Introduction

As generations evolve from their traditional way of life to adopt modern ways of life, education is a critical part of the transition. Contemporary schooling systems have the task of creating structures and strategies for preparing students to easily adapt to life in the information era (Bingimlas, 2009). According to Koehler & Mishra (2009), teachers have a leading role in the creation of a favorable environment incorporating innovative opportunities for students to communicate, learn, develop and replicate what they have learned in real life (Koehler & Mishra, 2009).

A study by Firmin & Genesi (2013) revealed that most contemporary schools are adopting diverse teaching and learning programs supported by information technology (IT). Wong, Li, Choi & Lee (2008) emphasize the benefits from the introduction of technology at the primary level of schooling (Wong, Li, Choi & Lee, 2008). For example, introduction to technology at a young age helps build interest in learning how IT systems work early on.

About classroom needs, DiGregorio & Sobel-Lojeski (2010) explore how the use of interactive whiteboard technology (an example of information and communications technology, or ICT in lecture halls ensure that learning becomes more explorative, engaging, and enjoyable for learners at the primary level. Regardless of these discoveries, the adoption of ICT and other educational technologies has not been met with much enthusiasm in KSA. Tezci (2009) claims that ineffective adoption of technologies is caused by unprecedented barriers such as lack of better infrastructure and teacher attitudes towards the integration and implementation of technologies into the learning process.

A comprehensive understanding of the benefits of adopting technology and the barriers to its maximal integration and implementation in learning institutions will create a better platform from which to review the existing literature and explore the concerns associated with the implementation of ICT in primary schools in Hail City, Saudi Arabia.

Education in Saudi Arabia

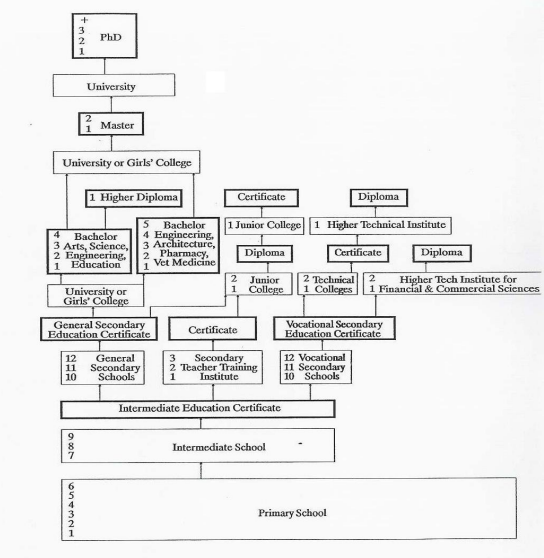

For the government of Saudi Arabia, education has remained a priority since the late 18th century. By 1989, Saudi Arabia had already created about 14,000 educational institutions, including seven universities, eleven teacher-training colleges, various technical training centers, vocational centers, adult literacy centers, and special needs learning institutions (Countrystudies, 2018). To ensure a smooth transition to the use of ICT at various education levels, the government has remained at the forefront in funding (Isman, Abanmy, Hussein, & Al Saadany, 2012).

For example, while looking at articles by Alarabiya New (2016) and Feteha (2017); it appears that health and education are the most-funded public services in the KSA. For instance, in the fiscal year 2017/2018, education needs were budgeted at 192 billion riyals, a slight drop from 228 billion riyals in the financial year 2015/2016 (Feteha, 2017).

Historically, primary school education formally began in Saudi Arabia in the early 1930s (Saudiarabiaeducation.info, 2018). In the year 1951, King Abdul Aziz set up the first publicly funded secondary school education system. In mid-1954, the Ministry of Education was established to operate the public institutions. The first university (King Saud University) was established in late 1957 (Saudiarabiaeducation.info, 2018).

Girls were not allowed to benefit from education until the year 1960. In 1975, the Ministry of Higher Education was developed to ensure that better learning systems were created within its purview. Nevertheless, it is critical to note that regardless of the difference between religious education and practical training, Islamic teaching has remained inseparable from public education. Religion creates the principles and moral background whereby policies and strategies are evaluated before implementation (Bakadam & Asiri, 2012).

Summary of the Education System in Saudi Arabia

Since the turn of the millennium, the Ministry of Education of Saudi Arabia has remained at the forefront of transforming the education system in the region. For instance, from the year 2000, the ministry has strived to create ICT-related educational reforms that require teachers to become IT, adopters, from the primary school to the higher-education level (Oyaid, 2009).

In realizing this goal, the Ministry of Education provided Learning Resource Center LRC administrators and teachers with training programs aimed at improving their understanding of IT infrastructure (Alenezi, 2017). The training programs are focused on training teachers on how to utilize IT tools and the current advances in technologies while supplying them with technical and theoretical knowledge on how they can implement ICT in their immediate school setting (Alghamdi & Higgins, 2015).

Despite the dedication and the determination of the Ministry of Education in boosting ICT adoption in learning environments, the movie has faced numerous barriers involving traditional offline methods of learning and teaching. Tondeur et al. (2008) find that the major barrier within the education system is a lack of technical know-how that could ensure that IT tools are maintained in working condition. Also, teachers’ attitudes towards this revolutionary transformation are sub-optimal. Teachers lack the initiatives to smoothen the adoption of ICT tools in the classroom (Tondeur, Keer, Braak & Valcke, 2008).

These issues are the foundation for exploring the barriers to this progressive and transformative move spearheaded by the Ministry of Education. Furthermore, reviewing these barriers offers a good opportunity to review the most effective integration strategies that could be adopted to establish the primary schools in Hail City, Saudi Arabia as technological leaders.

Information and Communication Technology

In the last few years, there have been increased reports and studies focusing on the opportunities and benefits associated with the adoption of ICT in the education system. Other than improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the learning and teaching processes, ICT has been found to improve the quality of education. According to Tezci (2009), ICT is a technology that makes up the infrastructure and components that effectively enable modern communication and computing integration.

Therefore, ICT is a central tool for building and nurturing knowledge in society. In the education sector, ICT ensures that school systems and processes are redesigned in a manner that efficiency in delivery is attained. As mentioned above, the Ministry of Education of Saudi Arabia has taken up ICT as a strategic resource in curriculum planning, teaching, and learning implementation. ICT involves computers, mobile devices, the internet, and interactive whiteboards to bridge the barriers present in classroom teaching and learning processes (Al-Ghaith, Sanzogni & Sandhu, 2010).

Passey (2010) found that ICT makes students more active learners compared to the conventional classroom environment, in which they are passive listeners and observers. Furthermore, Almalki & Williams (2012) highlight that ICT encourages collaborative learning, flexible learning opportunities, and effective problem-solving skills from learners. Benchmarking from global giants in ICT such as the US and the UK, Saudi Arabia has tried its best to enhance public education by adopting technologies that power the revision of the curriculum and introducing electronic tools into the teaching environment (Tondeur et al., 2008). In the year 2015, the ministry of Finance committed about £36 million in transforming the school curriculum while enhancing ICT amenities in learning environments (Albugami and Ahmed, 2015).

Nevertheless, the dedication by both the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Education has not been able to clear the gaps within the Saudi school system. While some researchers argue that the lack of an effective strategic approach by the government has resulted in the ineffective adoption of ICT in schools, others feel that teachers’ attitudes and societal-based barriers are the core issues hindering successful implementation (Bakadam & Asiri, 2012). Therefore, before reviewing these negative drivers, it is important to analyze what has already been done by both the government and the supporting agencies to implement ICT in the education system.

Notable success Indicators for ICT implementation

In the context of classroom affairs, ICT comprises a diverse set of technological resources and devices that effectively promote the interaction, creation, control, and distribution of data and information between teachers, learning resources, and students. These devices and resources include computers, laptops, desktops, projectors, the internet, and interactive whiteboards. In ensuring that Saudi Arabia realizes its ICT vision for education, the government has been in the lead in developing projects such as digital technology learning centers, learning resource centers, and computer labs in the country’s schools (Al-Ghaith, Sanzogni & Sandhu, 2010). However, Turel & Johnson (2012) reveal that successful implementation of ICT and associated technologies have remained a major challenge for both the government and the learning institutions (Turel & Johnson, 2012).

Technology Use in Education

According to Passey (2010), one of the core issues that result in ineffective adoption and implementation of ICT in education centers is the lack of factious justification for ICT incorporation in the classroom. Without this justification, educators or teachers are less concerned about how ICT works and how its integration would improve the flexibility and efficacy of their teaching processes (Passey, 2010). Therefore, Almalki & Williams (2012) emphasize that a lack of a solid understanding of ICT abilities within the education system results in barriers and challenges linked to adoption and implementation of those technologies, such as interactive whiteboards, in primary schools in Saudi Arabia (Almalki & Williams, 2012). So, how could the adoption of technology be streamlined in primary education?

Wong et al. (2008) determine that establishing a shared vision between the teachers, educational policymakers, and governmental agencies is the only way to facilitate adoption, appreciation, and execution of related educational technologies. Collaborative decision making and implementation are nurtured by the fact that they come with boosted productivity, supportive learning processes, and enhanced technological literacy (Wong, Li, Choi & Lee, 2008). As far as technological literacy is concerned, it is critical to review the diverse technologies already in use in the Saudi Arabian primary education system and the key performance indicators.

Types of Technologies in Use in Saudi Education System

Educational technologies have swiftly transformed teaching and learning environments in developed countries (Al Mulhim, 2014). Meanwhile, developing countries are actively striving to adopt and implement educational technologies in their institutions (Gray, 2010), including Saudi Arabia. To empower educational support, Saudi Arabia has adopted technologies such as interactive white, smart table technologies, computer interaction sessions, and the projection of course material software (Amoudi & Sulaymani, 2014).

The primary aim of adopting these technologies is to ensure that students are allowed to discuss, interact, and share information and new ideas with their teachers and peers. Through smart table technologies, students are given the chance to collaborate, interact, discuss, and enhance their learning processes through the use of digital augmentation (Albugami and Ahmed, 2015). The technology also offers them the opportunity to explore various digital lessons, search for relevant course solutions, and participate in educational games.

Most of the technologies adopted in Saudi’s educational system are multi-user in the sense that the design enables numerous students to participate in an interactive discussion at any given time. As a result, the students can enjoy the learning processes while exercising teamwork through a collaborative learning process (Gray, 2010). Moreover, the technologies are aimed at powering the connection between the teachers and the learners. With the implementation of technologies in the Saudi education system, it is essential to accurately analyze primary education and the technologies already in use (Amoudi & Sulaymani, 2014).

Primary Education and Technology

Primary schools are at the forefront of introducing young learners to the technological world. Technologies have been shown to make the learning process more enjoyable and effective for students at the primary school level (Schmid, 2010). As seen above, the introduction of Smart Tables in Saudi’s primary schools has made it possible for learners to enjoy a collaborative learning environment that boosts their learning capability (Gray, 2010).

Additionally, based on the fact that students have varying educational needs, at primary levels technology makes it possible for teachers to customize the learning materials and knowledge generation in such a manner that all the learners’ needs are met. Also, they are capable of making the learning process more creative and engaging for the students (Hockly, 2013). For example, they make it possible for teachers to involve both theoretical and virtual learning elements, making the learning process more encouraging and enjoyable for the learners (De Vita, Verschaffel & Elen, 2014).

Another common type of technology in the primary school system is the interactive whiteboard (IWB), which acts as an effective instructional tool in the primary school classroom. According to De Vita, Verschaffel & Elen (2014), teachers believe that the adoption of technologies such as IWBs makes the teaching and learning processes more effective and convenient for both learners and teachers. Most teachers argue that IWB technologies increase the efficacy of delivering course materials and increase interaction within the classroom.

As a result, the learning experience is stabilized and high knowledge distribution and adoption by the students are assured (Alsied & Pathan, 2015). Nevertheless, Türel & Johnson (2012) discovered that although IWBs present a wide array of features for teachers to utilize in the classroom, only a few of them are adequately utilized. They argued that the reluctance in exploiting these opportunities may be a result of limited knowledge, unseen barriers, and teacher attitudes toward IWB technologies (Türel & Johnson, 2012). Yang & Teng (2014) suggest that teachers should undergo training on the use of IWBs to remove barriers and optimize their use and in primary education (Yang & Teng, 2014).

A numerous and wide variety of existing empirical studies have examined the use of IBW in the classroom. For example, an article by Lai (2010) explores teachers’ perceptions of interactive whiteboard training workshops in Taiwan. The importance of an educator’s perception as a critical aspect of facilitating the educational process will be discussed later, but for this subsection, the empirical data that the article provides are of primary importance. Lai (2010) employed the method of a qualitative case study, retrieving meaningful and extensive results in this investigation of teachers’ perspectives towards the use of IWBs.

The primary results of this study indicated that training workshops are necessary to allow teachers to become familiar with IWB use, and the design of these workshops can reinforce the use of the interactive features that IWBs offer (Lai, 2010). Also, the experience of sharing appeared to be the most important benefit in the reported activities (Lai, 2010). Also, the results of these workshops could be reused in other circumstances as well as in arranging informal training to foster knowledge sharing after workshops (Lai, 2010).

Another notable study is the research by Beauchamp (2004), who investigated the use of IWBs in UK schools to develop an effective transition framework. By using qualitative approaches such as classroom observation and semi-structured interviews with teachers, Beauchamp (2004) established a generic progressive framework and developmental model for introducing IWBs in the context of the educational process. Beauchamp (2004) considered training to be a crucial aspect to introducing IWB technology, stating that school staff should be properly prepared before the implementation if IWBs as adequate preparation would eliminate most problems related to using IWBs.

It is also of critical importance to mention the research by Higgins, Beauchamp, and Miller (2007), presenting a review of the literature dedicated to theoretical and practical aspects of implementing IWB technology. The researchers argued that “training and ongoing support is required for teachers to use such technology appropriately and to support their selection of appropriate software” (Higgins et al., 2007, p. 218). Accordingly, it can be concluded that most academic authors recognize the importance of training and consider it to be a crucial aspect of an efficient educational process.

Other studies mentioned in this paper also investigated the factor of training as part of the efficient use of IWB technology. Arguably, an article by Isman et al. (2012) represents one of the most notable examples as it provides information specific to the Saudi educational environment. Also, an article by Türel and Johnson (2012) emphasizes an evident need among Saudi teachers for “training about effective instructional strategies using IWB” (p. 381). In general, training appears to be one of the most important aspects affecting teachers who intend to implement IWBs in their classrooms. Such authors as Alghamdi and Higgins (2015), Jang and Tsai (2012), as well as Albugami and Ahmed (2015), have pointed to a lack of training and experience as the most important factors negatively impacting the efficient implementation of IWBs in Saudi schools.

Interactive White Board (IWB)

According to Alsied & Pathan (2015), IWBs have become a common instructional tool in modern-day classroom environments. They provide high-tech technologies that can help analyze information to enhance teaching and learning processes (Alsied & Pathan, 2015). IWBs are defined by The British Educational Communications and Technology Agency as follow:

An interactive whiteboard is a large, touch-sensitive board which is connected to a digital projector and a computer. The projector displays the images from the computer screen on the board. The computer can then be controlled by touching the board, either directly or with a special pen. (BECTA, 2003, p 1)

Türel & Johnson (2012) emphasize that IWBs are made up of numerous built-in applications and features that are specifically designed to improve the quality of classroom interaction, and delivery processes in the classroom. For instance, it offers the teacher an opportunity to run video clips, animations, and presentations as a way of enhancing learners’ ability to understand the concepts. With these features, teachers can demonstrate issues, incorporate web-based resources, edit textual works, saves notes, display diagrams, and effective share notes with learners on-screen or through the student’s portal (Alghamdi, 2015).

Moreover, Farooq & Javid (2012) determine that IWBs facilitate a meaningful and engaging learning process making full use of the curriculum content. For example, in a science class, the teacher can smoothly showcase and explain abstract scientific concepts such as the solar system, the moon, and eclipses through the use of animations and real-life video. As a result, learners are allowed to imagine, understand, and describe a model based on what they are shown (Farooq & Javid, 2012). Similarly, in English Language learning, IWBs can be very significant in presenting linguistic fundamentals, English vocabulary, and phonics in a manner that enhances learners’ understanding (Isman, Abanmy, Hussein, & Al Saadany, 2012).

Furthermore, Thomas & Schmid (2010) observes that IWBs also have crucial presentation tools such as reveal, share, snapshot, and spotlight that provide the class with a chance to collaborate in the learning process. IWBs also offer the teacher the opportunity of recording all learning sessions and later sharing them with the learners for purposes of review and discussion (Thomas & Schmid, 2010). In case the teacher wants to remodel a diagram or wants to draw a chart, IWBs provides the space where the teacher can easily write, comment, draw, or annotate. All work done on the board can then be saved as an electronic file and later utilized for a repeated class session with other students (Celik, 2012). The board software is designed with the ability to link up with the school’s library. This means that teachers can easily search the library and showcase images, videos, or journals for course reading purposes.

This review has proved that IWBs increase and maintain a high level of interaction in the classroom by making it possible for both teachers and students to engage in the learning process. Therefore, it is critical to explore the specific benefits of using IWBs in the classroom (Isman, Abanmy, Hussein, & Al Saadany, 2012).

Significance of Using IWBs in Teaching and Learning

Enhanced Learning

In the tech-driven world, educators’ ability to capture learners’ hearts and minds remains a major challenge. Alghamdi (2015) suggests that the teaching and learning process is both a science and an art. Therefore, through the adoption of technologies such as IWBs, exceptional classroom results are assured (Alghamdi, 2015). In the context of IWB functionality, Kershner, Mercer, Warwick & Kleine (2010) revealed that it results in enhanced lessons. IWBs integrate different learning styles into a single experience. This means that learners are offered the opportunity to learn by interacting, hearing, and seeing. In so doing, it provides teachers with the chance of teaching the same subject material innovatively, improving the quality of the content (Kershner, Mercer, Warwick & Kleine, 2010).

Interactive Learning

Alghamdi (2015) finds that IWBs allow children to effectively interact with peers as well as with the learning materials. IWBs ensure that each learner becomes part of the lesson and can teach fellow students based on their level of understanding. According to Alghamdi (2015), while using interactive whiteboards, student understanding is based on their interactive drawing, writing, and touching the board. As a result, learning is made more interactive and collaborative.

Nevertheless, some teachers feel that these interactive classroom affairs would result in information overload for the learners hence ruining the learning process. Additionally, since the board encourages the use of educational games, teachers have the opportunity to measure learners’ decision-making ability as well as their learning progress. Also, data is easily customised or modified using specialized pens, making writing, drawing, and highlighting content more effective. As a result, efficiency in the output of the course material is assured (Celik, 2012).

Flexibility in the Classroom

As seen above, with IWBs, teachers can display different types of media on-screen with ease. For example, they can smoothly showcase photos, graphs, illustrations, videos, and animations with a diversity and abundance of options. Through these options, it becomes exceedingly easy to create innovative and customized lessons that inspire students based on their needs and abilities (Celik, 2012). As the IWB instructor tools are connected to the internet, the teacher is allowed to enjoy resources from both online and offline sources (Hockly, 2013). For example, teachers can enhance the teaching processes by searching for online videos on YouTube and Teachertube to provide learners with rich resources for learning and research.

Integrated Technology

IWBs allow the easy integration of various technologies that enhance the teaching and learning processes. For example, any device, such as a video camera microscope, computer, or gaming tool can be attached to the board, making the learning process more effective. With all these features and benefits, IWBs’ effectiveness in enhancing the teaching process is assured, as long as educators have a comprehensive understanding of the possibilities IWBs offer in the primary education setting (Celik, 2012).

Use of IWBs in the Primary Education Setting

Growth in the use of IWBs in primary education is part of the initiative of the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Finance of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to develop the transformative exploitation of ICT in education (Ministry of Finance, 2018). Alghamdi (2015) finds that IWBs present divergent opportunities and challenges to instructors and teachers.

For example, teachers without ICT skills tend to adopt a negative attitude towards IWB use in the classroom as they consider it hard to apply (Alghamdi, 2015). Additionally, teachers without formal training on IWB usage tend to find it hard to benefit from IWB features collaboratively and innovatively in a classroom environment (Al Mulhim, 2014). These challenges constitute the core reasons why most schools in Saudi Arabia are yet to enjoy a smooth transition to the use of technologies such as IWBs in their classroom environments (Shen & Chuang, 2010).

Teachers Perspective towards IWB

Teachers have varying perspectives when it comes to using IWB. Teachers exposed to initial training on ICT programs and the use of instructor tools view the IWB as an effective innovation that promotes pupil integration into the learning process (Shen & Chuang, 2010). Others feel that its flexibility makes it possible for teachers to demonstrate diverse information that makes the learning processes more enjoyable and innovative; the quality of ideas and information gained by the students is valuable (Hockly, 2013).

A good number of teachers view the IWB as a catalyst tool for transforming traditional instruction into innovative, constructive, and interactive teaching methods (Al Mulhim, 2014). The opportunities created by IWB make teaching enjoyable and productive compared with the traditional approaches. Nevertheless, there are those teachers who view IWB as an ineffective tool (Celik, 2012).

According to Farooq & Javid (2012), those of teachers who do not have any idea of how ICT tools work view IWBs as ineffective in the classroom environment. Others are concerned about the initial cost of setting up an IWB for classroom use (Al Mulhim, 2014). Furthermore, technical problems associated with the functionality and maintenance of IWBs make it difficult for many teachers to appreciate it as an excellent instructional tool. Due to the integrative nature of IWB, some teachers argue that it may result in overload for learners, causing confusion and hindering the quality of education (Farooq & Javid, 2012). Nevertheless, De Vita, et al. (2014) reveal that all negative perceptions and attitudes towards IWB originate from uncertainty and unawareness of how the tool works and the benefits it can have (De Vita, Verschaffel & Elen, 2014).

The employment of a theoretical framework to indicate the perceptions of teachers is of high significance. In an article published in 1991, Ajzen justified the importance of such a framework by stating that it directly affects the teachers’ motivation to act in a certain way, along with their intention to use or not to use certain technologies (such as IWBs) in the educational process. Ajzen (1991) developed a theoretical model, the theory of planned behavior, that “traces attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control to an underlying foundation of beliefs about the behavior” (p. 206). The distinction between behavioral, normative, and control beliefs is the most important aspect of the model’s implementation. Also, it is appropriate to mention a study by Beijaard, Verloop, and Vermunt (2000), in which the researchers considered teachers’ perceptions of professional identity to be a crucial aspect in an efficient educational process.

Barriers to using IWB in teaching and learning

Human Barriers

According to Farooq & Javid (2012), a lack of sufficient training and know-how on the use and exploitation of different features of IWBs remains a primary barrier to the effective adoption of the technology by teachers. Teachers without knowledge of IWBs find it difficult to manage their students and course materials using the technology (Al Mulhim, 2014). Similarly, a lack of appropriate and specific curriculum content directed towards the IWB creates a huge information gap that affects the smooth transition and adoption of the technology by teachers. Also, a reluctance to make time for using the IWB constitutes a significant barrier to its use and appreciation by instructors (Farooq & Javid, 2012).

Physical Factors

Physical factors are also related to the ability to employ ICT resources within an educational environment. For example, issues related to the accessibility of ICT requirements -there are requirements that computer labs should be well designed which make it difficult for some public schools in the rural regions to adopt technological advancements, technical support, internet support, and understanding of computer equipment influence the likelihood of IWB adoption (Al Mulhim, 2014). Due to the cost involved in purchasing IWBs, financial barriers can also prevent teachers from getting the opportunity to acquire them.

For example, in most government-funded schools, the lack of budget for buying whiteboards for schools and the supplementary budget for training presents a challenge (Shen & Chuang, 2010). Thinking critically, the barriers to using IWBs and the subsequent negative attitudes toward IWBs all originate from lack of training and support for teachers on how to utilize the technology. Barriers are experienced because teachers do not know how to integrate the technology into their regular teaching approaches (Al Mulhim, 2014).

Therefore, Alsied & Pathan (2015) argue that all barriers and negative attitudes of teachers towards IWB would be neutralized by initiating a well-planned training program, integrating classroom practice, and including IWB into the curriculum (Alsied & Pathan, 2015).

Cultural Factors

Cultural barriers touch on the general attitude of the school, the teachers, and the community as far as ICT adoption is concerned. According to Alghamdi (2015), school culture plays a critical role in determining whether technologies will be adopted or not. For example, some institutional barriers include the school leadership’s attitude towards technology, the managerial routine, and the general school curriculum. Others include the school time-tabling policies, staff training, and school internet connection (Alghamdi, 2015).

Gender differences in the use of IWB

It is also crucial to discuss the problem of gender differences in the use of IWB technology. As mentioned by Huang, Liang, and Chiu (2013), gender might present an important factor that influences the problem of “falling behind,” which “often exists when using computer-assisted learning with children” (p. 97). In the context of introducing IWB technology in Saudi schools, the question of the impact of gender differences on the educational process is of great importance. In the literature review section of their study, Huang et al. (2013) mentioned that in their observation of classroom interaction with IWB, “males dominate classroom interaction regarding the frequency of certain discourse moves” (p. 98). Huang et al. (2013) concluded that gender differences are substantial as girls tend to be more capable of retrieving and memorizing important information.

A research study by Öz (2014) also bears mentioning as the author paid significant attention to the factor of gender in the process of implementation and use of IWB technology. The investigation was largely based on the interpretation of extensive quantitative data. The author’s conclusions included the observation of a lack of gender differences related to the perception of IWB implementation. A study by Leong and Rasli (2014) also supported this assumption, and thus it is possible to conclude that IWB technology is well-perceived by males and females alike; however, variations are notable regarding how different genders use this technology.

Use of IWBs in Saudi Arabian Schools

Alghamdi (2015) confirms that smartboards and IWBs are already widely used in Saudi Arabian schools. They have made it possible for schools to transition from the traditional way of delivering course material to adopting modern and innovative teaching approaches. For example, IWBs have played a leading role in promoting English learning in the region (Alghamdi, 2015). Both students and teachers view IWBs as an effective way of facilitating quality education in the country. As in any other country, IWB utilization in Saudi Arabia has improved student’s performance by guaranteeing the quality of information and content fed to students (Alghamdi, 2015).

However, it is important to note that the creativity and skills of teachers are a primary determinant of how effective IWBs contribute to the learning process. Even though the adoption and utilization of IWBs are not complete in Saudi Arabia, a good number of schools are utilizing them (Al Mulhim, 2014). This section provides the researcher the foundation to collect primary data to understand the real issues directly or indirectly affecting the extensive implementation and utilization of IWBs in primary education in Hail City, Saudi Arabia.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

Al Arabiya. (2016). More than a third of the Saudi budget goes to education, health, and development. Web.

Albugami, S., and Ahmed, V. (2015). Success factors for ICT implementation in Saudi secondary schools: From the perspective of ICT directors, headteachers, teachers, and Students. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology, 11(1), 36–54.

Alenezi. A. (2015). Influences of the Mandated Presence of ICT in Saudi Arabia Secondary Schools. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 5(8), 638–644.

Alenezi, A. (2017). Technology leadership in Saudi schools. Education and Information Technologies, 22(3), 1121-1132.

Al-Ghaith, W.A., Sanzogni, L., and Sandhu, K. (2010). “Factors influencing the adoption and usage of online services in Saudi Arabia”, Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, 40(1), 1–32.

Alghamdi, A. & Higgins, S. (2015). Investigating how teachers in primary schools in Saudi Arabia were trained to use interactive whiteboards and what their training needs were. International Journal of Technical Research and Applications, Special Issue 30, 1–10.

Alghamdi, A. (2015). An Investigation of Saudi Teachers’ Attitudes towards IWBs and their Use for Teaching and Learning in Yanbu Primary Schools in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Arts and Sciences, 8(6), 539–554.

Almalki, G., & Williams, N. (2012). A strategy to improve the usage of ICT in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia primary school. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 3(10), 42–49.

Al Mulhim, E. (2014). The Barriers to the Use of ICT in Teaching in Saudi Arabia: A Review of Literature. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 2 (6), 487–493.

Alsied, S. M., & Pathan, M. M. (2013). The use of computer technology in the EFL classroom: Advantages and implications. International Journal of English Language and Translation Studies, 1(1), 61–71.

Amoudi1, K., and Sulaymani, O. (2014). The integration of educational technology in girls’ classrooms in Saudi Arabia. European Journal of Training and Development Studies, 1 (2),14–19.

Bakadam, E., & Asiri, M. J. S. (2012). Teachers’ perceptions regarding the benefits of using the interactive whiteboard (IWB): The case of a Saudi intermediate school. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 64, 179–185. Web.

Beauchamp, G. (2004). Teacher use of the interactive whiteboard in primary schools: Towards an effective transition framework. Technology, Pedagogy, and Education, 13(3), 327-348.

Beijaard, D., Verloop, N., & Vermunt, J. D. (2000). Teachers’ perceptions of professional identity: An exploratory study from a personal knowledge perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(7), 749-764.

BETCA (2003). What the research says about interactive whiteboards. British Educational Communications and Technology Agency. Web.

Celik, S. (2012). Competency levels of teachers in using interactive whiteboards. Contemporary Educational Technology, 3(2), 115–129.Bingimlas, K. A. (2009). “Barriers to the successful integration of ICT in teaching and learning environments”, a review of the literature. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education, 5(3), 235–245.

Countrystudies. (2018). Saudi Arabia – EDUCATION. Web.

De Vita, M., Verschaffel, L., & Elen, J. (2014). Interactive whiteboards in mathematics teaching: A literature review. Education Research International, 1–16.

DiGregorio, P., & Sobel-Lojeski, K. (2010). The effects of interactive whiteboards (IWBs) on student performance and learning: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 38(3), 255–312. Web.

Farooq, M. U., & Javid, C. Z. (2012). The attitude of Students towards E-learning: A Study of English Language Learners at Taif University English Language Centre. NUML Journal of Critical Inquiry, 10(2), 17–28.

Feteha, A. (2017). Key Figures in Saudi Arabia’s 2018 Budget, 2017 Fiscal Data. Web.

Firmin, M., & Genesi, D. (2013). History and implementation of classroom technology. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, 1603–1617.

Gray, C. (2010). Meeting teachers’ real needs: New tools in the secondary modern foreign languages classroom. In M. Thomas and E. C. Schmid (Eds.), Interactive whiteboards for education: Theory, research and practice (pp. 69–85). New York, NY: IGI Global.

Higgins, S., Beauchamp, G., & Miller, D. (2007). Reviewing the literature on interactive whiteboards. Learning, Media and Technology, 32(3), 213-225.

Hockly, N. (2013). Interactive whiteboards. ELT Journal, 67(3), 354–358. Web.

Huang, Y. M., Liang, T. H., & Chiu, C. H. (2013). Gender differences in the reading of e-books: Investigating children’s attitudes, reading behaviors and outcomes. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 16(4).

Isman, A., Abanmy, F. A., Hussein, H. B., & Al Saadany, M. A. (2012). Saudi secondary school teachers attitudes’ towards using interactive whiteboard in classrooms. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 11(3), 286–296.

Jang, S. J., & Tsai, M. F. (2012). Reasons for using or not using interactive whiteboards: Perspectives of Taiwanese elementary mathematics and science teachers. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28(8).

Kershner, R., Mercer, N., Warwick, P., & Kleine, J. S. (2010). Can the interactive whiteboard support young children’s collaborative communication and thinking in classroom science activities?. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 5(4), 359–383. Web.

Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2009). “What is technological pedagogical content knowledge?” Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 9(1), 60–70.

Lai, H. J. (2010). Secondary school teachers’ perceptions of interactive whiteboard training workshops: A case study from Taiwan. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(4).

Leong, C. T., & Rasli, A. (2014). The Relationship between innovative work behavior on work role performance: An empirical study. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 129, 592-600.

Ministry of Finance. (2018). Budget Statement Fiscal Year 2018. Web.

Oyaid, A. (2009). “Education policy in Saudi Arabia and its relation to secondary school teachers’ ICT use, perceptions, and views of the future of ICT in education”. Doctoral of philosophy PhD Thesis, University of Exeter.

Öz, H. (2014). Teachers’ and students’ perceptions of interactive whiteboards in the English as a foreign language classroom. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 13(3), 156-177.

Passey, D. (2010). Technology enhancing learning: Analysing uses of information and communication technologies by primary and secondary school pupils within learning frameworks. The Curriculum Journal, 17(2), 139–166.

Saudiarabiaeducation.info. (2018). Education Profile of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia Education System. Web.

Schmid, E. C. (2010). Developing competencies for using the interactive whiteboard to implement communicative language teaching in the English as a Foreign Language classroom. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 19(2), 159–172. Web.

Shen, C. C., & Chuang, H. M. (2010). Exploring Users’ Attitudes and Intention toward the Interactive Whiteboard Technology Environment. International Review on Computer and Software (I.RE.CO.S), 205.

Tezci, E. (2009). “Teachers’ effect on ICT use in education: The turkey sample”. (Elsevier)Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 1(1), 1285–1294.

Thomas, M., & Schmid, E. C. (Eds.) (2010). Interactive Whiteboards for Education: Theory, Research and Practice. New York, NY: IGI Global. Web.

Tondeur, J., Keer, H., Braak, J. & Valcke, M. (2008). “ICT integration in the classroom: Challenging the potential of a school policy”. Computers & Education, 51(1), 212–223.

Türel, Y. K., & Johnson, T. E. (2012). Teachers’ Belief and Use of Interactive Whiteboards for Teaching and Learning. Educational Technology & Society, 15(1), 381–394.

Wong, E., S.C., S., Li, T.-H., Choi & Lee, T.-N. (2008). Insights into innovative classroom practices with ICT: Identifying the impetus for change. Educational Technology & Society, 11(1), 248–265.

Yang, J. Y., & Teng, Y. W. (2014). Perceptions of elementary school teachers and students using interactive whiteboards in English teaching and learning. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 25(1), 125–154.