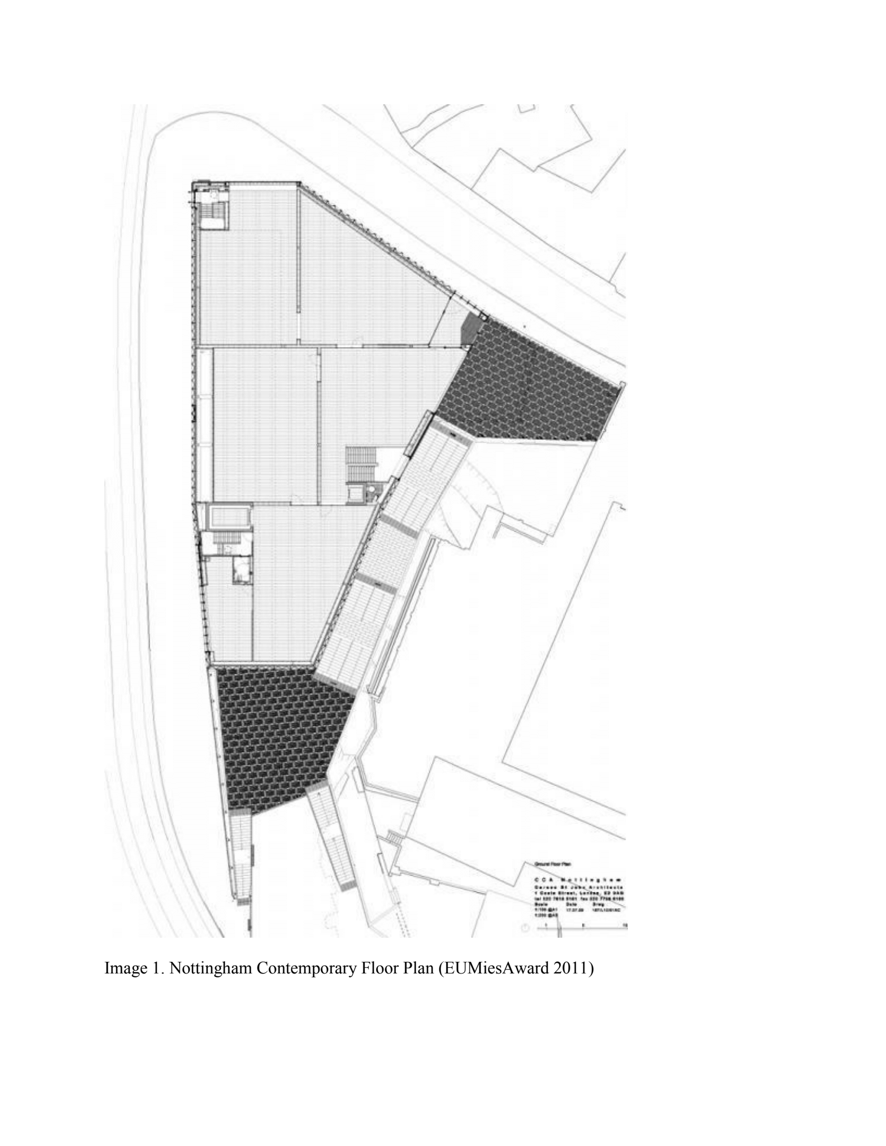

The floor plan of Nottingham Contemporary offers many valuable insights into how this large building is constructed, as it may be difficult to realize it while visiting the contemporary art centre due to its enormous size.

After walking around the gallery, I notice that its overall minimalist design has interesting features. In the lower floors, I discover double-height rooms with equipment for performances and installations hanging close to the ceiling. The walls have this raw, rustic feel, mostly due to the exposed concrete. Soon, I come to the realization that it is a running theme throughout the gallery that manifests itself in a lump of the plant on the roofscape and missing ceiling panels that reveal an intricate network of pipes and cables. This solution provokes more interaction from visitors: from time to time, I see people pointing at these interior details and making comments. I think to myself that maybe, these intentional imperfections break the pompous facade of Nottingham Contemporary, making it friendlier and more approachable.

The interior of Nottingham Contemporary with white walls seems to be universal, as it can easily complement a wide range of different styles without distracting visitors from what really matters – exhibitions.

The contemporary art centre is not only for observing works of art but also for interacting with other individuals coming from different backgrounds, learning from their experiences, and express one’s own ideas.

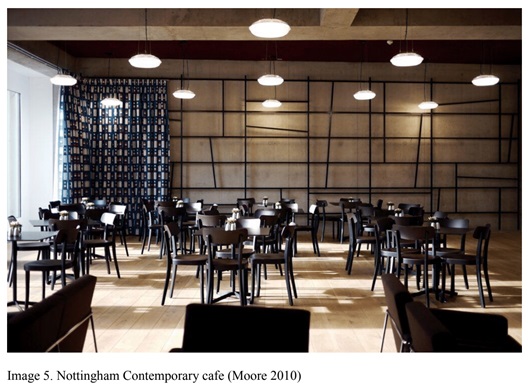

In search of a contrasting experience, I decide to take a look at the cafe with a little terrace and outdoor seats. Finally, I find a space that feels cosier and more secluded as opposed to the white halls that put every visitor on spot. The cafe has an airy, contemporary field and, despite the dominance of rigid geometrical lines, has a welcoming ambience. As expected, this part of the gallery is the busiest and the loudest. It seems as if in the gallery, visitors had to solemnly respect art objects and refrain from being too frivolous. The cafe, however, is a place for enjoying more earthly delights, such as eating delicious locally sourced food and having a friendly conversation. Nottingham Contemporary leaves me with an interesting impression of a place to quietly and a place to share thoughts and connect with others.

It is critical to note that the contemporary art centre also houses a cosy café-bar, which offers a contrasting atmosphere to that experienced within white halls where everyone speaks quietly.

The National Justice Museum

The National Justice Museum is a private museum located on High Pavement in the Lace Market area of Nottingham. This attraction is an example of repurposing a building with a rich, centuries-long history. From the 14th and until the 1990s, it had been used as a courtroom, gaol (jail) and police station and is, therefore, a historic site where an individual could be arrested, tried, sentenced and executed. In 1995, the building housed the Galleries Galleries of Justice Museum that was later rebranded the National Justice Museum (Mulhearn et al. 2017). Today, it includes two courtrooms, an execution site, and a jail in the basement. Like other heritage sites in the Lace Market, the National Justice Museum pays homage to its original purpose but reinterprets it to fit the contemporary context.

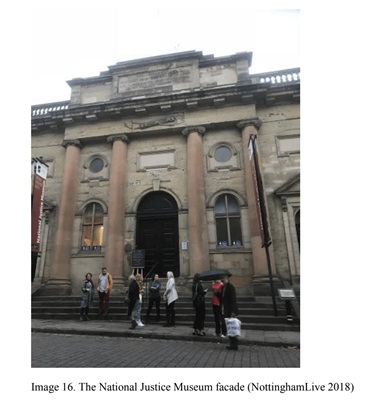

The National Justice Museum was rebuilt many times with the latest renovation dating to the mid-18th century. The building fits seamlessly with the rest of the street and has a pompous, solemn look. The architecture style can be characterized as classical, which is evidenced by its symmetry, proportions, and the front porch topped with a pediment. The evenly spaced out columns in the classical, Ionic order also speak in favour of the classical style. Despite its gruesome past, the museum looks welcoming and unsuspicious. It attracts passers-by in search of good background for a selfie or a group photo. Though unlikely in winter, it is easy to imagine people resting on the stairs leading to the front entrance, reading, or even having lunch. In other words, today’s tourists and residents no longer see this space for what it used to be and reinterpret its meaning.

The exterior of the museum looks pompously and demonstrates that the neighbourhood has a long and rich history worth exploration of people of different ages.

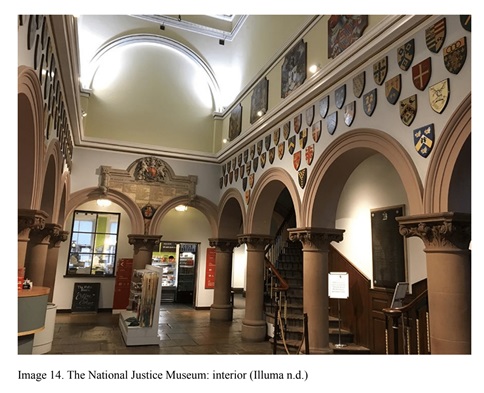

The interior of the National Justice Museum is rather diverse. Some of the rooms, such as the Victorian courtrooms, have been preserved down to the smallest details. Yet, they have not become untouchable objects of the past as they are still used in mock courtrooms as historically accurate decorations. Other galleries, however, have a more modern, minimalist design with bright, contrasting colours and geometric shapes. What stands out to me is how these galleries encourage visitors to take specific actions. For example, one photo gallery has sofas and chairs located conveniently next to the most fascinating items. As expected, I see people sitting there, looking at the pictures, and discussing quietly. Another interior solution is tables with small objects some of which can be held while others are kept under the glass. Similarly, visitors can comfortably take a seat and spend more time exploring.

It may appear surprising for many visitors of the National Justice Museum how Victorian courtrooms and modern galleries with bright and contrasting colours, as well as various shapes, can be housed in one building.

Probably, the main purpose of the National Justice Museum nowadays is to educate on the history of justice in the United Kingdom. I have always found the topics of crime rather serious and of little interest to children. To my surprise, a former courtroom and execution site appeared to be a family-friendly place with plenty of young visitors. From exploring posters and overhearing conversations, I learn that the museum offers courtroom workshops and hosts two exhibitions. One is taking a look at different types of punishments used throughout time, while the other discusses children and young offenders in prison throughout centuries.

What captures my attention is the lightheartedness with which people explore the museum. It is not uncommon to hear jokes and laughter as well as witty comments. It could be that the National Justice Museum’s strength is in igniting genuine curiosity in law and human rights through entertainment.

The National Justice Museum hosts different workshops and exhibitions, which encourage people to learn more about the history of justice in the United Kingdom, which is extremely exciting.

Church of St Mary the Virgin

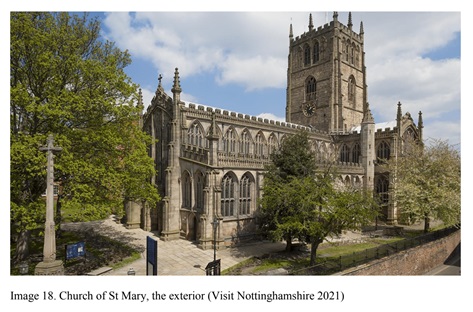

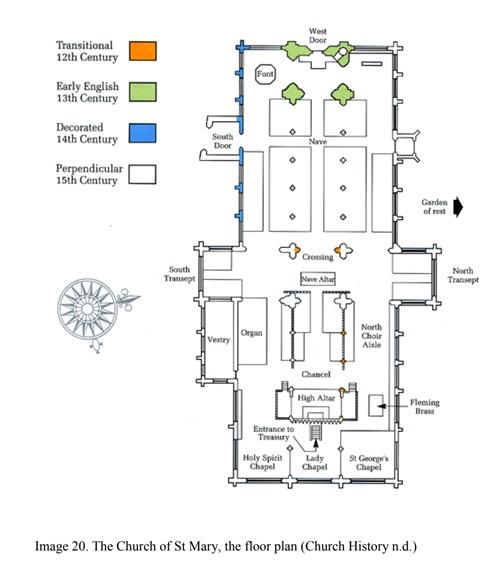

The Church of St Mary the Virgin, also known as St Mary in the Lace Market, is listed as a Grade I building by the Department for Culture, Media & Sport, which is an evidence of its great historic significance. The church is one of the only five Grade I sights in the whole city, the largest medieval building, and the second-largest religious foundation after Nottingham’s Roman Catholic Cathedral. The history of St Mary in the Lace Market goes back to Saxon times, but it is said that its main body was completed between the end of the reign of Edward III (1377) to that of Henry VII (1485–1509). Interestingly enough, the church has always served a variety of purposes. It hosted a Sunday school for children unable to attend regular schools, housed the town fire engine, and even ran workhouses. Today, St Mary remains a versatile space, keeping the old and assuming new roles in the contemporary context.

As a standalone building in the heart of the Lace Market, the Church of St Mary easily captures attention. I see people stopping in their tracks to look at the building. Whether they know its history or not, they freeze in admiration and take a moment to see all the interesting details. From the first look, it seems like the Church of St Mary the Virgin is attracting tourists more than locals. The tell-tale sign is the multiple pictures that they are taking and the poses they are striking — all very typical for social media. This time, I do not see many children for whom a visit to church may not be as entertaining as a walk in a park. The racial and ethnic makeup seems to be even; it is difficult to tell whether a particular group is dominating.

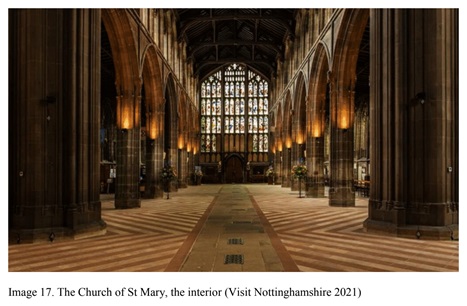

The interior of the Church of St Mary amazes, especially when visitors look up at the ceiling, which is designed in a gothic style, revealing the incredible grandiosity of the building.

The exterior of the church captures the attention of a multitude of passers-by, including locals, as well as tourists, taking pictures in front of the building, which is considered to be Grade I by the Department for Culture, Media & Sport.

Indoors is an even more enthralling experience mostly because of how overwhelming the perpendicular gothic style is. The first thing every visitor does is looking up in awe, realizing the grandiosity of the church. The place dictates its own rules, and regardless of their confession, any person keeps quiet and silently observes their surroundings. Whenever a child speaks up too loud, he or she is shushed and told to behave. It is quite curious how people tread with caution whenever they are at a place like the Church of St Mary. It looks as if there are invisible boundaries that one cannot cross unless they have a religious title. Therefore, it is not uncommon to see a visitor approach a particular space, such as a path to the altar, and suddenly stop, contemplating whether they have the right to do it.

The floor plan of the church of St Mary clearly demonstrates how it is structured and reveals its extremely engaging history, which has generated a special atmosphere, encouraging everyone to stick to unwritten rules such as staying silent.

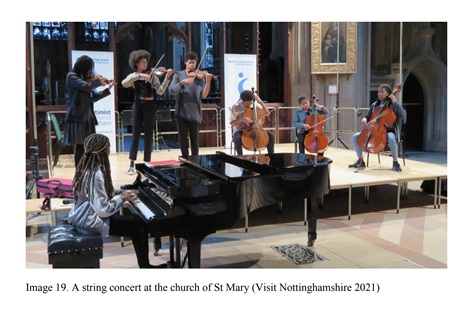

My observations make me think that churches may be one of the few historic sights that retain their “conceived” space. Even though the Church of St Mary is a tourist attraction as much as a religious foundation, its symbolic system still prescribes a certain behaviour. At other places, visitors were able to come up with activities of their own or, at least, interact with the environment in a preferred way. The Church of St Mary is different: there is only so much one can undertake there, regardless of their religious views. The church keeps on fulfilling its traditional functions: baptism, marriages, religious ceremonies, and services.

By the end of my visit, I notice that more and more people start to gather and take seats, waiting for something. From the conversations, I come to the understanding that there is going to be a string concert soon. The Church of St Mary seems to be an excellent choice as the event will appeal to both sight and hearing, creating a sensory-rich experience. While religion loses its popularity in the United Kingdom, it may no longer be the faith that will unite all church visitors. Music is a universal language that transcends cultures, races, ethnicities, and confessions. While staying true to tradition, the Church of St Mary finds its own voice amid the revitalization of the Lace Market.

Well-performed music touches people, and church architecture often amazes them as well; thus, the Church of St Mary the Virgin is a perfect place for various concerts, as visitors can experience a variety of sensory-rich feelings.

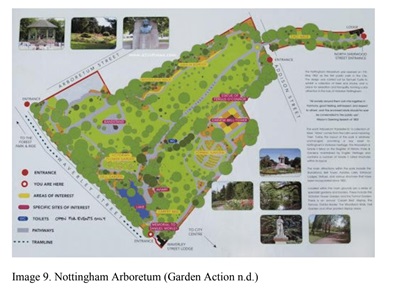

Arboretum

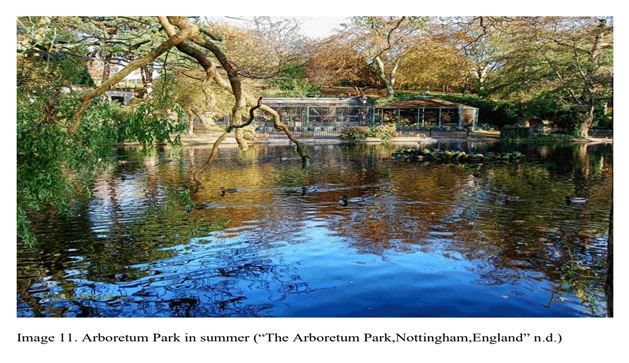

Now a residential area in the heart of Nottingham, near the Lace Market, Arboretum was the city’s first designated park under the Inclosure Act of 1845. Its design was the responsibility of the botanist and horticultural publisher, Samuel Curtis. The people behind opening the park to the general public were the Mayor of Nottingham, the lace manufacturer Felkin, and the Sheriff of the Borough of Nottingham Ball. It is quite interesting that the park was meant to be not just a place for leisure activities but a botanical collection preserved in the natural order. Today, Arboretum is the green lungs of the city that contains more than 800 trees belonging to 65 species (Elliott, Daniels & Watkins 2008). A park is a space that captures the authentic beauty of nature and adopts human developments without breaking its integrity. Like the Lace Market itself, Nottingham Arboretum is an example of finding a balance between preservation and revitalization.

Parks are considered to be more inclusive spaces than any others. According to Low et al.(2009), in parks, different groups of people are coming together in a relaxed atmosphere, and it is the parks that can break the boundaries of race, ethnicity, race, and gender. These assumptions seem to be true for Arboretum Nottingham as I notice more diversity than at any other place that I have visited so far. In fact, despite the cold weather, the park seems to be quite busy and filled with lone walkers, families, couples, and groups of friends. Compared to other sights on my list, the park seems to be the most family-friendly space. As a major attraction of the Victorian Nottingham, Arboretum attracts plenty of tourists, and as usual, I can hear foreign languages spoken all around. People from all walks of life come together to enjoy this winter day and contemplate the picturesque views that this place has to offer.

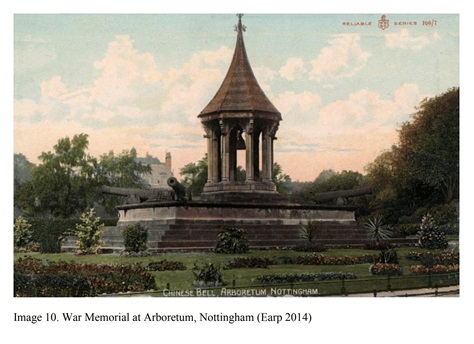

War Memorial at Nottingham Arboretum is one of the spots which captures people’s attention and encourages them to think about the past.

The meaning of parks seems to be rediscovered during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. As outdoor attractions, parks are safer than congested indoor spaces, such as pubs and cafes, that can become crowded and unsafe rather quickly. Perhaps it is the COVID-19 concerns which motivate people to rethink and put more value on outdoor leisure activities that can be done with proper social distancing and safety measures. This is the case for Arboretum Nottingham that remains popular despite the shutdown of its cafes and restaurants. I notice that all beloved gastronomical spots are closed, and yet, the park has not lost a bit of its attractivity. I see more joggers than ever than must be finding an emotional outlet in rigorous exercise. Likewise, children are more engaged with each other and not with their phone screens that must have become boring during the lockdown. All in all, Arboretum is an inclusive place that is subject to constraints due to the recent events but also a space that we reinterpret to fit our needs.

Nottingham Arboretum is a place which attracts people despite the weather as they visit it in summer, spring, and autumn, as well as winter, when it may be cold outside. The place reveals its beauty differently each season.

The park is large, as it includes not only multiple naturally beautiful spots but also various monuments, which can tell visitors more about the history of the neighbourhood.

Conclusion

The field trip to the Lace Market included some of its top sights, such as Nottingham Contemporary, the National Justice Museum, the Church of St Mary, the Virgin, and Arboretum Park. Each of the attractions has a rich history counting centuries and historic significance requiring careful preservation. The state in which all these sights are at the moment is in line with the goals of the heritage-led conservation in the Lace Market area. At the same time, they are not exempt from the ongoing revitalization process that rethinks public spaces and gives them a new purpose. The Church of St Mary, the Virgin and Nottingham Contemporary are probably the two spaces where the unspoken code of behaviour guides visitors the most.

In contrast, the National Justice Museum and Arboretum Park provide a space for collective co-creation. The park spiked in popularity during the pandemic, and now people are inventing new leisure activities to stay safe and sane at the same time. The National Justice Museum underwent a rebranding and went from spooky to educational and entertaining for guests of all ages. Previously a confined environment, it now welcomes people to take on the judiciary roles and travel back in time.

Bibliography

About Nottingham. 2015. Web.

Bassett, K. 1993. ‘Urban cultural strategies and urban regeneration: a case study and critique’. Environment and Planning A, vol. 25, no. 12, pp.1773-1788.

Boussaa, D. 2018. ‘Urban regeneration and the search for identity in historic cities’, Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 1, p.48.

Crewe, LJ & Hall-Taylor, M. 1991. ‘The restructuring of the Nottingham Lace Market: industrial relic or new model’. East Midland Geographer, vol. 14, pp. 14-30.

Dalton, NS, Schnädelbach, H, Wiberg, M & Varoudis, T. 2016. Architecture and interaction. Springer, Cham.

Elliott, P, Daniels, S & Watkins, C 2008, ‘The Nottingham Arboretum (1852): natural history, leisure and public culture in a Victorian regional centre’, Urban History, vol. 35, np. 1, pp. 48-71.

Leach, N 2005, Rethinking architecture: a reader in cultural theory, 1st edn, Routledge.

Lefebvre, H 2011, The production of space, tran. D Nicholson-Smith, Blackwell.

Lehtovuori, P 2010, Experience and conflict: the production of urban space, Gower Publishing, Ltd.

Low, S, Taplin, D & Scheld, S 2009, Rethinking urban parks: public space and cultural diversity, University of Texas Press.

Moore, R. 2010. Nottingham Contemporary by Caruso St John Architects. Web.

Mulhearn, R, Tennant, M & Forsdick C. 2017. Penal heritage: approaches to interpretation. Arts & Humanities Research Council.

Relph, E. 1976. Place and placelessness. Pion.

Roberts, P, Sykes, H & Granger, R (eds.) 2016, Urban regeneration. Sage.

Smith, R 1985, ‘Issues in urban industrial conservation: the Nottingham Lace Market’, Industrial Archaeology Review, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 139-153.

Song, S & Oc, T. 2013. The effectiveness of regeneration policy in historic urban quarters in England (1997-2010). PhD thesis, University of Nottingham, Web.

Tallon, A. 2013. Urban regeneration in the UK. Routledge.

Tiesdell, S. 1995. ‘Tensions between revitalization and conservation: Nottingham’s Lace Market’, Cities, vol. 12, 4, pp. 231-241.

Images

Church History, n.d., The Church of St Mary, the floor plan.

Earp, 2014, War Memorial at Arboretum, Nottingham.

EUMiesAward, 2011, Nottingham Contemporary Floor Plan.

EUMiesAward, 2011, Nottingham Contemporary: View from the South.

Garden Action, n.d., Nottingham Arboretum.

Illuma, n.d., The National Justice Museum: interior.

Moore, 2010, Nottingham Contemporary cafe.

National Criminal Justice Arts Alliance, 2020, Photo exhibition at the National Justice Museum.

Nottingham Contemporary, 2017, Nottingham Contemporary interior.

Nottingham Contemporary, n.d., Nottingham Contemporary front entrance.

Nottingham Contemporary, n.d., Nottingham Contemporary: Lace pattern.

NottinghamLive, 2018, The National Justice Museum façade.

Pittam, 2017, Nottingham Arboretum in winter.

The Arboretum Park,Nottingham,England, n.d, Arboretum Park in summer.

Traska, 2018, Nottingham Contemporary café.

Visit Nottinghamshire, 2018, A Victorian Courtroom at the National Justice Museum.

Visit Nottinghamshire, 2021, A string concert at the church of St Mary.

Visit Nottinghamshire, 2021, Church of St Mary, the exterior.

Visit Nottinghamshire, 2021, The Church of St Mary, the interior.